In the world as it stands today, the pro-immigration/pro-immigrant crowd has aligned itself with the anti-discrimination/anti-racist crowd. There is clear common cause in more ways than one:

- The anti-racist/anti-discrimination positions seek to end discrimination on the basis of criteria such as race. The pro-immigration crowd, and in particular the open borders crowd, seeks to end (government-enforced) discrimination on the basis of birthplace and nationality.

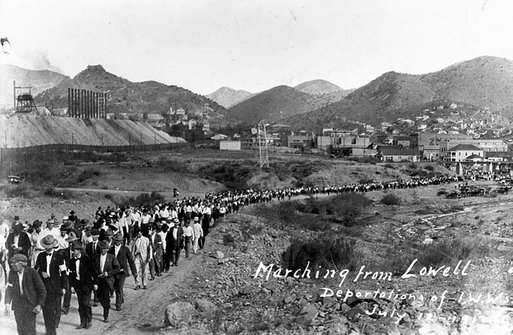

- Historically, many immigration laws (starting with the Chinese Exclusion Act, the beginning of the modern era of immigration restrictions) were justified on racial/ethnic grounds.

- Even today, immigration laws, as well as their enforcement, tend to have disparate impact by race and ethnicity, even without any of the enforcing actors necessarily having racist motives.

Many open borders advocates accept or even deploy these arguments, and this helps establish common ground with many mainstream pro-immigration people. However, there is another interesting strain of thought in the open borders movement, stemming from its ideologically libertarian-leaning wing, that affirms the importance of allowing private discrimination. The idea is that freedom of association is of intrinsic value, and forbidding private discrimination interferes with this right. Interestingly, from this perspective, the quest for open borders (specifically framed in terms of the right to migrate and right to invite) and the quest for allowing private discrimination have affinity: both can be justified based on the importance of freedom of association (I discuss this at greater length a little further down in the post, before getting into the implications for open borders).

Now, to be clear, all three positions discussed (open borders, moral opposition to racism and discrimination, and the importance of letting private discrimination be legal) are mutually consistent. Nonetheless, the position that private discrimination should be legal and the view of discimination as morally problematic are connotatively in tension, particularly once we get outside the circle of people with hardcore libertarian beliefs.

An interesting twist to this triad of views was introduced by my co-blogger Nathan Smith, in his blog posts No Irish Need Apply and Private discrimination against immigrants is morally fine, and should be legal and later in a post on the Open Borders Action Group on Facebook. Nathan argued that allowing private discrimination might be a way to appease people concerned about their ability to avoid (particular types of) immigrants that we’d see more of under open borders. He therefore proposed (open borders + allow private discrimination) as a package deal (in the language of this post of mine, this would qualify as a complementary policy to open borders, though if the legalization of discrimination was restricted to discrimination against immigrants, it would qualify as a keyhole solution in that jargon). In this post, I’ll dissect different arguments of the sort Nathan has articulated and alluded to, and explain my reasons for skepticism of them.

Some background on discrimination

In many contemporary polities, particularly in the United States, opposition to discrimination (particularly along certain dimensions such as race and ethnicity) has attained a moral primacy, at least rhetorically. Philosophically, this has puzzled me. Consider a recent topical category: when incidents of police brutality are reported, there is often significant emphasis on whether the police behavior was discriminatory on the basis of race, often even more so than the question of how justified or excessive the police action was. Racial discrimination was a key theme in discussion of the recent 2015 Texas pool party incident, even though the officer in question had, to begin with, arrested a white girl (this was not part of the viral video, but happened before the video commenced). This led to the weird situation where the officer sought to defend his behavior from charges of racism by pointing out that he had arrested a white girl, even though that arrest too was unjustified.

The emphasis on discrimination can be counterproductive because it can lead to the rejection of Pareto-improving solutions that are discriminatory. In the context of migration, for instance, the expansion of migration quotas or relaxation of migration barriers for people of certain classes or nationalities increases discrimination between potential migrants, even if, overall, it expands human freedom. Reasons of this sort are why those I know who are more hardcore libertarians, as well as more utility-oriented or efficiency-oriented, tend to not give primacy to narratives focused on discrimination. My point here isn’t that hardcore libertarians or utilitarians support discrimination, but rather, that they don’t treat discrimination as a key yardstick by which to judge the morality or desirability of actions.

However, I believe that the focus on discrimination in public discourse is not as irrational or ungrounded as it might appear from a purely philosophical standpoint. I think there are a few reasons for this:

- It feels awful to be discriminated against, and more generally to be in an environment where you’re constantly wondering whether other people’s behavior toward you is influenced by prejudice: Obviously, in cases where the people who might be discriminating against you are people with a huge amount of authority over you (such as police officers, consular officers, or judges) the feeling is terrible. The fear that they are prejudiced against you, whether justified or not, adds insult to any injury they may inflict on you. But even when the other actors involved have little power over you, the fear that their behavior towards you is based on discrimination for reasons you cannot control, can be demoralizing. My co-blogger Nathan has pointed out in his posts the standard economic wisdom that, even if many people discriminate against a particular race or ethnicity, the material harm to members of that race or ethnicity is minimal as long as there are enough people who don’t discriminate. But despite this small material harm, the psychological damage, even if not debilitating, is nothing to be laughed at. If you know that 20% of restaurants will refuse to serve you due to your race, or that 10% of police officers will stop you for absolutely no reason other than your race and subject you to a time-wasting and humiliating strip search, this detracts from your ability to partake of public life with dignity.

- In addition to the direct effects of discrimination against those parties being discriminated against (as well as others who my incorrectly believe themselves to be the victims of discrimination) there are also ripple effects on economic and social activity. Some of it might get canceled because of the impediments and inefficiencies created by discrimination. A business might choose not to hire the best employee because of discrimination by its customers against the employee’s race/ethnicity. A group of people might decide not to go to a restaurant or cinema hall that they would have enjoyed, because one member of the group would be barred from the place on account of race or ethnicity.

- Discrimination, insofar as it largely targets people who lack the relevant kind of power (which may be political, economic, or social) means that the people with the power to change policies are often insulated from the consequences. If police officers behave in humiliating ways only when interacting with people who look young and poor, then those who run city governments and police forces, who tend to be older and richer, may never experience the brunt of humiliating policing. Since these individuals don’t get firsthand experience in the implementation of the policies, they have little incentive to change them. A non-discriminatory and egalitarian approach makes sure that those creating and influencing policies eat their own dog food.

The libertarian perspective, that I largely endorse (although this isn’t an issue that I’m passionate enough about to generally argue in favor of) acknowledges these points, but balances them against these considerations (note that while I try to articulate below a libertarianish view, many libertarians don’t subscribe to it, and many non-libertarians do):

- In the context of coercive state actors, the libertarian perspective seeks to reduce the coercive, discretionary power that lies with these actors in the first place. The less coercive power these actors have, and the less discretionary leeway the actors have, the less scope there is for them to discriminate in invidious ways, while also reducing abuse of these powers at large. In the context of police abuse, reduced police authority to arbitrarily stop and detain people, the legalization of victimless crimes, and an end to Broken Windows policing-like approaches, reduce the scope for those in authority to harass people at large, and also to do so in a discriminatory fashion.

- In the context of private discriminators, the libertarian position acknowledges that those discriminated against have experiences ranging from unpleasant to traumatizing. However, the libertarian position still gives importance to freedom of association, even when it leads to bad consequences for others, as long as it does not directly violate their rights. Libertarians also point out that forbidding discrimination can have bad effects not only on those engaged in the odious type of discrimination that is the target of the law but in other, more innocuous, forms of discrimination.

James Joyner articulates the second point well:

Paul’s views are identical to those I held when studying Constitutional Law as an undergrad and not all that far removed from my current position. There’s no question in my mind that private individuals have a right to freely associate, that telling owners of private businesses whom they must serve amounts to an unconstitutional taking, and that it’s none of the Federal government’s business, anyway. Further, in the context of 2010 America, I absolutely think that business owners ought to be able to serve whomever they damned well please — whether it’s a bar owner wishing to cater to smokers, a racist wanting to exclude blacks, or a member of a subculture wishing to carve out a place for members of said subculture to freely associate with only their kind out of purely benign purposes.

The problem, circa 1964, was that there really was not right to freely associate in this manner in much of the country. Even once state-mandated segregation was ended, the community put enormous pressure on business owners to maintain the policy. That meant that, say, a hotel owner who wished to rent rooms without regard to color really weren’t free to do so. More importantly, it meant that, say, a black traveling salesman couldn’t easily conduct his business without an in-depth knowledge of which hotels, restaurants, and other establishments catered to blacks. Otherwise, his life would be inordinately frustrating and, quite possibly, dangerous.

In such an environment, the discrimination is institutionalized and directly affecting interstate commerce. It was therefore not unreasonable for the Federal government to step in using their broad powers under the 14th Amendment. I’m still not sure parts of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 (especially the issue in question here) or the Voting Rights Act of 1965 (especially treating individual states differently from others) are strictly Constitutional. But they were necessary and proper in the context of the times.

The problem that libertarians and strict Constitutionalists have, however, is that precedents set under extreme and outrageous conditions are often applied to routine and merely inconvenient ones. (Or, as the old adage goes, “Hard cases make bad law.”) Once someone’s private business is transformed by fiat into a “public accommodation,” there’s precious little limit to what government can do with it. Requiring private individuals to treat black people with a modicum of human dignity is one thing and dictating what kind of oil they can cook their French fries in or how much salt they can put on them is quite another. But, in principle, they’re not much different.

Piyo draws parallels between freedom of association and freedom of speech, noting the irrationality in how people unequivocally defend freedom of speech while treating defense of freedom of association as anathema:

I confess that I’ve always found this controversy rather puzzling. Consider the following two propositions:

1. A citizen should be allowed to promote white supremacy and racial segregation in a personal blog, in a book, in flyers that he hands out on street corners, to his children, or among his neighbors at weekly meetings at his home

2. A citizen should be allowed to refuse service to non-whites at his store

I find it incredibly odd that believing #1 is considered normal, enlightened, and mainstream, while believing #2 is considered crazy at best and mega-, KKK/slave-owning/Django-level racist at worst. In fact, judging from the controversy over Paul’s stance, I think many or most people believe that it is totally impossible to believe #2 without being racist. Don’t get me wrong; I can easily imagine a reasonable set of beliefs that would lead a person to agree with #1 and disagree with #2. However, I can’t imagine how everyone seems to believe the following

3. #1 is obviously true and everyone should believe so, and #2 is obviously false, and anyone who disagrees is either evil or being willfully ignorant.

I can think of two reasons why a person might confidently believe that #2 is false. Unfortunately, neither of these theories explain the widespread belief in #3.

[…]

More reasonable, I think, is to conclude that almost nobody’s attitude toward #1 or #2 is based on any kind of ratiocination. Through a combination of historical accident and the all-powerful status quo bias, endorsing #1 has become a way to express to others that you, too, value freedom, and rejecting #2 has become a way of expressing that you, too, think racism is bad. If you hold these beliefs, then you’re part of our “group”.

For more discussion of the libertarian perspective on discrimination and some pushback to it, see this Cato Unbound discussion of the subject.

UPDATE: In an email, reproduced with permission, Nathan responds to my point about it being awful to be discriminated against:

The place where I had least sympathy with the argument was where you talked about being discriminated against and how horrible it feels. I can see why it would be pretty bad to be in the position of African Americans before the civil rights movement, when widespread discrimination was enforced by a sinister conspiracy of the law with the domestic terrorists of the KKK, and when most of the population discriminated against you so that your opportunities to flourish in life were severely limited by discrimination on every side, and when discrimination did seem to be motivated by hatred. But I can’t see how it would be so bad to suffer from occasional statistical discrimination not motivated by hatred. Suppose a taxi cab driver were to tell me, “Sorry, it’s nothing personal, but I don’t pick up young men in this part of town, because young men commit most of the crime, and I only have to pick up the wrong fare once, and my wife’s a widow.” If I needed the cab that would be inconvenient of course, but I wouldn’t feel profoundly insulted. I’d feel sorry for the guy for being in such a risky job and earnestly hope and pray for his safety. The notion that it’s an intolerable indignity to be discriminated against, but it’s NOT an intolerable indignity to be forced by the government and its anti-discrimination laws to open one’s home or business to people one doesn’t like or approve of, seems utterly insane. If it feels so horrible to be discriminated against today, even when it causes negligible inconvenience, I suspect that’s either because we’ve been brainwashed into thinking discrimination is the root of all evil, or because what certain groups (LGBT especially) really want is to coerce people to APPROVE of them, a common motive among those who have power. Discrimination against LGBT is an expression of disapproval and as such must be suppressed.

Bryan Caplan’s weighing of the relative importance of immigration restrictions and anti-discrimination law

In a blog post titled Association, Exclusion, Liberty, and the Status Quo, Bryan Caplan, who supports both open borders and an end to anti-discrimination laws, compared the importance of the issues:

I don’t deny that laws against exclusion occasionally have important effects. But their main effect in the modern U.S. economy isn’t to reduce exclusion, but to pressure businesses to either overpay or avoid hiring workers who can easily sue for “discrimination.”

Now consider regulations on the freedom of association. Many are marginal, too. Not much would change if you legalized gay marriage or polygamy; they’re just niche markets. But one class of regulations has a massive effect: immigration laws. Indeed, they probably have a bigger effect than all other regulations combined.

It’s simple. Billions of people around the world live on a few dollars a day or less. Under open borders, tens of millions of them would migrate to the U.S. every year. Remember: Even if you’re an illiterate peasant who doesn’t understand interbank transfers from Bangladesh, credit markets and/or employers would be happy to front the money for airfare.

This immigration flow wouldn’t stabilize until real estate prices massively increased and low-skilled wages drastically declined. The U.S. population could easily increase by 50% in a decade. New cities would blanket the country. The level of output would skyrocket – and its composition would rapidly change, too. Whether you love this vision or hate it, you can’t deny that free association would radically and rapidly reshape the face of America.

I’m as supportive of the right to exclude as anyone. But current restrictions on this right are pretty minor. There are plenty of ways for markets to engineer exclusion, and there’s not much demand for greater stringency. In contrast, restrictions on the right to associate are massive, and there is enormous pent-up demand to migrate. Hundreds of millions of people want to move here, landlords want to rent to them, employers want to hire them – but the law won’t allow it.

Contrary to my conservative friend, then, libertarians aren’t the ones with a blind spot. He is. While restrictions on exclusion are occasionally irksome, they rarely ruin lives. Immigration laws, in contrast, usually condemn their victims to life – and often early death – in the Third World. Libertarians rightly emphasize the freedom to associate, because the status quo’s restrictions on exclusion are minor and mild – and the status quo’s restrictions on association are massive and monstrous.

A closer look at the link between legalizing private discrimination and open borders

Here’s Nathan’s Open Borders Action Group Facebook post (which is the most recent formulation of his view, though his previous blog posts are also worth reading):

Would it be useful to the open borders movement to roll back anti-discrimination laws? Consider the following argument, made to a nativist: “Hey, if YOU don’t like immigrants, fine, you don’t have to do associate with them. But stop interfering with those of us who DO want to associate with them.” This argument needs refining, but I think some form of it could have a lot of force if it weren’t for “public accommodation” laws that force all residents of the US to integrate. As long as so-called “anti-discrimination” laws are in place (misnamed of course since for now discrimination against undocumented immigrants is not only allowed but mandated), this argument doesn’t work very well, since the government might force you to hire immigrants. In effect, the current policy choice is whether discrimination against the foreign-born should be mandatory or illegal, whereas of course, the sensible middle way is to make it voluntary. But to get to it, we’d have to legalize discrimination. Now, I’m hopeful that the attack on religious freedom by the LGBT lobby will backfire and lead to a general revival of tolerance and freedom of association, as the absurdity of having the government force people to bake a cake for a “wedding” they don’t morally approve of, forces us to revisit some deep ethical mistakes we’ve been making for the past generation. If this happens, would it help the open borders cause?

There are several different flavors of the argument, that I’ll list before opining:

- If private discrimination were legalized first, the open borders position would be more philosophically defensible than it is now.

- The (open borders + allow private discrimination) package deal is more philosophically defensible than mere opening of the borders, while private discrimination continues to remain illegal.

- If private discrimination were legalized first, the open borders position would be more practically feasible than it is now.

- The (open borders + allow private discrimination) package deal is more practically feasible than mere opening of the borders, while private discrimination continues to remain illegal.

I agree with the view (1): the freedom-based arguments for open borders make more sense in a world where people are freer to not associate with immigrants if they so choose, and the other arguments are largely unaffected. I think the change to the strength of open borders isn’t too huge, largely because of the reasons that Caplan articulated in his post that I quoted above.

I also agree (weakly) with (2): bundling open borders with a broader expansion of the freedom to associate (and exclude) would be more philosophically defensible than merely opening the borders. However, unlike (1), (2) only applies from the perspective of the libertarian case. Those whose reasons for supporting open borders are more egalitarian might well disagree with (2). If you agree with Caplan’s post, however, the effect size either way is relatively small.

This leaves (3) and (4), the questions of practical feasibility. Regarding (3), I believe that there are good arguments on both sides, and I think ultimately it will depend on the details of the societal changes that lead to a relaxation or termination of anti-discrimination laws in the first place. However, I am very skeptical of (4). I don’t think an (open borders + allow private discrimination) package deal is more practically feasible. I don’t think those keen to see open borders become a reality should attempt to draft such a deal or push for it. I think the main benefit of discussing such a combination, apart from the philosophical clarity it offers, is that if somehow the circumstances changed and such a deal became the main way to proceed with open borders, then our thoughts on the issue would be clearly fleshed out.

I’ll begin by elaborating on (3). Why might anti-discrimination laws, such as those surrounding public accommodations in the United States, be repealed or relaxed? I believe there are three broad categories of reasons:

- The moral argument for the freedom to associate and exclude gains widespread acceptance.

- Efficiency-based arguments against such laws take force. This could be helped by public outrage or disgust at what is perceived as spurious use of anti-discrimination laws.

- People interested in discrimination on the basis of race, ethnicity, or some other criterion push for the changes, and their views become influential among the public or among policymakers.

I think that, if (1) is the prime mover for the change in laws, there is a decent chance that public opinion would have also shifted more in favor of freer migration, and Nathan’s logic might then accentuate the effect. In the case of (2), public opinion may remain largely unchanged on migration, but Nathan’s logic might help tip it slightly more in favor of free migration. However, in the case of (3), I think it’s quite likely that public opinion will be more hostile to immigration than before. Even if Nathan’s logic serves to counter that somewhat, I think the net effect would still be in a significantly restrictionist direction. I think that, given what we know today about public opinion, in the highly unlikely event that anti-discrimination law is repealed, this is more likely to happen because of reason (3) than because of the other two reasons (though I expect the overall chances of such repeal as pretty low, so this is merely an academic observation).

Finally, as for (4), the reason I’m skeptical is that, in the present day, there isn’t really a large coalition (outside of hardcore libertarians and efficiency-oriented folks) who support the repeal of anti-discrimination law out of a love of true freedom, as opposed to a desire to facilitate discrimination per se. And, outside of libertarians, people have trouble separating private action from government-enforced action. So, this bundle wouldn’t really appeal to many people, and in addition, means that open borders advocates might lose the support of the broader, mainstream, pro-immigrant people.

John Lee offers a detailed response to Nathan’s Facebook post that I largely endorse:

While this is an interesting idea, I don’t see how you would be able to build a political coalition around both liberalising migration and repealing anti-discrimination laws. I’m skeptical that xenophobes would tolerate having more immigrants around if they were allowed to discriminate against them; I mean, I’m persuadable that their opposition to open borders might diminish somewhat, but I don’t think it’d go away.

A lot of the costs that people complain about as far as integration goes have to do with things that anti-discrimination law doesn’t really meaningfully impact: pressing 1 for English, overhearing funny languages in public, not being able to ask for directions in a strange neighbourhood where nobody looks like you or can speak your own language, etc. Repealing anti-discrimination laws solves for essentially none of these xenophobic complaints.

(Technically repealing anti-discrimination law might partially solve for the “press 1” complaint since that’s to some degree a policy caused by public accommodation laws, but in a free market operating in a diverse society, a lot of companies would naturally provide multilingual servicing anyway. Malaysia and Singapore don’t have meaningful anti-discrimination laws but multilingual servicing is omnipresent in the market because of how diverse their societies are.)

As an aside, this idea is not even applicable outside the Western world; to Christopher’s point, I don’t think this is a “reform” that can be bundled into anything in Asia or Africa, perhaps even Latin America, because most non-Western countries don’t have much anti-discrimination laws to speak of. Speaking from my experience, it’s common to see classified ads in Malaysia and Singapore specifying that they won’t accept job candidates or tenants of particular sexes or genders. (Recently some companies have tried to capitalise on public distaste for these kinds of ads by running ads which explicitly state that they don’t discriminate.)

Now to be sure, introduction of new anti-discrimination laws to these non-Western societies would spur blowback, and I would generally advise against trying to bundle liberal immigration reforms with new anti-discrimination laws in these societies. But that’s separate from trying to bundle liberal immigration reforms w/ anti-discrimination legislation repeals in societies that already have these laws.

He later writes:

[T]he reality of mood affiliation makes me skeptical that one could build a coherent political coalition aligned on just these two things without that coalition consisting pretty much entirely of libertarians.

A couple of my comments in the thread are also relevant, and I quote them below:

I don’t think that the repeal of such legislation would make the world more friendly to open borders: your argument for would be balanced by an argument against, namely that the legitimization of discrimination as morally acceptable might make people more forthright about using it as a basis for public policy (given that people generally have trouble keeping private preferences out of the domain of government-enforced public policy).

“But I don’t think there’s any point in pitching an advocacy strategy to such numbskulls. If mankind is as stupid as that, we won’t make any headway. Fortunately, mankind does sometimes exhibit a capacity to think such moderately subtle thoughts as, “Discrimination against the foreign-born should be legal for private individuals but not be mandated by law.””

Most people would be able to understand this idea if they tried hard enough, but people aren’t generally inclined to put in a lot of effort into evaluating political positions. In general, I would expect that a move that legitimizes private discrimination would be seen (by the general public) as a signal that discrimination is more acceptable both in private and in public policy. At the same time, the people you are most trying to appease with such a policy are likely to not stop at private discrimination anyway.

Conclusion

Discrimination is hurtful, both directly when it’s done, and indirectly because of the fear and inefficiency it creates in society. However, freedom of association and exclusion are important values. Libertarian-leaning people (including myself) think that under most circumstances, private discrimination should remain legal. There may be exceptional circumstances where the harm from discrimination is severe enough to infringe on people’s freedom of association and exclusion. Some people sympathetic to the overall libertarian argument have argued that the post-1964 Jim Crow South presented such an exceptional circumstance, but the present day is not similarly exceptional, so legalizing private discrimination in the modern era is okay.

From a libertarian philosophical perspective, that I largely endorse, repealing some anti-discrimination laws make the case for open borders stronger, insofar as open borders will mean dealing more with a wider range of people. However, as a practical matter, I don’t think it makes sense to try to push for a deal packaging open borders with such repeal. If such a deal emerged as the most feasible way to push for more liberal migration, it might be worth supporting.

Related reading

These links are offered in addition to the numerous inline links in the post.

- Are immigrant rights activists friends of open borders? by Vipul Naik, Open Borders: The Case, October 25, 2012.

- Discrimination and the semi-open border by Paul Crider, Open Borders: The Case, July 4, 2013.

- Wage discrimination’s elephant in the room by John Lee, Open Borders: The Case, October 22, 2012.