This post was originally published on the Cato-at-Liberty blog here and is republished with the permission of the author.

On Friday, Ross Eisenbrey of the Economic Policy Institute wrote an op-ed in the New York Times titled “America’s Genius Glut,” in which he argued that highly-skilled immigrants make highly skilled Americans poorer.

A common way for highly-skilled immigrants to enter the United States is on the H-1B temporary worker visa. 58 percent of workers who received their H-1B in 2011 had either a masters, professional, or doctorate degree. The unemployment rate for all workers in America with a college degree or greater in January 2013 is 3.7 percent, lower than the 4 percent average unemployment rate for that educational cohort in 2012. That unemployment rate is also the lowest of all the educational cohorts recorded.

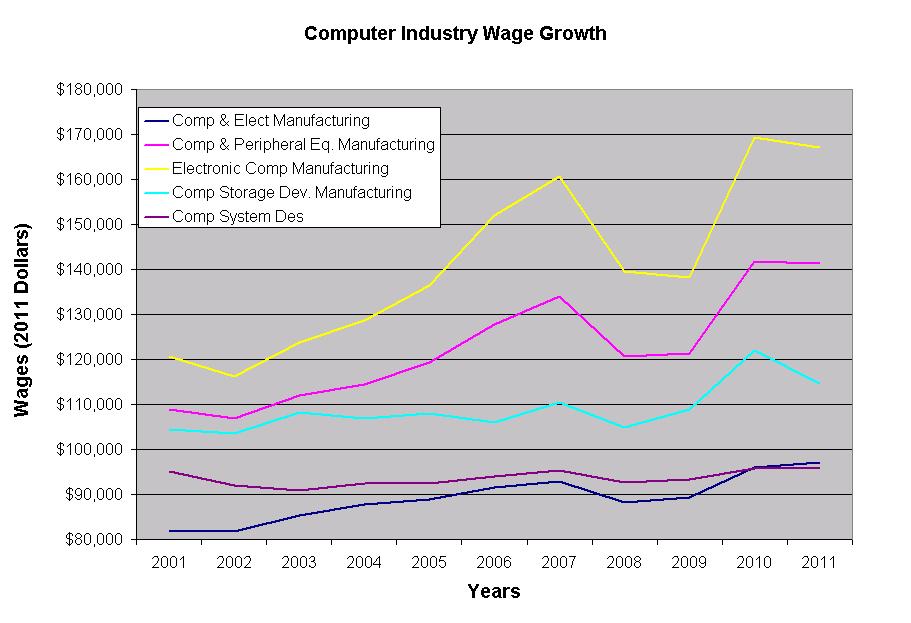

Just over half of all H-1B workers are employed in the computer industry. There is a 3.9 percent unemployment rate for computer and mathematical occupations in January 2013, and an unemployment rate of 3.8 percent for all professional and related occupations. For selected computer-related occupations from the Bureau of Labor Statistics’ “Quarterly Census of Employment and Wages,” real wage growth from 2001 to 2011 has been fairly steady:

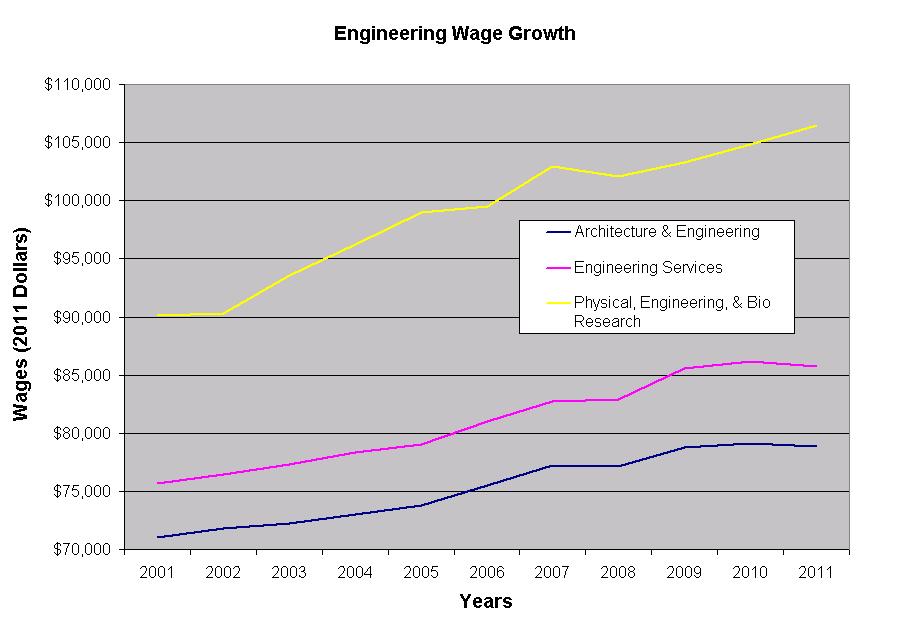

11 percent of H-1B visas go to engineers and architects but wage growth in those occupations has been fairly steady too:

Mr. Eisenbrey concludes that those rising incomes would rise faster if there were fewer highly-skilled immigrants.

The unemployment rates for engineers and computer professionals are low but not as low as they used to be. There are a whole host of factors explaining that, but highly-skilled immigration is not likely to be one.

Mr. Eisenbrey also claims that American firms hire H-1B visa workers because they are paid lower wages. Complying with certain regulations prior to hiring an H-1B can cost a firm $10,000, filing and other fees can cost additional thousands of dollars, and legal fees can be steep. The cost of hiring H-1Bs is high.

Contradicting Mr. Eisenbrey’s story about H-1Bs lowering American wages, IT workers on H-1Bs actually earn more than similarly skilled Americans. According to survey data, H-1B workers are more willing to work long hours and relocate to a job, making them more productive and raising their wages. Additionally, H-1B engineers are paid $5,000 more a year than American born engineers. If the goal of employers was to hire cheaper workers through the H-1B visa, they’re going about it in an odd way. The high regulatory costs and wages of employing H-1B workers incentivizes firms to hire foreign workers when they are expanding and can’t find American workers fast enough.

Mr. Eisenbrey’s doesn’t touch on other characteristics of highly-skilled immigrants such as their high rates of entrepreneurship, inventiveness, or skill complementarity. If the New York Times chooses not to run one of my letters to the editor about those topics, I will be writing about them in the upcoming weeks.

There is a 3.9 percent unemployment rate for computer and mathematical occupations in January 2013, and an unemployment rate of 3.8 percent for all professional and related occupations.

That’s ridiculous. The unemployed aren’t counted if they get a job doing something else. The unemployment rate for lawyers is 15-20%, but the government somehow figures it at 2 or 3%.

Reply

Nor are they counted if they’ve been unemployed for more than 6 months.

Reply

Contradicting Mr. Eisenbrey’s story about H-1Bs lowering American wages, IT workers on H-1Bs actually earn more than similarly skilled Americans.

“Contradicting”? I think you mean, “corroborating”. Obviously, if Americans got the jobs the H-1B’s get, the Americans would earn more than they’re earning now.

Reply

Ben,

Thanks for your insightful comment. If I understand you correctly, your argument is that by definition, an increase in the supply of labor drives down wages. There are good prima facie theoretical reasons to have a strong prior in favor of this. There may be exceptions, based both on skill complementarities between workers and on minimum efficient scale for certain types of industries — we’ve discussed these at our page on the subject, and see also Nathan’s comment on this post. But one might well take a stand that strong evidence is needed to overcome the prior of an increased supply of labor driving down wages, and that the evidence cited by Alex does not qualify for that strong claim (though his last para, where he references skill complementarity, suggests he might offer more evidence of that sort in the future).

What Alex was critiquing here was not the general claim of non-immigrant guest workers driving down natives’ wages, but the more specific mechanism proposed by Eisenbrey for this: that they do so by offering their own services at substantially lower pay and/or are exploited by employers. Eisenbrey, in his article, argued that H1B workers earn less than comparable native Americans. Alex is citing data to suggest the opposite. As with all data, there are problems with defining “similarly skilled” — but if you believe Alex’s data, then they contradict Eisenbrey’s specific story. That was the purpose of Alex’s critique as I understand it.

Setting aside Eisenbrey’s story for the moment, if your belief that guest workers drive down native wages is based on theoretical economic reasoning (as you suggest), then that belief would be stable both under learning that guest workers earn higher than native workers and under learning that guest workers earn lower than native workers. Either empirical observation is consistent with a wage suppression effect. But that does not mean that evidence for either of the two cases corroborates your story. Your story is agnostic to whether guest workers are earning more or less than natives at any given point in time — either is consistent with natives earning less than they would under the counterfactual. So, in this case, my view is that the word “corroborates” oversells the case for the evidence bearing out a story since you’d anyway decided (for generally sound economic reasons) that the story is true.

Reply

I tend to think that the availability of H1-B visas probably does lower the wages of Americans with certain kinds of technical skills, which theory would predict. In general, increase the supply of something, and its price falls. That’s the law of demand. Having said that, there may be reasons that this rule does NOT apply to H1-B visaholders, because some of them may work in sectors with strong O-ring effects (see Jones: http://www.economicdynamics.org/meetpapers/2008/paper_674.pdf) and/or sectors involved in idea generation, which doesn’t run up against the same kinds of scarcity.

Still, what I find really odd is that anyone should regard protecting the wages of highly-skilled American workers from foreign competition as a policy priority. As you observe, wage growth for these workers is pretty robust, but I’d stress even more that the LEVELS of wages for these people are quite high, well above the median. Most of us aren’t engineers; most of us are consumers of products that engineers make. More engineers, even, or rather especially, at lower wages, should be good for the non-engineer majority of the American people under almost any theory you could come up with. It would take considerable ingenuity even to suggest how it might be POSSIBLE that most American non-engineers would NOT benefit (at least economically) from the immigration of such people. And since non-engineers are a good deal poorer than engineers, on average, surely their interests should count at least as much as those of people competing with H1-B visaholders, even if we set aside the issue of the merits of freedom per se. And then there’s the concern of national power, if you’re into that kind of thing: H1-B visas allow America to grab a larger share of the world’s top-level technical expertise. Even if it were beyond dispute that engineers’ wages are undercut by competition from H1-B visaholders, it would be bizarre to regard that as a plausible motivation for restricting the supply. Unless you’re a lobbyist for an engineers’ union or something.

Reply

The Cato Institute, is a mouthpiece to advance the agenda of its benefactors, led by the Koch brothers. Their pay to play H-1b visa research, is biased, unfounded and cannot be defended by the facts from government audits of the H-1b program and pure propaganda.

Reply