Last month, I shared with the Open Borders Action Group an interesting Facebook post from Andy Craig, a Libertarian running for Congress in Wisconsin, pointing out the hypocrisy of many US presidential candidates promoting anti-immigrant policies:

Bobby Jindal, who wants to stop so-called anchor babies, was born four months after his parents arrived in the U.S. on temporary student visas.

Donald Trump, who has made actually deporting so-called anchor babies a centerpiece of his campaign, is the son of a woman from Scotland who was naturalized four years before he was born.

Bernie Sanders, who says allowing more immigrants is a Koch brothers plot to reduce wages, is the son of a Polish immigrant who arrived penniless in the United States to escape the Holocaust.

Ted Cruz and Marco Rubio have one and two parents, respectively, who were naturalized after their sons were born. Rick Santorum’s father was naturalized before Rick was born, when his own father brought him here fleeing Mussolini.

A nation of immigrants: where anybody’s child can grow up to run for President and campaign on pulling up the ladder behind them.

(One thing Craig forgot to mention: Trump’s grandfather Friedrich was an unaccompanied child migrant, who was later deported from Germany.)

Now, the hypocrisy these candidates embody is one thing. But something else stood out to me too: none of these candidates’ ancestors were referred to as “refugees,” even though many of them certainly were. For some reason, it’s better to label someone as an “immigrant” rather than “refugee.” But look at these stories:

- Bernie Sanders’s father fled the Holocaust

- Ted Cruz’s family fled the Castro regime in Cuba

- Marco Rubio’s family fled the same Castro regime

- Rick Santorum’s grandfather fled Italian fascism

Someone who moves across international borders owing to a fear of violence or political persecution is by definition a refugee. By this count, a substantial number of candidates for the US presidency are descendants of refugees!

It sounds strange to put it that way, because we are not used to thinking of refugees in that way. The way we normally think of people labeled as “refugees” is more similar to the thinking I saw in another posting on Facebook:

Refugees can’t be helped, regretfully. You can’t teach them anything, you can’t provide them all with housing, you can’t give them all jobs. Refugees are to remain [a] burden forever, and even their children won’t be able to integrate.

Well of course if you redefine “refugees” as “immigrants” you’ll have a mysterious shortage of refugee success stories. “Immigrant” has a successful ring to it; “refugee” does not. Self-reinforcingly, we think of successful people as “immigrants,” and the less successful ones who didn’t fare so well as “refugees.” We forget that even titans of business like Andy Grove, the co-founder of Intel, and George Soros, a self-made billionaire, are literally refugees.

(Of his early life, Grove has said: “By the time I was twenty, I had lived through a Hungarian Fascist dictatorship, German military occupation, the Nazis’ ‘Final Solution,’ the siege of Budapest by the Soviet Red Army, a period of chaotic democracy in the years immediately after the war, a variety of repressive Communist regimes, and a popular uprising that was put down at gunpoint… Some two hundred thousand Hungarians escaped to the West. I was one of them.” Soros’s biography on his website simply states: “Born in Budapest in 1930, he survived the Nazi occupation during World War II and fled communist-dominated Hungary in 1947 for England”.)

All that said, I don’t think the distinction between refugees and “economic migrants” are as important as they’re made out to be. Whether you’re fleeing persecution, escaping economic deprivation, or simply looking to live in a slightly better neighbourhood, I think the law ought to treat you exactly the same way when you show up at the border. All of these are perfectly valid reasons for someone to move.

To this end, I consider it morally suspect to insist economic migrants be deported but refugees be welcomed. Consider: millions of African Americans moved from the southern US to the north and west during the Great Migration in the first half of the 20th century. Some fled political persecution and racial discrimination. Others simply went looking for better jobs. But both were and are perfectly valid reasons to move.

(Sidenote: Republican presidential candidate and internationally-renowned neurosurgeon Ben Carson was born in Detroit to parents who fled the Jim Crow laws of Tennessee, participating in the Great Migration. If you’d like to count “internally-displaced people” as well, you can add another one to that list of presidential candidates descended from refugees.)

At the same time, I think it’s important, as long as the word “refugee” remains part of the English lexicon, to remember that “refugee” does not connote someone who is “to remain [a] burden forever”. People sometimes presume that refugees are tremendously harder to integrate into society or the economy because of their background. This may be true, but it’s simultaneously clear that whatever problems refugees may face, they don’t stand in the way of a refugee like George Soros becoming one of the 30 richest men in the world, or in the way of refugees’ descendants becoming the face of popular national campaigns against immigration.

Refugees, like any other kind of immigrant, are people. It is not a valid use of government authority to ban people from travelling somewhere simply because of where they were born. If government can prove that certain kinds of travel would have terrible consequences, of course government can prevent that sort of movement. Take infectious diseases for example: travel restrictions aimed at preventing the spread of dangerous diseases have to be blind to nationality if they are to operate effectively. Border officers don’t need to know or care about someone’s nationality to effectively prevent the spread of Ebola because any person, foreign or not, can carry Ebola.

Now while we’re talking about the effects of refugee movements: the Great Migration of people fleeing political oppression and economic deprivation in the American South was incredibly disruptive. In many cities, from New York to Philadelphia to Chicago to Seattle to San Francisco, over the span of a few decades, the black population grew 10 to 20 times over. Boston went from being 2% black in 1910 to 22% black in 1980. Adjusting to these inflows was not easy for the affected communities outside of the South. But these adjustment costs were neither disastrous, nor valid reasons to obstruct the legitimate aspirations of the Americans who moved in search of a better life.

That’s why I support open borders for all people — be they refugees fleeing oppression, economic migrants fleeing poverty, or even just middle-class professionals who dream of living in a different city. No country should allow its public institutions — like its border controls — to become the private property of xenophobic bigots. Yet, the modern refugee system has become a figleaf for border policies of bigotry. What basic morality asks of us and our laws is clear: justice demands that all people with legitimate aspirations be free to move across political borders, be they domestic or international.

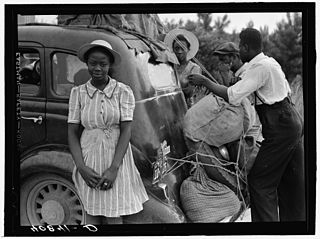

The photograph in the header of this post is of African American migrant workers from Florida bound for New Jersey in 1940. Courtesy the Library of Congress.