When co-blogger Chris Hendrix started off a series a couple of years ago on the origins of immigration restrictions, he fittingly began with the Chinese Exclusion Act (1882), looking at the arguments made for the act at the time. He examined them both the evidence available at the time and the evidence that has emerged since then. In a subsequent post in the series, I briefly examined the early years of the implementation of the Chinese Exclusion Act (1882-1910). While both these posts examined some aspects of the Chinese Exclusion Act in some detail, there is a lot about the history and aftermath of the Act that went unexplored.

Recently, I had the opportunity to create a number of Wikipedia pages on topics related to the Chinese Exclusion Act: Chae Chan Ping v. United States, Angell Treaty of 1880, Chy Lung v. Freeman, Fong Yue Ting v. United States, and others. As I worked on these pages, I familiarized myself more with the situation surrounding the Chinese Exclusion Act. I became more convinced that a more in-depth look at the Chinese Exclusion Act would help shed light on the modern border control regime.

I therefore intend to do at least three more posts on the subject. The current post will focus on the key developments and tug-of-wars that occurred until about 1872 (with passing mentions of trends that would continue into the late 1870s). A later post will discuss the more eventful years starting 1873. The year 1873 was marked by the Panic of 1873, the beginning of an economic downturn in the United States. The economic downturn was likely a contributing factor to increased anti-Chinese sentiment over the coming years, and key legislative and judicial developments related to immigration happened beginning 1875.

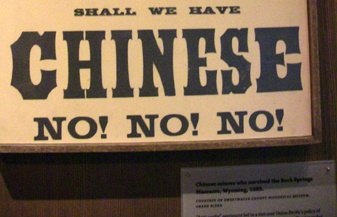

This post looks at the “keyhole solutions” used by state and local law enforcement in California before the federal government got on board with significantly restricting immigration.

Table of contents

- Limitations of my analysis

- How my thinking has evolved

- First, they came for the Chinese

- Migration began in 1815, but was negligible till 1848

- It began in California

- Migration patterns: the gender skew and the lack of babies

- Taxes on miners (1850 Act, 1851 Repeal, 1852 Act, gradual increase of license fee till 1870)

- Testimony, and People v. Hall

- Foiled attempts at outright bans on migration

- Lack of federal support for restrictions (in the 1850s and 1860s)

- Changes in the 1860s: the Transcontinental Railroad and the Civil War

- Miscellaneous remarks

Limitations of my analysis

Perhaps the biggest limiting factor to the quality of my analysis is the fact that such little data is maintained about that time period; in particular, about how ordinary people (both Chinese and the others in California) perceived the situation at the time. There is no Twitter, Tumblr, or Instagram to gauge public sentiment. There was no equivalent of Gallup polls. There were few newspapers and even those that existed don’t have all their archives available to peruse. Therefore, apart from actual legislative or judicial records, the main guidance present is various summaries provided by historians, who are in turn relying on observations penned by a few people, who may in turn have their own biases.

The lack of good resolution on who was thinking what leads to broad-brush generalizations in many parts of the text. I talk about the “Chinese” and “whites” but both groups were probably quite heterogeneous in terms of their habits, attitudes, beliefs about the other group, legislation they supported, etc. A more able historian with more time to research the issue and more space to devote to describing it would be able to pick nuances better. As such, please take any general statements I make about ethnic groups below with a large grain of salt: they are a third-hand summary of very incomplete data examined through possibly biased lenses.

How my thinking has evolved

Writing this post has led to some minor updates in my thinking. Here is a summary, that you can read without having to read the whole post.

- As I had previously noted in “Why was immigration freer in 19th century USA?”, there were no restrictions on immigration till the late 19th century (the Page Act of 1875 being the first federal regulation, and the Chinese Exclusion Act was passed in 1882). Even then, the first restrictions applied only to Chinese immigration. But I now see that the sentiment to oppose and restrict migration existed far in advance of actual restrictions, and the reason that it took so long to restrict immigration was mostly the federal structure of governance combined with the poor connectivity of California with the rest of the United States.

- This post also makes me more confident of observations I had made in my post on South-South migration and the natural state: despite the virulent and hostile response to Chinese immigration in California, migration remained freer and arguably closer to a state-of-nature than it does in the modern world.

- My feelings on “keyhole solutions”, and in particular, on the question of their feasibility and stability, have evolved a bit. I am now more convinced that they are not a stable equilibrium that placates those favoring restrictions. One reason is that some keyhole solutions, particularly those involving taxes and tariffs, can hurt migrants so much that their subsequent impoverishment makes them look even worse on social indicators to the rest of the population (a point related to what co-blogger Nathan alluded to in his post the dark side of DRITI). Another is that keyhole solutions need to be extremely punitive (at risk of impoverishing migrants and making them look worse) to make a significant dent in migration trends, to the level that would satisfy those who seek restrictions. Keyhole solutions at an intermediate level can generate revenue for government and can address rationally calibrated concerns about immigration, but they can’t really solve the public’s general aversion to migration. Keyhole solutions might work better in quasi-democratic settings. In quasi-democratic settings, not every individual policy choice is debated. Rather, as long as the quasi-democratically elected leaders’ overall performance meets natives’ expectations, they buy into the policy package despite not liking parts of it. A country like Singapore might be an example.

- Seeing the effects of migration isn’t guaranteed to drive one in favor of migration. In the case of events prior to the Chinese Exclusion Act, in fact, exposure to Chinese migrants led people to oppose it. California, which experienced the Chinese first, turned anti-migration first. Later, when the Chinese arrived in the Eastern cities, anti-Chinese sentiment also spread there. This does not mean that exposure to migrants always leads to anti-migration sentiment, nor does it mean that such anti-migration sentiment is factually grounded. Rather, we have to keep in mind existing narratives and biases that have been developed, in addition to the characteristics of migrants and natives, and results on sentiment towards migration could go in either direction. I don’t think nativist backlash is inevitable, but writing this post has led me to somewhat increase the importance I place on it as a force to reckon with.

First, they came for the Chinese

John’s post on tearing down Chesterton’s fence offers a good bird’s eye view of how immigration restrictions originated worldwide. While researching the subject, I noticed that in at least two other English-descended countries (Canada and Australia) the first significant immigration regulations appear to have been explicitly targeted at the Chinese, as I noted in an Open Borders Action Group post.

The situation in Australia closely paralleled the situation in California. In both cases, large numbers of Chinese moved to the area around 1850 in search of gold. In both cases, resistance to Chinese started off with native miners and labor unions of “natives” (i.e., whites, rather than the indigenous population), but gradually spread to the rest of society. Continue reading How did we get here? Chinese Exclusion Act buildup (1848-1872)