In our welcome blog post, we state:

This website is dedicated to making the case for open borders. The term “open borders” is used to describe a world where there is a strong presumption in favor of allowing people to migrate and where this presumption can be overridden or curtailed only under exceptional circumstances.

Many of our leading influencers and those associated with the open borders movement in some fashion spurn the label “open borders”, however. A good example is economist Michael Clemens. Clemens’s chief contributions to open borders are his work summarising the economic literature suggesting free migration would double world GDP and his analysis of the place premium showing the vast wage discrimination effects of the borders status quo. Clemens’s “double world GDP” is literally our website’s motto, yet in an interview with economist Russ Roberts, he states:

People often ask me if I am in favor of open borders. And I take an agnostic approach to that question. That’s kind of a strange term but by it I mean that I think the question is ill-posed. I don’t understand what people are asking when they ask it.

Do they mean anyone from everyone in the world should be able to freely move to every other spot on the world? Well, I don’t have that right right now. I don’t know of anybody who has ever had that right, actually. I can’t walk into your house. I can’t walk into a military base. I can’t go sit on the street–police would remove me after a while. My movements are tightly regulated. Property markets are regulating where I can pitch a tent and live.

If open borders means absolutely free movements then we certainly don’t have that in this country. If open borders means anybody can come get immediate access to any public service no matter whether or not they’ve paid into the system, that’s not something that I enjoy either. I don’t get to take Social Security money out unless I put money in. That’s also true for immigrants, by the way–you can’t get any money out of Social Security until you have paid into it for at least 40 quarters, that is a minimum of a decade of work or more. If open borders means absolutely free movement of people without any sort of tracking of who they are or any sort of concern for free riding in public services or any concern for trespassing on private property, then, no.

Open borders doesn’t exist in any space that I’ve ever seen. I don’t really want it to exist. Before we talk about open borders, I need to know what that means. Usually people mean something like a great relaxation to the policy barriers that people face right now.

Clemens quite clearly wants a “great relaxation” of barriers to human movement, which is how he ultimately winds up defining what people mean by “open borders”, yet he spends almost hundreds of words denouncing the label.

Take too philosopher Kieran Oberman, who supports the concept of a human right to migrate:

Commitment to these already recognized human rights thus requires commitment to the further human right to immigrate, for without this further right the underlying interests are not sufficiently protected.

Does this mean immigration restrictions are always unjust? On the view of human rights adopted here, human rights are not absolute. Restrictions might be justified in extreme circumstances in which immigration threatens severe social costs that cannot otherwise be prevented. Outside these circumstances, however, immigration restrictions are unjust. The idea of a human right to immigrate is not then a demand for open borders.

Rather it is a demand that basic liberties (to move, associate, speak, worship, work and marry) be awarded the same level of protection when people seek to exercise them across borders as when people seek to exercise them within borders. Immigration restrictions deserve no special exemption from the purview of human freedom rights.

Oberman too rejects the label of “open borders”, but he clearly believes that there is a human right to cross international borders that can only be restricted in the most extreme of circumstances. In other words, he accepts the presumptive right to migrate which we at Open Borders: The Case consider the clarion call of open borders, but rejects open borders!

On the flipside, consider philosopher Phillip Cole, who endorses a set of views virtually identical to Oberman’s in his defence of open borders:

…the right to cross borders is embodied in international law, but only in one direction. Everyone has the right to leave any state including their own. This is a right that can only be over-ridden by states in extreme circumstances, some kind of public emergency which threatens the life of the nation. What we have is an asymmetry between immigration and emigration, where states have to meet highly stringent tests to justify any degree of control over emigration, but aren’t required to justify their control over immigration at all.

In effect all I’m proposing is that immigration should be brought under the same international legal framework as emigration. Immigration controls would become the exception rather than the rule, and would need to meet stringent tests in terms of evidence of national catastrophe that threatens the life of the nation, and so would be subject to international standards of fairness and legality. This is far from a picture of borderless, lawless anarchy.

Cole describes his argument as making the case for open borders from the basic principles of human rights — just as Oberman does! The two endorse the same logic, and yet one embraces the label of open borders, and the other rejects it.

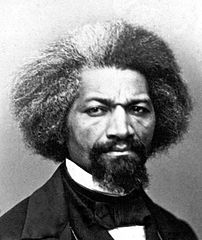

Rather than affirm or reject any one of these views (partial as I am to Cole’s views, I would also endorse almost everything I have seen from Clemens and Oberman when it comes to immigration), I would say this points to the nascent nature of the open borders movement. Although suspicion and hostility to the stranger in our land has almost always been a feature of human nature, it is not until recently that anyone has felt compelled to defend the right to migrate; strong outbursts of nationalism in the late 19th century compelled civil rights activists such as Frederick Douglass to speak out for open borders. But even in that climate, German legislators took it for granted that borders were to be crossed at will in peace (their only debate was over whether governments could arbitrarily deport migrants), and Argentina had no problem entrenching the rights of immigrants into its constitution.

The development of borders that are closed by default — the closed borders regime, I like to call it — is a historically recent feature. Because closed borders are so young, the movement to overturn them is even younger. It should not be terribly surprising then that different opponents of the borders status quo have different ways of describing their views, even if all have the same end in mind.

Beyond that, there are pragmatic reasons why we might want to avoid the label of open borders. A good one, exemplified in Clemens’s wariness of “open borders”, is the usage of this term by closed borders regime advocates as an instance of what blogger Scott Alexander calls the Worst Argument in the World:

I declare the Worst Argument In The World to be this: “If we can apply an emotionally charged word to something, we must judge it exactly the same as a typical instance of that emotionally charged word.”

Immigration restrictionists frequently tar moderate immigration liberalisations with the label of “open borders” — never mind that giving a few million people a reprieve from deportation is nowhere close to literally tearing down border checkpoints or striking thousands of immigration laws off the statute books. The reason they do this, as Clemens alludes to, is that many people, intentionally or otherwise, conflate free peaceful movement across borders with something far more extreme or obviously undesirable such as:

- the abolition of the nation-state

- the abolition of national defence

- free rein for criminals or infectious diseases to travel without inspection

- abolition of any individual right to exclude others from one’s private property as one sees fit

“Open borders” is meant to be pejorative; it is meant to be a dogwhistle, striking an emotional chord with people who consider it an emotional article of faith that sovereignty can never co-exist with open borders (never mind that nation-states existed for centuries after the Treaty of Westphalia without closing their borders). If restrictionists get away with taunting moderates for supporting slightly-less restrictive policies because they amount to “open borders”, imagine the opprobrium and the closed minds we may encounter if we publicly proclaim our support for open borders! So I perfectly understand Clemens’s eagerness to demur here, and state he supports freer human mobility across international borders in lieu of saying he supports open borders.

But what happens if we try Oberman’s preferred formulation? What if we just say we are for a right to migrate? Does this clear up the confusion, since one cannot accuse us directly of wanting to undermine the peace and security of modern societies? Does this preemptively address the unfounded concern that we are out to abolish the right of private property owners to exclude foreigners from their own living rooms and dining tables? It would seem not; on more than one occasion (here and here), I’ve encountered people who allege the right to migrate infringes individuals’ right to keep strangers out of their own homes.

To be honest, it does not bother me much either way whether we call it open borders, the right to migrate, human mobility, freedom of movement, or just the right to be left alone in peace. Whatever you call it, like all those I have cited, I believe in a world where any person who wants to go somewhere for pleasure, family, work, or study, and is willing to pay the fare it will take to get him or her there, will be able to do so in peace. And I believe a major precondition for getting there is to abolish most of the immigration laws in place today.

As I wrote during the Ebola crisis of 2014, immigration laws aimed at quarantining and treating infectious diseases do not bother me. I am no more distressed about immigration laws that prevent terrorists from entering than I am about trade controls that prevent international trade in weapons of mass destruction. But beyond these, I believe most immigration laws are spurious, unnecessary, and aimed purely at excluding people who have done nothing wrong except being born on the wrong side of an arbitrary line.

How do we operationalise open borders? How do we enact the right to migrate into law, and guarantee freedom of movement to all people? The nation-state is not going away any time soon, and so the answer lies in getting our nation-states to change their laws. I am on-board with the liberal premise that the ultimate purpose of government is to protect individuals’ liberty to go about their own lives in peace — and so as sympathetic as I might be to the utopic vision of having no borders at all, I believe we should at least hold our own governments accountable for protecting the liberties of all who seek protection and peace within our borders.

Clemens notes that he tries to refocus the discussion not on the semantics of “open borders”, but rather on what operationally we seek to achieve. I think we in the movement, wonks like Clemens aside, often shy away from articulating a specific policy we would like to see. Part of this is because the legal and policy analysis necessary to enact open borders has rarely been done, and would vary significantly from country to country. Our goal is simply to place freedom of movement on the political agenda in the first place — to force citizens to reckon with the malicious wrongdoings of our own governments in persecuting people who have done nothing wrong.

But a further part of this is also because, just as our goal has many labels, it also has many possible routes — we’ve discussed these paths to open borders plenty in the past and intend to keep doing so. And I do think one appeal of the “freedom of movement” or “right to migrate” labels is that they are somewhat more agnostic about which of the options we have are the best or the appropriate route(s) to take.

Open borders tends to imply, just as it says on the box, borders that are open. This would suggest borders with no checkpoints (perhaps just a sign such as “You are now entering Germany”), or borders with checkpoints where very few are stopped — i.e., guards are posted, but they do not stop anyone unless the person appears suspicious, similar to how guards are often posted in airports or train stations, but they do not stop anyone unless that person fits a suspicious profile.

You are now entering Germany; the Germany-Austria border. Original photographer unknown; image downloaded from The Lobby.

Meanwhile, freedom of movement and the right to migrate carry fewer explicit connotations about how our societies would in practice respect and protect these liberties. Of course, we could always abolish or minimise border controls, as literal open borders would suggest. But we could also simply offer visas to anyone who applies for them (subject to standard exclusions for people bearing diseases, weapons, or criminal intent of course). We could maintain checkpoints and inspect every traveller while still waving 98% of them through, as was actually done on the famous US checkpoint of Ellis Island in the era of open borders. Or we could even technically maintain more controls on immigration, while blatantly waiving most of these controls, as Argentina does.

But this potential semantic-implementation distinction does not bother me much either. After all, these days virtually every domestic traveller getting on an aeroplane at a regular port of travel is subject to a screening and document inspection of some kind. Beyond the most absolute of pedants, and a handful of laudable liberty-of-travel advocates, I think most of us would agree that this does not mean we lack internal open borders. The internal borders of our countries are porous to virtually all of us except those on government watchlists; our borders are internally open.

At the end of it all, I am less concerned about what kinds of checkpoints we have, or what screenings we may subject travellers to (as worthy a set of issues these might be) than I am about ensuring as many people travelling in peace are able to do so free from government agents standing in their way, preventing them from moving in peace with all the coercive force of the state. To my mind, it is a waste of taxpayer money, a danger to peace and safety, and worst of all abusive and discriminatory for law enforcement officials to be treating people seeking to visit friends and family or work for a fair wage as though they are dangerous criminals. It does nobody any good for our governments to consider peaceful, orderly movement a threat to the fundamental order of society.

It is this dangerous and unjust treatment of migration as a crime that I want to end. And I do not much care what we call our goal, or how we reach it. What I want is a world where my government, and every government, dispenses justice to every person seeking it from them. Where every government respects the right of individuals to go about their own lives and arrange their own affairs in peace, no matter their nationality or circumstance of birth.

A world with open borders; a world with freedom of movement; a world with the right to migrate. It matters not what we call it, but to all of us, it should matter very much that we achieve it. For as two German legislators rising in favour of abolishing deportation once said:

Liebknecht: A right that does not exist for all is no right.

Lasker: …it is a barbarity to make a distinction between foreigners and the indigenous in the right to hospitable residence. Not only every German, but every human being has the right to not be chased away like a dog.

The image featured at the top of this post is of graffiti in the city of Cardiff, the United Kingdom. Photo by David Mordey; original graffiti artist unknown.

Acuerdo de San Nicolás de los Arroyos, a treaty between different governors signed in 1852 to convene a Constitutional Convention that drafted the constitution of 1853, source

Acuerdo de San Nicolás de los Arroyos, a treaty between different governors signed in 1852 to convene a Constitutional Convention that drafted the constitution of 1853, source