Nathan just published a lengthy and detailed critique of various critics of open borders. I think he gets many things right, but in some ways he underestimates restrictionist arguments. This isn’t entirely Nathan’s fault — restrictionists often don’t frame their arguments cogently and clearly, and it’s extremely hard to understand their arguments without spending considerable time going through them. I want to talk about one particular restrictionist argument — the IQ deficit argument, and what I think an appropriate response to this argument is. This post is not intended to address specific restrictionist critiques of IQ. I’ll do that in subsequent posts. For now, my main goal is to explain my overall position.

Now, some open borders advocates find the entire discussion of IQ off-putting and are quick to make accusations of racism and invoke negative stereotypes for restrictionists. (To take just one example of where this came up, consider the comments section of this blog post where I came under fire for engaging IQ-based arguments in the context of immigration). I do not adopt this approach for multiple reasons, most important of which is that I think some of the basic premises underlying the IQ deficit concern are valid. And, my goal in this blog post is to address IQ-based objections, not to dismiss them.

I’ll state the IQ deficit argument for immigration to the United States, though the general framework is applicable to immigration to other countries as well.

- IQ is meaningful, measurable, and correlated with a number of real-world performance metrics. Higher IQ people tend to be more cooperative, less criminal, more innovative, better and more informed voters, etc. These correlations hold even after we control for other things such as education levels. A high IQ person without much formal education would tend to be more cooperative than a low IQ person with a similarly low formal education: Basically, I think this is correct. It seems to agree with the Mainstream Science on Intelligence and Intelligence: Known and Unknowns. Recent work by Garett Jones has strengthened economists’ appreciation of the link IQ and cooperation and its role in economic development, something whose implications I considered in this blog post.

- Adult IQ is fairly stable (though it can go down with head injuries and certain illnesses). It cannot usually be made to go up significantly. Childhood IQ may be malleable, but we don’t quite know how to manipulate it much on the positive side, though probably malnutrition and childhood disease affect it on the negative side. I think this is broadly correct too. This also agrees with the two consensus statements above.

- Under open borders, the average IQ of immigrants to the United States is lower than the average IQ of current United States residents: International IQ data comparisons are not very solidly established, but the preliminary evidence suggests that this is likely to be true. If Lynn and Vanhanen’s data are to be believed, then the average world IQ is about 2/3 of a standard deviation below average US IQ. I’m not very confident about this, but it’s plausible.

- The stability of adult IQ means that even after migration, the lower average IQ of immigrants will pull down the average IQ of the United States. This seems fairly plausible to me.

At this point, Nathan jumps in and says, “Ah! Even if correct, this is not as relevant as you think. You’re committing the maximize the average fallacy and refuse to understand the comparative advantage concept.”

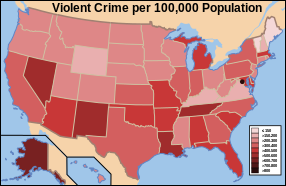

Not so fast, restrictionists would say. As Richard Hoste puts it, the comparative advantage argument works in the context of pure economics, but once we bring in crime and political externalities, it starts to falter. If crime rates go up, then your chance of being a crime victim goes up, all else equal (there are caveats to be added, but I’m using a simplistic picture of crime). Comparative advantage doesn’t come to the rescue here. And if low IQ means voting for bad policies (something that’s supported by Caplan’s research) then low IQ immigration would lead to negative political externalities.

So, I don’t think the comparative advantage argument is quite the right way to tackle the IQ deficit concern. So what is? I think we need to step back a bit and be clearer about how IQ matters to the moral and practical considerations that come up with respect to immigration and its effect on natives and immigrants. Does IQ matter in and of itself (as some indication of moral worth or desert), or does it matter because of its correlation with things like crime or political beliefs or social capital or what-have-you? It’s only the rare IQ elitist who argues that IQ is morally significant in and of itself. Most people who believe in the importance of IQ believe in it because it’s correlated with a lot of other things like crime, political beliefs, etc.

This brings me to the crux of my objection to the IQ deficit concern. If lower immigrant IQ raises concerns about higher immigrant crime rates or wrong political beliefs, then that should show up in the evidence on immigrant crime rates and political beliefs. If it does show up there, then great, score a point for restrictionists, and now that we’ve done that, what additional information does immigrants’ IQ deficit give us? By saying that immigrants commit crime and that immigrants have a low IQ which means they would commit more crime, it seems like restrictionists are double counting crime.

What if restrictionists are unsuccessful in demonstrating higher immigrant crime? That does seem to be the case with current levels of immigration to the United States. As things stand today, the foreign-born have lower crime rates than natives both in total and for every ethnicity and for every combination of ethnicity and high school graduation status.

Some restrictionists look these data in the eye and say, “Immigrants have lower IQ, therefore they must be committing more crime, no matter what the data say.” I think the data on crime rates aren’t wrong, so let me engage restrictionists by offering alternative explanations within their explanatory framework of low IQ being correlated with higher crime rates. The first possibility is that the restrictionists may be wrong about their claim of lower IQ of current immigrants to the United States. The second possibility is that there may be certain other differences between the foreign-born and native-born Americans that compensate for the lower average IQ to push the overall averages in the other direction. Those differences may be in terms of the culture or in terms of the structural incentives and constraints faced by the foreign-born relative to natives. But whatever the story, I think that when restrictionists find that a particular predicted ill-effect of low immigrant IQ fails to materialize, then they should give up on that and concentrate on the other claimed bad effects. And, perhaps, also double-check their claim of lower immigrant IQ while they’re at it.

So my overall claim is that restrictionists who think the IQ framework is a good overarching framework within which to fit their objections can certainly offer this framework. But they should not double count harms by both including the harm itself and the IQ deficit channel for the harm as separate harms. And if a harm predicted by IQ deficit fails to materialize, they should sportingly concede the point and move on. Which means that IQ deficit ultimately serves only as a framework, not as an argument in and of itself.

I will now address a few possible objections that restrictionists might raise to what I’ve said above. Continue reading IQ and double counting the harms of immigration →