I understand that the following is not a rigorous argument, just something to check intuitions that come so easily to many people.

Here’s the set-up: I will tell you about a country and its situation and you try to judge what happened to them. Are they being swamped by immigrants? Is there a threat of societal breakdown? Do they suffer economically? Is the political system in trouble? Etc.

However, I will not tell you which country I am talking about. For the moment it is just “Openbordia.” To obfuscate it a little, I will change some of the magnitudes. But you will see that I do it only on the side that goes against the usual intuitions. Then I will disclose the name of the country.

Just a fun game. Ready to play?

Okay, here goes …

Openbordia is a rather small country surrounded by much larger countries. There are four countries closeby. And there are plenty of other countries in the wider region. If the population of Openbordia is 100, the four closest countries come in at more than 1,000 each, and all the countries in the region together at more than 10,000. So it does not look good for Openbordians as they are outnumbered at least 100 to 1.

What makes the situation even more desperate is that Openbordia is also richer than the surrounding countries. Here’s GDP per capita (PPP, Worldbank figures for 2005-2012): If Openbordia is at 100, then the four closest countries only muster a meager 40, 44, 45, and 47. And it gets worse. One country in the region with already many emigrants to Openbordia stands at just 28. To be sure: they alone have more than ten times the population of Openbordia. And then there are other even poorer countries of similar sizes where it goes down to dismal levels of 24 for two countries much larger than Openbordia. And a little further away, there are two countries with more than ten times the population of Openbordia, but only levels of 18 and 17. So there are plenty and plenty of poor people surrounding Openbordia.

For comparison: If the US is at 100, then Russia is at 47, Mexico at 33, Venezuela at 27, China at 18, and Nigeria at 17. So if Openbordia decided to open its borders it would be like the US opening its borders for all those countries. But then the US is a much more populous country. It should be worse for Openbordia.

Now you would think that the Openbordians had learned something from reading restrictionist websites. But guess what, they have not. In a fit of complete delusion they threw their borders open with their two closest neighbors already decades ago. But remember: those two countries are still not even half as rich as Openbordia. So probably there was a lot of pressure from unchecked immigration.

With such an experience, you might guess that Openbordians had now at last read up on restrictionism. Well, they stayed completely deaf to it. Instead, they pushed for even more open borders. More then a decade ago, they got their two other close neighbors to open their borders, too. As those two countries are even larger than the first two countries, that should have made the situation untenable. However, the Openbordians ignored the peril they were in and, hard as it is to believe, even prided themselves that the open border treaty was named after a town in their country!

At that point, you’d expect some prominent restrictionist to intervene and write a blog post telling the Openbordians that they were headed for doom. As far as I can see, restrictionists completely missed the problem. And Openbordians went on with their rampage against borders. Already years ago they did away with them also for lots of other countries in the region, all the way down first to the level of 24% of relative GDP per capita and then even to the level of 17%.

This is a disaster waiting to happen, right?

No, this is Luxembourg. The “poor” countries in their neighborhood are The Netherlands, Belgium, Germany, and France. The country many immigrants have come from is Portugal. The countries in the region at 24% of GDP per capita are Poland and Hungary. Romania is at 18% and Bulgaria at 17%.

Luxembourg has been in a customs union with The Netherlands and Belgium since 1948, and completely opened its borders in 1960. The Schengen Treaty with those two countries as well as France and the Federal Republic of Germany was signed in 1985, has been effective since 1995, and is named after the town Schengen in Luxembourg. The Schengen Area grew from there and now encompasses countries with a population of more than 400 million people. Since Luxembourg only has about half a million inhabitants, they are outnumbered not just 100 to 1, but almost 800 to 1.

The last time I was in Luxembourg is more than a decade ago. It looked rather tranquil then. But I may have missed something and things went downhill from there. Give me a little time to do the research. Restrictionist websites will certainly have lots of posts on Luxembourg …

Additional Remarks

- One objection might be that GDP per capita is not the correct measure here. However, other measures do not yield materially different conclusions about the relative position of Luxembourg vis-à-vis its neighbors. Take e.g. average net monthly wages. Luxembourg has an average of $4,230. The Netherlands, Belgium, Germany, and France come in at $2,671, $2,496, $2,865, and $2,845, or roughly 60% to 70% of Luxembourg wages. Portugal has $1,164 or 28%, which is about the percentage also for GDP per capita. Poland and Hungary at $866 and $856 look even poorer with a level of only about 20%. And Romanians and Bulgarians at $485 and $414 earn only 11% and 10% of Luxembourg wages.

- As I said at the start, this is not a rigorous argument that can prove all that much about other countries. Or at least I would have to work harder. However, I don’t think the example of Luxembourg can’t prove anything at all. It is a counter-example to many common intuitions:

- “With lots of potential immigrants that are poorer and often much poorer, a small country is bound to be swamped.” — Foreigners are making up 38% of the population (the most for any European country), but Luxembourgers are still a majority. There is no takeover going on that I am aware of.

- “With so much immigration, a country runs into economic problems. Competition from poor people will make domestic citizens poor, too.” — But Luxembourg is doing fine economically, as the country with the highest GDP per capita in the world according to Worldbank figures. Wages are a lot higher than in Germany or in France.

- “Their wealth and the steep differentials with other European countries will attract lots of criminals.” — But then the homicide rate is at 0.6 per 100,000 a year, which is way lower than in the US at 4.7, and even lower than in neighboring Germany at 0.8 and France at 1.1.

- “They must be overrun by people only trying to collect welfare.” — Still they have one of the lowest unemployment rates in Europe, lower than Germany and much lower than France. And if the Luxembourg government had to shell out so much in welfare, how come they have much lower tax rates than Germany and France?

- I really ran a search for “Luxembourg” at the VDARE website, but could not find anything. That’s strange. Luxembourg should be a poster child for demonstrating all the pathologies of immigration. In every dimension, it looks like Luxembourg is in the worst possible position of any European country. This should be a bonanza for restrictionists, and I am giving it away for free.

- You may ask: How can wage differentials persist for long times? One reason is that labor is not homogeneous, so many potential immigrants do not compete for the same jobs because they do not have the respective skills. Luxembourg is geared towards the banking sector, so competition comes from other such cities, e.g. Zurich, Frankfurt, and London, where wages are also high. It is not as if hundreds of millions could “take away” specialized jobs and drive down wages only because they come from poor countries and are willing to work for low wages. Another possible reason might be cultural and/or linguistic. Many immigrants find it easier to emigrate to countries that are culturally and linguistically similar to their home country. Luxembourgers are fluent in both German and French, and in addition speak their own language, Lëtzebuergesch, which could be viewed as a German dialect strongly influenced by French. The francophone component may explain the rather high proportion of Portuguese immigrants (as for France, but unlike Germany). In general, migration within the EU is lower than would be expected from wage differentials. Here are two papers on the phenomenon:

- Michèle Belot and Sjef Ederveen: “Cultural barriers in migration between OECD countries”, who find that the main reason is cultural.

- Alicia Adsera and Mariola Pytlikova: “The role of language in shaping international migration”, who view linguistic dis/similarities as the main explanation.

Linguistic and cultural barriers may make it harder to capture gains from open borders as predicted by models that only rely on wage differentials as the driving force. This perhaps cuts somewhat against the most optimistic predictions on the open borders side — but also against restrictionist predictions of large inflows of culturally dissimilar immigrants. According to the Gallup Survey on International Migration 35 million people worldwide are interested in migrating to Spain, but only 25 million to richer Germany.

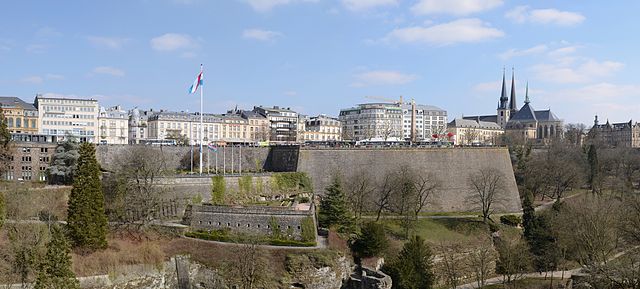

The photograph of Luxembourg featured at the top of this post was taken by Marcin Szala and is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike licence.

This does, in fact, illustrate a condition where open borders work: when the plausible migrants are “compatible enough” even when not as wealthy.

But it’s up to existing citizens to judge whether that’s the case; strip them of the right to make that judgment, and you end up with many of the same problems associated with taking away other property rights.

But then these immigrants come from the same countries as do immigrants to other European countries where it is said they are causing major problems. The only difference is that there are more of them relatively in Luxembourg although I have never heard the explanation that other European countries have too few of them.

Last I checked, it was Roma, Muslims, and perhaps Africans which have a track record of widespread incompatibility with European host countries. (There are specific ethnic hatreds on top of this, but they don’t involve Luxembourg.) As long as those groups continue to have little interest in migrating to Luxembourg in significant numbers (looks like the current Muslim proportion is less than 2%), I wouldn’t expect problems. If that situation changes, I’d expect interest in immigration restriction to greatly increase.

There were 2.3% muslims in Luxembourg as of 2010. That’s less than for the countries closeby: Germany 5%, France 7.5%, Belgium 6% and the Netherlands 5.5%, but in a similar range as for other European countries, e.g. Norway 3%, Italy 2.6%, Spain 2.3%. Many other countries fall somewhere in between: Denmark 4.1%, the UK 4.7%, Sweden 4.9%. (Source: http://features.pewforum.org/muslim-population/)

If I understand you correctly then a percentage of 2.3% muslims does not lead to noticeable problems. How can an extra 2% to 3% change the picture completely? Those are the same type of people after all.

Okay, 2% was a slight underestimate, thanks for the link.

The level of native discontent seems to be roughly proportional to size and cultural distance. Luxembourg’s Muslims seem to be largely drawn from the former Yugoslavia; they’re plausibly less culturally distant than Muslim immigrants from north Africa/the Middle East would be.

Empirically, France’s 7.5% (mostly descended from north African immigrant) share is enough to cause significant discontent. While not too much larger than 2.3% as an absolute number, the [size] * [cultural distance] product is nevertheless more than six times as large as for Luxembourg (if we model France’s Muslims as being twice as culturally distant as Luxembourg’s), so it’s not unreasonable for the outcomes to be qualitatively different.

My point was not about the perception of there being a problem. I am well aware that many Europeans have such a perception regarding immigrants, and especially immigrants from muslim countries. My point was about whether the perception has a base in reality and there really is such a problem. If not, natives are the problem, not immigrants. If there is a problem, but the perception is out of proportion with it, then mostly natives are the problem and immigrants only in a minor way.

That can happen, and so it is not sufficient to point out that there is the perception of a problem to prove there is one. (Interestingly enough, your own explanation does not assume there really is a problem, only that there are people with a different cultural background and how many they are.) If you had gone to European countries in the 1920s, you would have heard lots of people claim there was a serious, maybe deadly problem with Jews. None of that was true. Whole societies can pursue such delusions.

As for your theory about what drives such perceptions: I guess there is a kernel of truth in it, that human beings will view people who are unlike them with more distrust. If so, it looks more like an imperfection of the human mind than an apriori proof that the distrust has a base in reality.

And it is not clear whether higher numbers increase or decrease distrust. If there are very few people of a certain group around, it is much easier to entertain delusional views about them. The more there are, the more you know what they are like, the more you can see that there are all kinds of people in the group and that they are not all the same, etc. You have more data you have to reconcile with your views. So it becomes harder to stray from reality.

Here are two examples:

– In Imperial Germany, Saxony was a hotbed of antisemitism. Antisemites could win majorities in parliamentary elections there. However, there were hardly any Jews in Saxony. Berlin had 5% Jews, Frankfurt 10% Jews, but antisemites were especially unsuccessful there (of course, there were also some).

– After reunification, East Germany had almost no immigrants, practically all of them were in West Germany. When there was sometimes pogromlike rioting in the 1990s, it was disproportionately concentrated in East Germany. Here’s a paper by Krueger and Pischke: “A statistical analysis of crime against foreigners in unified Germany” – http://dataspace.princeton.edu/jspui/bitstream/88435/dsp01f7623c59w/1/358.pdf

“mostly natives are the problem”

If so, I’m pretty darn sure totalitarian override of popular will is a “solution” worse than whatever problem you think is being solved. (And the primary job of country X’s government is to effectively tend to matters concerning country X’s people, not everyone in the world. That’s why it’s just country X’s government instead of an international government.) So, no, you’re wrong: it is sufficient for me to point out a common perception of a problem.

If you’re that sure you understand these dynamics better than the natives, your job is to convince, not coerce, them. As I’ve mentioned repeatedly in other comments, there are small countries which have native majorities supporting substantially higher immigration; you can cooperate with one or more of them to work toward a real demonstration of a high-functioning open borders society. I predict that the generation of advocates which is finally serious enough to work on something like this is the one that will sustainably advance your cause; until then, the more you cooperate with hostile elites who agree that “natives are the problem” and are working on “solving” that, the more hatred you’ll receive and deserve from those natives.

How about addressing the argument I actually made, and not just a few words that are misleading without context?

Here’s the argument:

If you have two groups, A and B, and A entertains delusional views about B, then there is a problem with A, and not B. (Take A = anti-Semites and B = Jews as an example).

If you have two groups, A and B, and A entertains views on B that are vastly overblown, then the problem mostly lies with A, and not B.

These two assertions seem almost tautological to me. It doesn’t matter whether A is a majority or even the entire population. The point is that what they believe is not true or vastly overblown. This doesn’t change because many people believe it.

Apart from that: I am not asking for totalitarian measures, but only that others do not take them, especially when they are acting on deluded or vastly overblown assertions. Open borders does not mean forcing others to do anything, only that others refrain from using force themselves. That’s pretty much the opposite of what you write is my opinion.

For a real world example: try Luxembourg. Not perfect by open borders standards, but then also not bad.

“Open borders does not mean forcing others to do anything, only that others refrain from using force themselves.”

In the sense that asking law enforcement to refrain from protecting [organization X]’s property while a bunch of yahoos look at and take what they want is not “forcing [organization X] to do anything”, yes.

Systems granting private property rights are currently best-of-breed at a variety of levels, and they require judicious use of force to work. Private property rights include the right to make “wrong” judgments which are limited in scope to the property in question. This is fine because the frequency of “wrong” judgments will naturally decrease over time if there is room for meaningful competition. And there are over 200 countries in the world, and previous blog posts here which have established that at least a few of them are viable bases for consensual open borders experimentation (heck, Singapore’s leadership has engaged in a form of this and by conventional metrics it has one of the highest standards of living in the world; so you’re certainly not restricted to “hellholes”).

Insistence on stripping away limited-scope property rights, instead of just letting the “wrong” ideas fade out in peaceful competition, implies that you do not actually think the natives’ policies are ineffective. Singapore’s leadership has never believed they have no right to enforce entry rules; they voluntarily relax (or tighten) them in ways they see fit.

Finally, I had already said that I predict minimal problems for Luxembourg going forward as long as the problematic groups I named do not migrate there in large numbers. Best of luck to the Luxembourgers.

Maybe I misunderstand your argument, but it looks like we agree:

– I am all in favor of law enforcement (or anybody else) protecting [organization X]’s property. Why would I not?

– I am also in favor of respecting property rights: that anybody can decide whom to rent or sell to, whom to hire or support, whom to work for, rent or buy from, etc. = open borders.

– Luxembourg has been doing fine with immigration. I don’t see reasons to believe that will change in the future.

You disagree with most people, including me, in the last two words of #2. The international consensus is that countries have the right to set and enforce entry rules; this is essentially a form of property right (yes, with extra legal wrinkles because countries have enforcement responsibilities that corporations and smaller organizations don’t).

Up to the last two words, you’re fine: an employer from country A can always hire a worker from country B on a full-time basis if they both move to open borders country C, in the unfortunate case where country A won’t let the worker immigrate and country B won’t let the employer immigrate. (Heavy *exit* restrictions would get in the way of this, but fortunately Eastern European communism’s fall has mostly eliminated them, and established them as generally evil.) But no, neither employer A nor worker B have a right to override their home countries’ entry rules; they should either find a way to work within them, persuade their countrymen to revise them, or *both* find a new country.