As the arrival on the U.S. border of thousands of minors from Central America has consumed the attention of U.S. politicians and the media, open borders is rarely suggested as a policy option. One exception is the Libertarian Party, which has issued a strong statement in favor of open borders for these children, as well as most other would-be immigrants. Another, noted in a previous post, is from Ross Douthat of the New York Times: “One answer, consistent and sincere, is that the child migration really shows we need an open border — one that does away with the problems of asylum hearings and deportations, eliminates the need for dangerous journeys across deserts and mountains, and just lets the kids’ relatives save up for a plane ticket.”

As Mr. Douthat suggests, open borders would release the government from spending enormous amounts of money detaining Central American child migrants and adjudicating their cases. (President Obama is requesting billions more for these purposes.) Open borders also would help the child migrants and their families immensely. Families could be more easily reunited and wouldn’t have to pay thousands of dollars to have their children smuggled into the U.S., and the children wouldn’t be exposed to dangers on their long journey to the border, nor would they have to endure often miserable stays in U.S. detention. The children also could escape horrendous conditions in their home countries, without the fear that they would be deported back.

Related to the inability to consider the open borders option for these child migrants are references to the situation as a “crisis” (here and here) or a “problem.” Apprehending, detaining, and adjudicating the children is a self-imposed policy choice Americans have made, and it is this interference with the migration flow that is creating the strain on government resources. Without this interference, the “crisis” or “problem” wouldn’t exist for the government. The child migrants would travel safely to the U.S., disperse throughout the country, link up with (or arrive with) family, and start new lives. Some schools may see an increase in their student populations, which would involve some strain and expense for school districts, but eventually the children, like their U.S.-born peers, would become working members of society. (See here for information on the economic impact of immigration on the receiving country.)

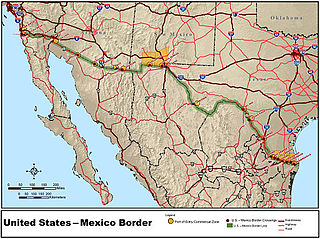

Beyond these self-evident advantages of open borders in addressing the child migration flow, here are three additional thoughts about the flow and the commentary surrounding it. The first is that given the dire conditions and limited resources for children in Honduras, El Salvador, and Guatemala, the source countries for most of the recent child migration, the U.S. should facilitate their migration, in addition to opening the borders. Loans could be provided to families or individual children to use for air transportation to the U.S., and once families are working they could begin to repay the loans. This support could be provided exclusively by private organizations and individuals, but in a previous post on facilitating migration, I noted that the government may be in a better position to help than private entities. As previously mentioned, this would allow poor families to avoid ground transportation through an often dangerous Mexico. It also would enable them to quickly escape the violence and poverty endemic in their homelands. Graphic descriptions of the dystopian conditions in the three aforementioned countries have appeared in recent articles and reports, including the following from the New York Times about conditions in Honduras:

Narco groups and gangs are vying for control over this turf, neighborhood by neighborhood, to gain more foot soldiers for drug sales and distribution, expand their customer base, and make money through extortion in a country left with an especially weak, corrupt government following a 2009 coup… Carlos Baquedano Sánchez, a slender 14-year-old with hair sticking straight up, explained how hard it was to stay away from the cartels. He lives in a shack made of corrugated tin in a neighborhood in Nueva Suyapa called El Infiernito — Little Hell — and usually doesn’t have anything to eat one out of every three days. He started working in a dump when he was 7, picking out iron or copper to recycle, for $1 or $2 a day. But bigger boys often beat him to steal his haul, and he quit a year ago when an older man nearly killed him for a coveted car-engine piston. Now he sells scrap wood. But all of this was nothing, he says, compared to the relentless pressure to join narco gangs and the constant danger they have brought to his life. When he was 9, he barely escaped from two narcos who were trying to rape him, while terrified neighbors looked on. When he was 10, he was pressured to try marijuana and crack. “You’ll feel better. Like you are in the clouds,” a teenager working with a gang told him. But he resisted. He has known eight people who were murdered and seen three killed right in front of him. He saw a man shot three years ago and still remembers the plums the man was holding rolling down the street, coated in blood. Recently he witnessed two teenage hit men shooting a pair of brothers for refusing to hand over the keys and title to their motorcycle. Carlos hit the dirt and prayed. The killers calmly walked down the street. Carlos shrugs. “Now seeing someone dead is nothing.” He longs to be an engineer or mechanic, but he quit school after sixth grade, too poor and too afraid to attend. “A lot of kids know what can happen in school. So they leave.”

The New York Times piece adds that “asking for help from the police or the government is not an option in what some consider a failed state. The drugs that pass through Honduras each year are worth more than the country’s entire gross domestic product. Narcos have bought off police officers, politicians and judges. In recent years, four out of five homicides were never investigated.” (See also here for information on conditions in El Salvador and here for conditions in a number of countries.)

The second idea is that the emphasis that some are putting on ensuring that the child migrants receive due process to determine if they are refugees, while possibly helping some immigrants stay in the U.S., is harmful to the open borders cause. It helps to legitimize the exclusion of those who are not determined to be refugees. Sonia Nazario, the author of the aforementioned New York Times piece describing conditions for children in Honduras, urges the creation of refugee centers in the U.S. where the children’s cases can be adjudicated. She emphasizes the need for officers and judges to be “trained in child-sensitive interviewing techniques” and that children be represented by a lawyer. However, she doesn’t hesitate to condone deportation for economic child migrants: “Of course, many migrant children come for economic reasons, and not because they fear for their lives. In those cases, they should quickly be deported if they have at least one parent in their country of origin.” Similarly, Jana Mason, a United Nations employee, states that “… these children, if they need it, should have access to a process to determine if they’re entitled to refugee protection. If they’re not, if they don’t meet that definition, we fully understand, then they’re subject to normal U.S. deportation or removal procedures.” Their implied message is that if the children get a fair examination of their refugee claims, they have been treated fairly, even if they end up being deported.

So what Ms. Nazario and Ms. Mason are saying is that if the only problem Carlos, the previously mentioned 14 year old, has in Honduras is that he only gets to eat two out of every three days and lives in a tin shack, he shouldn’t be allowed to emigrate to the U.S. And some children do want to migrate for economic reasons. In a recent survey of Salvadoran children who wish to migrate to the U.S., some cite this reason for wanting to migrate. Referring to children living in the most impoverished areas of the country, the survey’s author writes that “this desire for a better life is hardly surprising, given that many of these children began working in the fields at age 12 or younger and live in large families, often surviving on less than USD $150 a month.” Ms. Nazario and Ms. Mason also imply children shouldn’t be allowed to migrate if their sole reason is to reunite with family already in the U.S., but again many want to migrate for this reason. According to the survey of Salvadorans, about half have one or both parents in the U.S., and about one third identify family reunification as a reason for them to migrate.

John has noted that this effort to exclude non-refugee migrants can result in the exclusion of refugees. Notwithstanding Ms. Nazario and Ms. Mason’s emphasis on a pristine asylum process, the process of identifying who qualifies can be flawed, especially if you consider the history of asylum adjudication. As I’ve written previously, asylum is very narrowly defined under the law, and it is easy for asylum applicants to not qualify. Furthermore, when politics intrude, asylum decisions can be tainted. During the Cold War, asylum seekers from Communist countries were favored over those from non-Communist countries, including El Salvador and Guatemala, according to Bill Frelick and Court Robinson (International Journal of Refugee Law, Vol. 2, 1990) And the recent arrival of immigrant children has become highly politicized, with “pressure on the president from all sides,” according to The New York Times. The Times reports that “… administration lawyers have been working to find consistent legal justifications for speeding up the deportations of Central American children at the border…” In addition, the outcome of an asylum case can depend greatly on who is adjudicating the case. Finally, as Ms. Nazario suggests, if the U.S. doesn’t make it easier to apply for refugee status in Central America, refugees will still have to make a dangerous journey to the U.S. to even be able to apply for asylum.

The larger point is that it is immoral, with some rare exceptions, to stop people from migrating, regardless of their reason for doing so. There is, as John suggested recently, no justice in “an immigration system which arbitrarily excludes innocent people purely because of their condition of birth…” Similarly, the group No One is Illegal, which supports open borders, suggests that it is morally impossible to bar some immigrants while allowing others to enter: “… the achievement of fair immigration restrictions — that is the transformation of immigration controls into their opposite — would require a miracle.” Refugee advocates like Ms. Nazario and Ms. Mason, by emphasizing a distinction between those who deserve to be allowed to immigrate and those who do not, do harm to the effort to achieve the ability of all people to migrate freely.

The third idea is that the U.S. may bear some responsibility for the violent conditions in Central America. In the case of Guatemala, the U.S. helped overthrow a democratic government in the 1950s, leading to a succession of repressive regimes and a civil war with massive killings of civilians by the government. While it is difficult to prove causation, this legacy may account for some of the country’s current violence and poverty. In addition, the U.S. deportation of Central American immigrants in the 1990s apparently has contributed to violent conditions in El Salvador, Honduras, and Guatemala. Matthew Quirk, writing in The Atlantic six years ago, explained this link: A small number of Salvadoran immigrants formed the MS-13 gang in Los Angeles in the late 1980s,

but MS-13 didn’t really take off until several years later, in El Salvador, after the U.S. adopted a get-tough policy on crime and immigration and began deporting first thousands, and then tens of thousands, of Central Americans each year, including many gang members. Introduced into war-ravaged El Salvador, the gang spread quickly among demobilized soldiers and a younger generation accustomed to violence. Many deportees who had been only loosely affiliated with MS-13 in the U.S. became hard-core members after being stranded in a country they did not know, with only other gang members to rely on… MS-13 and other gangs born in the United States now have 70,000 to 100,000 members in Central America, concentrated mostly in El Salvador, Honduras, and Guatemala. The murder rate in each of these countries is now higher than that of Colombia, long the murder capital of Latin America.

Finally, the Libertarian Party has pointed out that “… U.S. government policies have caused the conditions that some of these Central American children are fleeing. The War on Drugs has created a huge black market in Latin America, causing increases in gang activity and violent crime.” (For more information on connections between the drug war and immigration, see here.) While U.S. contributions to problems in certain countries may not support a case for open borders, it does add another layer of U.S. responsibility for doing what is just for migrants from these countries.

In conclusion, establishing an open borders policy, combined with U.S. facilitation of migration, is the only moral and pragmatic response to the influx of Central American children. Efforts to aid only a portion of the children in their quest to stay in the U.S. are morally insufficient and help to justify immigration restrictions.