I was looking for books on immigration, and came across this title: Crowded Land of Liberty: Solving America’s Immigration Crisis. Perhaps I’ll read it sometime, but this post is a response to the fallacy expressed in the title. It reminds me of a long debate I had on immigration with someone I respect a great deal. We had gotten stuck for hours on an ethical question, whether it can be good to avoid seeing someone in suffering so as to avoid becoming callous—I said no—but after that it somehow came out that he actually thought another argument was the clincher, and so obviously so that my advocating open borders at all could only come from a willful blindness to, or a disingenuous refusal to acknowledge, this clincher argument, which to him was of course the reason that of course we had open borders then but can’t have them today.

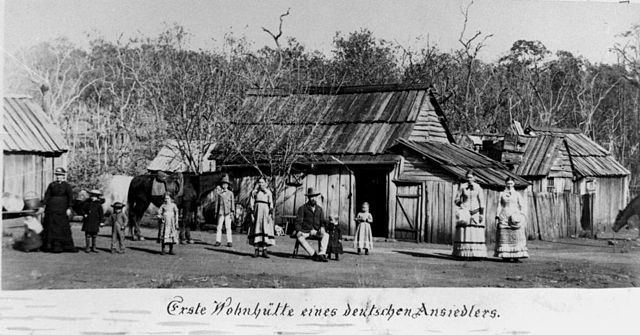

I will try to state this argument as sympathetically as I can. In the 19th century, America was a big, empty country, we needed people to settle it. America had open borders, not because we had any qualms about restricting migration, but simply because it wasn’t in our interest to restrict immigration when we had so much empty land. Today, the situation is different. The country already has plenty of people. It is even rather crowded. We don’t need more. On the contrary, more people would impoverish us, crowding us still further. Our new, more restrictive policy reflects the changes in our conditions and national interests. Such is the “this land is full” fallacy.

I was caught off guard by this argument because the intellectual communities I’ve been in for the past few years have consisted largely of economists or people trained in economics. Economists might sometimes fall for the “this land is full” fallacy, if their analytical brains aren’t turned on and they’re just being normal people. But to an economist qua economist, this fallacy would hardly occur, and if it did, it can be summed up and seen through quite quickly. Continue reading The “This Land is Full” Fallacy