Restrictionists frequently try to marginalize the arguments of open borders by claiming that, as Steve Camarota put it in our TV debate, “all societies, all sovereign states throughout all history have always had the idea that they can regulate who comes into their society,” or more generally, by treating state sovereignty as a universal norm of human life and migration restrictions as an essential element of sovereignty. In fact, passport controls were the exception rather than the rule until the early 20th century, and as far as I have been able to judge the evidence (but more research would be useful), there is little by way of analogous institutions in former times. What there is evidence for is a norm of hospitality across many cultures.

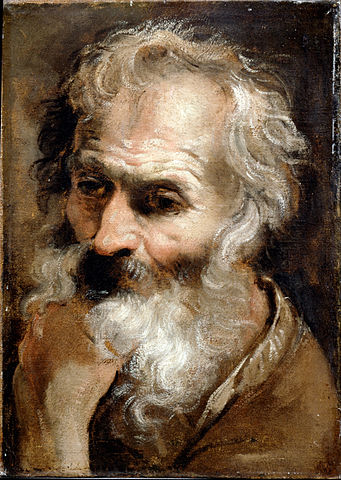

In particular, hospitality is perhaps the foremost moral theme of The Odyssey, one of the two great epics of ancient Greece. It was written (according to tradition) by Homer, who was also the author of the other great Greek epic, The Iliad. The Odyssey and the Iliad were to the Greeks a little like the Bible to the Jews: major source books of ethics, theology, and history; central reference points for the culture; definers of the Greek identity. The great difference in character between the Greek epics and the Bible expresses very well the great difference in character between the Greeks and the Jews. I previously wrote about the immigration policy encoded in the Mosaic law of the Old Testament. Having formed my open borders views, and even written a book about it, long before I studied the Old Testament teachings on the treatment of the foreigner, I was amazed at the extent to which the Bible confirmed my views, if indeed it does not go even farther than I had dared to go in insisting that strangers be welcomed and well-treated. In its own, quite different way, yet hardly less emphatically, the Odyssey, too, gives open borders supporters all they could ask for.

Odysseus, the hero and namesake of the Odyssey, is a Greek king from the heroic age, who participated in the great war that ended in the destruction of Troy. That war originated in the pollution of hospitality by Paris, the Trojan prince who was a guest of Spartan king Menelaus and seduced his wife Helen. Hospitality is a two-way street. Guests as well as hosts have obligations. On his return voyage, however, Odysseus runs into all sorts of troubles and disasters that keep him from getting home. The epic begins about twenty years after the fall of Troy, by which time Odysseus’s house has been overrun by men– “the suitors”– who are wasting his goods and seeking to marry his wife. The suitors, those unwelcome guests, are the villains of the epic, who in the climax of the story are slaughtered by the returning Odysseus. Again, hospitality is a two-way street, but it would be a stretch to compare the suitors to illegal immigrants, for it is not their mere presence in the household, but their theft of Odysseus’s goods and their hopes of marrying Odysseus’s wife that seem to make them the villains. Worse, at one point they plot to murder Odysseus’s son. Moreover, when Odysseus returns in the guise of a wandering beggar, they treat him with great inhospitality. Thus they deserve their fate.

Meanwhile, Odysseus is a love-slave on the island of the goddess, Calypso, but in spite of her divine embraces, yearns to return home. At last, the gods grant him to sail to the country of a people called the Phaecians, where they know, but Odysseus does not, that he will be well-treated and given passage back to his home country of Ithaca. After a rough sea voyage he is wrecked on the Phaecian coast, where he says (this is in Book VI):

“Alas,” said he to himself, “what kind of people have I come amongst? Are they cruel, savage, and uncivilized, or hospitable and humane? I seem to hear the voices of young women, and they sound like those of the nymphs that haunt mountain tops, or springs of rivers and meadows of green grass. At any rate I am among a race of men and women. Let me try if I cannot manage to get a look at them.”

Note the dichotomy Odysseus makes here. A people may be (a) cruel, savage, and uncivilized, or (b) hospitable and humane. Hospitality, humane treatment of guests, is the first, defining feature of civilized peoples. Of course, it might only be uppermost in Odysseus’s mind because he will soon be obliged to seek their hospitality. Still, the identification of hospitality with civilization shows the importance of this norm.

Shortly afterwards, Odysseus (known to the Latins as Ulysses) finds himself in the court of King Alcinous of the Phaecians, where (in Book VII) he presents himself as a suppliant:

So here Ulysses stood for a while and looked about him, but when he had looked long enough he crossed the threshold and went within the precincts of the house… Every one was speechless with surprise at seeing a man there, but Ulysses began at once with his petition.

“Queen Arete,” he exclaimed, “daughter of great Rhexenor, in my distress I humbly pray you, as also your husband and these your guests (whom may heaven prosper with long life and happiness, and may they leave their possessions to their children, and all the honours conferred upon them by the state) to help me home to my own country as soon as possible; for I have been long in trouble and away from my friends.”

Then he sat down on the hearth among the ashes and they all held their peace, till presently the old hero Echeneus, who was an excellent speaker and an elder among the Phaeacians, plainly and in all honesty addressed them thus: “Alcinous,” said he, “it is not creditable to you that a stranger should be seen sitting among the ashes of your hearth; every one is waiting to hear what you are about to say; tell him, then, to rise and take a seat on a stool inlaid with silver, and bid your servants mix some wine and water that we may make a drink-offering to Jove the lord of thunder, who takes all well-disposed suppliants under his protection; and let the housekeeper give him some supper, of whatever there may be in the house.”

When Alcinous heard this he took Ulysses by the hand, raised him from the hearth, and bade him take the seat of Laodamas, who had been sitting beside him, and was his favourite son. A maid servant then brought him water in a beautiful golden ewer and poured it into a silver basin for him to wash his hands, and she drew a clean table beside him; an upper servant brought him bread and offered him many good things of what there was in the house, and Ulysses ate and drank. Then Alcinous said to one of the servants, “Pontonous, mix a cup of wine and hand it round that we may make drink-offerings to Jove the lord of thunder, who is the protector of all well-disposed suppliants.”

In this passage, it is clear that King Alcinous has some authority to decide who will be received in his hall, though it does not follow that he gets to decide who is present on the territory of his kingdom. But the king is not exactly at liberty to exercise this authority simply as he happens to prefer. Echeneus, who is characterized as an “old hero,” suggesting an exemplar of virtue, declares that it is “not creditable” to treat “a stranger” otherwise than to welcome him by giving him an honorable seat. Moreover, there is a theological justification for this: “Jove [Zeus] takes all well-disposed suppliants under his protection.” Here there is a striking parallel with the Old Testament, where it is written that God “defends the cause of the fatherless and the widow, and loves the foreigner residing among you, giving them food and clothing” (Deuteronomy 10:18). Clearly, Echeneus is not making this up, but rather expressing the conventional wisdom, “speaking plainly and in all honesty,” and the king quickly echoes him, saying that “Jove [Zeus] the lord of thunder… is the protector of all well-disposed suppliants.” Continue reading Hospitality in The Odyssey →