See also: libertarian case, moral case, obligations to strangers

This libertarian principle says that the right of free mobility is a natural right and cannot legitimately be restricted unless there is strong evidence that the exercise of this right would violate other rights. A common formulation of this is that there is no morally relevant distinction between migration that occurs within national boundaries and migration that occurs across such boundaries.

There are many different levels at which one may endorse this right:

- An absolute right to migrate: This right is endorsed by some absolutist libertarians and anarchists, and also by some people of other political philosophies.

- A presumptive right to migrate: Here, there is a strong presumption in favor of letting people migrate that can be overridden only in the presence of clear evidence of harm or danger.

- A prior in favor of the right to migrate, or, the right to migrate as a useful rule of thumb: Here, the right to migrate is not treated as a “right” in a moral sense, but is rather considered a useful rule of thumb for some other end. For instance, a utilitarian may favor a right to migrate as a useful rule of thumb, but deny it in a particular case if the costs exceeded the benefits even by a very small amount.

On this page, we include three discussions of the right to migrate:

- Joseph Carens’ deduction of the right to migrate from Robert Nozick’s minarchist state principles.

- Walter Block’s argument.

- Nathanael Smith’s theory of the streets.

Is the right to migrate a separate right at all?

In a blog post titled Moral Relevance of Countries Bleg, Open Borders: The Case, May 13, 2013, Sebastian Nickel argues:

The idea, as I understand it, is that the onus is on Michael Huemer to establish the existence of a Universal Human Right To Immigrate To The US. (Thomas Sowell expresses apparently the same view here.) This task seems hopeless, as the idea of a “Universal Human Right To Immigrate To The US” seems ridiculous. I agree that it seems ridiculous, but not because I do not think that people are generally within their (moral) rights to move to the US. I also think it would seem ridiculous to posit a Universal Human Right To Ride A Bicycle On A Tuesday, even though people generally are well within their rights to do so. We simply do not normally talk of moral rights to actions with specific, morally irrelevant features. (Compare this point with the 9th amendment to the US Constitution; HT: Vipul.) Given that I see no good reason for considering countries morally relevant in such matters, I contend that all that is needed is a right to rent property and to accept a job, and that the burden of proof is on restrictionists to establish that the geographical location of the property or of the work environment nullifies this right.

In this view, then, there is no need to articulate a particular right to migrate. However, a number of people have nonetheless tried to spell out how the right to migrate stems from basic principles of liberty.

Interpretation of Nozickean minarchist state principles by Joseph Carens

Robert Nozick was a libertarian philosopher known for the book Anarchy, State and Utopia, where he argues for the existence of a minimal night-watchman state whose only legitimate function is the protection of people’s natural rights. In a paper titled Aliens and Citizens: The Case for Open Borders, Joseph Carens argues, in a section titled Aliens and Property Rights:

Would this minimal state be justified in restricting immigration? Nozick never answers this question directly, but his argument at a number of points suggests not. According to Nozick the state has no right to do anything other than enforce the rights which individuals already enjoy in the state of nature. Citizenship gives rise to no distinctive claim. The state is obliged to protect the rights of citizens and noncitizens equally because it enjoys a de facto monopoly over the enforcement of rights within its territory. Individuals have the right to enter into voluntary exchanges with other individuals. They possess this right as individuals, not as citizens. The state may not interfere with such exchanges so long as they do not violate someone else’s rights.

Note what this implies for immigration. Suppose a farmer from the United States wanted to hire workers from Mexico. The government would have no right to prohibit him from doing this. To prevent the Mexicans from coming would violate the rights of both the American farmer and the Mexican workers to engage in voluntary transactions. Of course, American workers might be disadvantaged by this competition with foreign workers. But Nozick explicitly denies that anyone has a right to be protected against competitive disadvantage. (To count that sort of thing as a harm would undermine the foundations of individual property rights.) Even if the Mexicans did not have job offers from an American, a Nozickean government would have no grounds for preventing them from entering the country. So long as they were peaceful and did not steal, trespass on private property, or otherwise violate the rights of other individuals, their entry and their actions would be none of the state’s business.

Does this mean that Nozick’s theory provides no basis for the exclusion of aliens? Not exactly. It means rather that it provides no basis for the state to exclude aliens and no basis for individuals to exclude aliens that could not be used to exclude citizens as well. Poor aliens could not afford to live in affluent suburbs (except in the servants’ quarters), but that would be true of poor citizens too. Individual property owners could refuse to hire aliens, to rent them houses, to sell them food, and so on, but in a Nozickean world they could do the same things to their fellow citizens. In other words, individuals may do what they like with their own personal property. They may normally exclude whomever they want from land they own. But they have this right to exclude as individuals, not as members of a collective. They cannot prevent other individuals from acting differently (hiring aliens, renting them houses, etc.)…

Walter Block’s argument

In a paper titled A Libertarian Case For Free Immigration, Walter Block outlines in detail why he thinks that, per libertarian principles, emigration, migration, and immigration should all be free. Here are some important segments from Block’s argument:

[I]mmigration across national boundaries should be analyzed in an identical manner to that migration which takes place within a country. If it is non-invasive for Jones to change his locale from one place in Misesania to another in that country, then it cannot be invasive for him to move from Rothbardania to Misesania. Alternatively, if migration across international borders is somehow illegitimate, this should apply to the domestic variety as well.

As long as the immigrant moves to a piece of private property whose owner is willing to take him in (maybe for a fee), there can be nothing untoward about such a transaction. This, along with all other capitalist acts between consenting adults, must be considered valid in the libertarian world. Note that there is no freedom of movement of the person per se. This is always subject to the willingness of property owners in the host nation to accept the immigrant onto their land. [..]

In real world countries, certainly including the U.S., there can be found thousands, if not millions, of landowners willing to sell or rent space to people from all parts of the globe, no matter how obscure. For example, restaurateurs specializing in the foods common to foreign lands may wish to hire authentic foreign-born cooks. As a practical matter, it is inconceivable that some citizen property owners, whose families themselves immigrated in the past, would not be interested in taking in their countrymen, particularly at the very high remuneration available if most landlords do not wish to deal with the immigrants.

The case is equally clear for allowing immigrants to settle on unowned land. When there is virgin territory, there is no legitimate reason for immigrants (or domestic citizens) to be prevented from bringing it into fruitful production.

Nathanael Smith’s theory of the streets

Another version of the argument is due to Nathanael Smith. Smith develops a moral philosophy in his book Principles of a Free Society (Amazon ebook link). A shorter version of his argument is in this online article for TCS Daily. A few key aspects of his moral philosophy are outlined below:

- Smith makes a distinction between rights (negative rights) and liberties (which are a form of positive rights). His use of the terminology differs from that of some other libertarians. He argues that rights are rights to freedom from attacks on one’s life. He identifies habeas corpus and freedom of conscience as two fundamental principles from which rights can be derived. Liberty means a freedom to do anything so long as it does not infringe on people’s rights. Thus, the only legitimate reason for denying liberties is that it violates rights. Thus, I don’t have a “right” to swing my fist in the air, but I have the liberty to do so — unless your nose is in the area that I want to swing my first in.

- Smith also develops a theory of ownership of roads and other public resources, which is key to rebutting claims of collective property rights. His argument is that people in one region can choose to build, or close down, roads by collective decision making at the regional level, without consulting others. Outsiders may have no say in whether roads are built, or how they are arranged. However, once the roads are built and operational, they do have non-exclusive transit rights in those roads, and they cannot be arbitrarily forbidden from using those roads. Put another way, outsiders have the “liberty” to use the roads.

- Immigration restrictions are similar to denying outsiders the liberty to use the roads.

Some quotes from Smith’s book:

The general liberty to use the streets therefore has a basis in natural rights, applies equally to citizens and non-citizens of a state, and cannot be justly restricted by a government except when the streets are used in ways that constitute an objective danger to its citizens’ safety (e.g., drunk-driving, gang-warfare, or the transportation of hostile armies). Illegal immigrants are (at least in some cases) conducting a form of civil disobedience against an unjust law. It is the law, not the immigrant, which is in the wrong, and the law should be changed, rather than the immigrant removed.

Smith, Nathanael. Principles of a Free Society (Kindle Locations 2689-2693). The Locke Institute. Kindle Edition.

Smith also makes an appeal to the founding mythologies of the United States:

First, the Statue of Liberty, a gift to the United States from France dedicated in 1886, which in the late 19th century was the first sight that immigrants arriving in New York by sea saw in the New World, still stands in New York harbor and bears a plaque with a poem, “The New Colossus,” that has come to represent the meaning of the statue. The poem runs: Not like the brazen giant of Greek fame, With conquering limbs astride from land to land; Here at our sea-washed, sunset gates shall stand A mighty woman with a torch, whose flame Is the imprisoned lightning, and her name Mother of Exiles. From her beacon-hand Glows world-wide welcome; her mild eyes command The air-bridged harbor that twin cities frame. “Keep, ancient lands, your storied pomp!” cries she With silent lips. “Give me your tired, your poor, Your huddled masses yearning to breathe free, The wretched refuse of your teeming shore. Send these, the homeless, tempest-tossed to me, I lift my lamp beside the golden door!” Based on its immigration policies today, America is unworthy to take pride in the Statue of Liberty and in what, thanks to this poem and the immigrant experience at Ellis Island, it has come to represent. Not only does America shut out most foreigners who want to come, but it deliberately discriminates in favor of the affluent and educated, and against just those whom, in the poem, the Statue of Liberty welcomed: the poor, the homeless, the wretched, the desperate. Yet Americans have not commissioned a couple of tugboats to drag the Statue of Liberty into the sea. We have not even chiseled away “The New Colossus” from the Statue of Liberty’s walls. Americans still revere the Statue of Liberty as a national symbol, and even cite the Statue of Liberty poem with a patriotic pride, weirdly unmixed with shame, at how far we have departed from the ideal it so beautifully expresses. The Statue of Liberty today holds a position in America’s national psyche similar to that which the Declaration of Independence held in the times when slavery and segregation mocked the brave manifesto that “all men are created equal and endowed with their Creator with … inalienable rights.” We love it, we take pride in it, we would hardly know who we are supposed to be as a nation without it. Yet we do not live by it, paying a certain price in cognitive dissonance and self-deceit for our hypocrisy; and we may someday find it in ourselves to return to it; yet there is bitter resistance to any such plan.

Smith, Nathanael (2010-12-10). Principles of a Free Society (Kindle Locations 2766-2786). The Locke Institute. Kindle Edition.

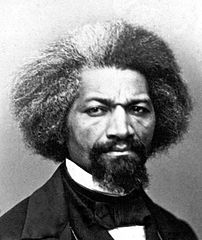

The photograph featured at the top of this post is of Frederick Douglass, an advocate of the right to migrate.

17 thoughts on “Right to migrate”

Comments are closed.