I’ve suggested before that although the US Republican Party’s position amongst immigrant communities in the US seems weak, that is not reason to assume this will always be the case for the foreseeable future. I recently stumbled across an interesting 2010 profile of Jason Kenney, the Conservative politician who currently is the Canadian Minister of Citizenship, Immigration, and Multiculturalism. (If you are having a hard time imagining that a Republican could ever fill an equivalently-titled office in the US, perhaps you have a clue as to why the GOP finds it so hard to penetrate immigrant communities.)

Kenney first assumed responsibility for immigrant outreach in 2006. He found that although he was able to cite numerous Conservative policy successes that helped immigrants settle in Canada, this wasn’t convincing to immigrant voters. As it turns out:

“‘You’re a community with famously conservative values. Incredibly hard-working. Entrepreneurial, devotion to family, intolerant to criminality. These sound like our values. Conservative values.'” Why, he asked, weren’t Korean Canadians already turning to the Conservatives?

“One of the guys around the table was the president, believe it or not, of something called the Korean Canadian Evangelical NDP Small Businessmen’s Association. My jaw just about hit the floor. It sounded like the association of the hens for the fox, right?”

What had happened, the guy said, was that when a lot of Koreans settled in Burnaby, B.C., in 1972, there was a New Democrat MP who was simply good at showing up to churches and community events. He helped people with their immigration case files. People got to know him. So when that MP retired and his constituency assistant who’d worked on immigration files inherited the NDP nomination, the Korean evangelical businessmen gave her their support. And so on ever after.

“Thirty-five years of voting history established by a relationship!” Kenney said now, still marvelling. “And the light went off for me. How incredibly important relationships are. It’s blindingly obvious, but for newcomers those initial relationships that they establish are hugely important.”

Sure, these things are symbolic. But as economist Robin Hanson says, politics is not about policy. In a democracy, our elected officials not only govern, but represent us. Say it with me: we vote for people who represent us. As Kenney found, if you don’t even reach out to someone, why would they ever think that you want to represent them? So today, Kenney’s Twitter account is a litany of cultural events:

“Hosted a town hall meeting in Montreal’s Chinatown on how best to combat immigration marriage fraud.” “Had a great encounter with the large & enthusiastic congregation of Notre Dame des Philippines.” “Did roundtable with folks from the Egyptian, Pakistani, Iraqi & other communities to encourage their participation in the PSR [private sponsorship of refugee] program.” “Did a great event with the Montreal Afghan community in support of the superb Conservative candidate in St. Lambert, Qais Hamidi.” “Had one of the best meals I can remember at the Khyber Pass restaurant in Montreal, together with Afghan friends. Highly recommended!”

How easy is it to imagine a similar flurry of Tweets from a Republican politician? (Of course, with US Republicans, their approach to outreach is a little worse than benign neglect: as Muslim blogger Rany Jazyerli has observed, in recent times whenever Republicans have been bragging about attending a Muslim community event, it’s because — to put it politely — they were there to cast doubt on Muslims’ loyalty to the US.)

Of course, Kenney and Conservative Prime Minister Stephen Harper haven’t been just coasting on doing some goodwill tours — they have proven they walk the talk on immigration policy:

In power they moved quickly to produce legislative change that could prove their bona fides. They cut in half the $975 immigrant right-of-landing fee, introduced by the Chrétien Liberals in 1995 as a deficit-fighting measure, in their first year in office.

They eliminated visa requirements for visitors from eight formerly Communist countries in Europe. Skyrocketing refugee claims from the Czech Republic’s Roma population made Kenney reintroduce visa requirements for that country a year later, but he still counts the move as a net gain. So do many Eastern European Canadians. Wladyslaw Lizon, former head of the Canadian Polish Congress, will be running for the Conservatives in Mississauga East-Cooksville in the next election.

Kenney has also pursued some less liberal measures: some other initiatives of his include restructuring the Canadian skilled worker immigration programme (liberalising in some areas, restricting in others), and pursuing some arbitrary immigration policies (notably, defending his use of discretion to keep British MP George Galloway out of Canada on very tenuous grounds). That he is not an open borders advocate does not make his accomplishments any less impressive, or instructive.

Meanwhile, the same publication which profiled Kenney in 2010 recently did another story on him, with more background behind how he came to be responsible for immigrant outreach, dating back to when, as a 26-year-old activist in 1994, he told Stephen Harper that demographic destiny demanded that the Conservatives, as a matter of survival, win over immigrant communities. This second profile also has more interesting details on Kenney’s immigration policy views, and anecdotes of his continued ability to win over immigrants by understanding how to communicate with them:

- Advertise in their media, ideally timing to coincide with events with cultural significance like the Cricket World Cup;

- Learn to speak their languages: the article suggests Kenney has learnt enough Punjabi to understand when a speech is promoting political extremism;

- And as their representative, recognise what’s important to them: Kenney led the initiative to apologise for past government abuse of Chinese immigrants, and also sought government recognition of certain genocides.

Small things in the greater scheme of it all, but as Kenney’s former chief of staff says: “It might not seem important to the majority of the population, but for the concerned communities, it’s huge.”

There are conceivable reasons to doubt the Republicans can pull off a similar feat as Kenney and the Canadian Conservatives. Some skeptics argue the Conservatives of Canada are barely, if at all, to the right of Democrats in the US. It’s plausible that the median immigrant voter will be more right-leaning than the median Democratic politician, but much much more left-leaning than the median Republican politician. But until the Republicans stop denigrating immigrant communities and start reaching out to them, until they can find their Jason Kenney, it seems rather early to declare that it is all but impossible for them to win over the immigrant vote.

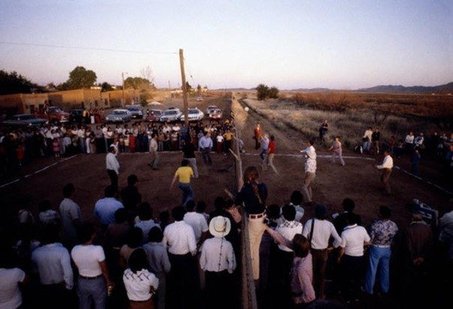

The photo of Jason Kenney in the header of this post is owned by the Policy Exchange, and used under the Creative Commons Attribution licence.