I occasionally hear people linking gay marriage and open borders. Thus, Jose Antonio Vargas (whom I wrote about here and here) says:

We are fighting for more than immigration reform. We are fighting for the dignity of people and liberation. More than anything Define American is trying to change media and culture. Again, LGBT rights would not have happened without culture shifting.

And Charles Kenny, in “Why Immigration is the New Gay Marriage,” writes:

The evolution of public attitudes toward gay marriage—which a majority of Americans now support—demonstrates that cultural shifts can be dramatic and rapid when circumstances are right. Perhaps U.S. citizens will start realizing that more people aspiring to become Americans is no threat to the institutions of America, just as they have come to accept that more people wanting to get married—some to people of the same sex—is no threat to the institution of marriage.

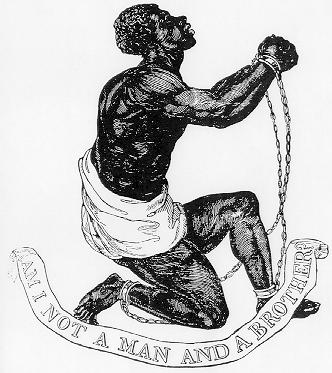

I’ll explain in a follow-up post why I don’t think open borders can expect to get much benefit from riding the coattails of, or emulating, the gay marriage movement. First, I want to describe the historical movement that open borders does resemble, and which it should emulate, namely: the movement to abolish slavery.

An excellent short history of the abolition of slavery, in Chapter 5 of his book For the Glory of God by sociologist Rodney Stark, which correctly treats it as part of the history of Christian social justice, begins with a sad history of this deplorable institution, which “has… been a nearly universal feature of ‘civilization’ [and] was also common in a number of ‘aboriginal’ societies that were sufficiently affluent to afford it– for example, slavery was very prevalent among the Northwest Indians,” and which, in fact, before the advent of Christian social justice, essentially occurred wherever “the average person can produce sufficient surplus that it becomes profitable for someone to own him or her” (Stark, p. 292-293). Stark describes slavery among the Northwest Coast Indians; in classical Greece and Rome; in the Muslim world; in black Africa long before the Atlantic slave trade; and in the New World in modern times. Stark pays less attention to China– space is limited, after all– but slavery also existed there.

The Bible doesn’t condemn slavery, though the Mosaic law does greatly ameliorate it:

Although Jews were prohibited from enslaving their fellow Jews, and their slaves therefore came from among the “heathen,” there were still severe limits on their treatment. Death was decreed for any Jewish master who killed a slave. The Torah admonished that freedom was to be awarded any slave as compensation for suffering acts of violence: “And if a man smite the eye of his servant, or the eye of his maid, that it perish; he shall go free for his eye’s sake. And if he smite out his manservant’s tooth, or his maidservant’s tooth; he shall let him go free for his tooth’s sake” (Exodus 21:26-27). Hebrew law held that children of slaves must not be parted from their parents, nor a wife from her husband. Moreover, in Deuteronomy 23:15-16 Jews were admonished not to return escaped slaves: “Thou shalt not deliver unto his master the servant which is escape from his master unto thee: he shall dwell with thee, even among you… thou shalt not oppress him.” (Stark, p. 328)

Is it embarrassing that God condones slavery in the Mosaic Law? In such cases, one must be careful not to kick away the ladder by which we ascended. Christians believe that God is trying to redeem fallen mankind. That sometimes means meeting fallen man where he is at a given time, improving him by small steps, and condoning much that is defective with respect to loftier ethical standards that he may attain later. Compared to the brutal exploitation of slaves by so many other civilizations, slavery as prescribed in the Mosaic law is humane. Jesus later told the Pharisees that Moses had permitted men to divorce their wives “because of the hardness of your hearts” (Matthew 19:8), and I think (and more importantly, Christians have long held) that the same principle applies to much of the Mosaic law. It was a kind of compromise between ethical perfection and human weakness. The subsequent history of the Jews shows how little they were able even to live up to this limited standard. But in the teachings of Jesus the fullness of ethical perfection was revealed, and this rendered obsolete some of the rituals and minor rules, and especially the imperfections and compromises, of the Mosaic law.

Yet even in the New Testament, slaves are told to obey their masters by both St. Peter– see 1 Peter 2:18— and St. Paul– see Ephesians 6:5 and Colossians 3:22. I don’t find these passages troubling, because I see them as instances of Jesus’s teaching to “turn the other cheek” (Matthew 5:39) and, in general, to submit to coercion and even give more than what is demanded: “If anyone forces you to go one mile, go with them two miles” (Matthew 5:41). After all, if we ought to serve our fellow men, then why should it be an unmitigated evil to be legally bound to serve one of our fellow men? More troubling, possibly, is that in advising the Ephesians, St. Paul does not command Christian masters to manumit their slaves, saying only “And masters, do the same things [i.e., render sincere service] to them [i.e., to your slaves], and give up threatening, knowing that both their Master and yours is in heaven, and there is no partiality with Him” (Ephesians 6:9). Certainly for masters to serve their slaves and to stop threatening them is a step in the right direction, but how can any kind of slavery, even an ameliorated form, be compatible with the Gospel of love?

I would offer three defenses of St. Paul here. First, the apostles weren’t trying to make a secular political revolution, for which they didn’t have the strength, but to save souls, to work a moral transformation from within. Had they attempted to launch a revolution against slavery, the Roman Empire would have crushed them. Even semi-public exhortations to manumission in letters to churches might have been dangerous. Second, this is another case of God meeting us where we are, and not giving us moral standards we’re not yet ready to live by. What would masters in the early Ephesian church have done, had St. Paul commanded them to manumit all their slaves? Let’s assume it would have been good for their souls as well as their slaves if they had obeyed. But, perhaps they would not have obeyed, but left the church instead. Would that justify Paul in limiting his exhortations to good treatment rather than manumission? I think so. Third, what happens to a manumitted slave? Don’t think of the ancient Roman Empire as a modern capitalist economy where any random person can find a job and support himself. A typical slave would probably have trouble making it on his or her own. To urge masters to manumit their slaves into isolation and destitution might have been no mercy. The slaveless society was a social model yet to be developed.

Theologian David Bentley Hart describes (in his book Atheist Delusions: The Christian Revolution and its Fashionable Enemies, pp. 176ff.) the attitudes of the early Church fathers towards slavery…

The attitudes of many of the fathers of the church toward slavery ranged from (at best) resigned acceptance to (at worst) a kind of prudential approval. All of them regarded slavery as a mark of sin, of course, and all could take some comfort in the knowledge that, at the restoration of creation in the Kingdom of God, it would vanish altogether. They even understood that this expectation necessarily involved certain moral implications for the present. But, for most of them, the best that could be hoped for within a fallen world (apart from certain legal reforms) was a spirit of charity, gentleness, and familial regard on the part of masters and a spirit of longsuffering on the part of servants. Basil of Caesarea found it necessary to defend the subjection of some men to others, on the grounds that not all are capable of governing themselves wisely and virtuously. John Chrysostom dreamed of a perfect (probably eschatological) society in which none would rule over another, celebrated the extension of legal rights and protections to slaves, and fulminated against Christian masters who would dare to humiliate or beat their slaves. Augustine, with his darker, colder, more brutal vision of the fallen world, disliked slavery but did not think it wise always to spare the rod, at least not when the welfare of the soul should take precedence over the welfare of the flesh. Each of them knew that slavery was essentially a damnable thing– which in itself was a considerable advance in moral intelligence over the ethos of pagan antiquity– but damnation, after all, is reserved for the end of time; none of them found it possible to convert that eschatological certainty into a program for the present… Given the inherently restive quality of the human moral imagination, it is only natural that certain of the moral values of the pagan past should have lingered on so long into the Christian era, just as any number of Christian moral values continue today to enjoy a tacit and largely unexamined authority in minds and cultures that no longer believe the Christian story.

It is in this context that a certain stunning insight occurred to a certain 4th-century theologian, Gregory of Nyssa, to whom, as far as I can tell, the abolition of slavery may be traced.

And yet– confusingly enough for any conventional calculation of history probability– there is Gregory of Nyssa, Basil’s younger and more brilliant brother, who sounded a very different note, one that almost seems to have issued from some altogether different frame of reality. At least, one searches in vain through the literary remains of antiquity– pagan, Jewish, or Christian– for any other document remotely comparable in tone or content to Gregory’s fourth sermon on the book of Ecclesiastes, which he preached during Lent in 379, and which comprises a long passage unequivocally and indignantly condemning slavery as an institution. That is to say, in this sermon Gregory does not simply treat slavery as an extravagance in which Christians ought not to indulge beyond the dictates of necessity, nor does he confine himself to denouncing the injustices and cruelties of which slaveholders are frequently guilty. These things one would naturally expect, since moral admonitions and exhortations to repentance are part of the standard Lenten repertoire of any competent homilist. Moreover, ever since 321, when Constantine had granted the churches the power of legally certifying manumissions (the power of manumissio in ecclesia), propertied Christians had often taken Easter as an occasion for emancipating slaves, and Gregory was no doubt hoping to encourage his parishioners to follow the custom. But if all he had wanted to do was recommend manumission as a spiritual hygiene or as a gesture of benevolence, he could have done so quite (and perhaps more) effectively by using a considerably more temperate tone than one actually finds in his sermon. For there he directs his anger not at the abuse of slavery but at its use; he reproaches his parishioners not for mistreating their slaves but for daring to imagine that they have the right to own other human beings in the first place.

One cannot overemphasize this distinction. On occasion, scholars who have attempted to make this sermon conform to their expectations of fourth century rhetoric have tried to read it as belonging to some standard type of penitential oration, perhaps rather more hyperbolic in some of its language but ultimately intended to do no more than impress the consciences of its hearers with the need for humility… [But] Gregory’s language in the sermon is simply too unambiguous to be read as anything other than what it is. He leaves no room for Christian slaveholders to console themselves with the thought that they, at any rate, are merciful masters, generous enough to liberate the occasional worthy servant but wise enough to know when they must continue to exercise stewardship over less responsible souls. He certainly could have done just this; he begins his diatribe (which is not too strong a word) with a brief exegetical excursus on a single, rather unexpectional verse, Eccesiastes 2:7 (“I got me male and female slaves, and had my home-born slaves as well”); a text that would seem to invite only a few bracing imprecations against luxuriance and sloth, and nothing more. As he warms to his theme, however, Gregory goes well beyond this…

Continue reading What Open Borders Can Learn from the Abolition of Slavery