David Goodhart, a British writer and thinker, has some interesting thoughts on the interplay between immigration, multiculturalism, and policy. I think he does a great job of pointing out some problems with traditional approaches to multiculturalism, and how the left is often too blithe about the problems that living in a plural society can create. However, early on in the interview, he makes some comments that I find questionable. The first is where he quite rightly calls out immigration liberals for making unrealistic assumptions:

In a nutshell, what is the historical context of today’s multicultural Britain?

Britain had an open door policy from 1948 to 1962, when anybody from the empire or Commonwealth could come and live in Britain. That is essentially saying to some 600 million people around the world, most of them from the working classes or the peasantry, that there are no restrictions on their entry. Which was a magnificent idea, but also a bit of a disaster. Those who framed the legislation thought that no-one would come, but they did – half a million came between ’48 and ’62, albeit a small number compared to today’s figure.

Which is over half a million during the last year alone.

Yes, in terms of inflow – although there is also quite a bit of outflow. We had a parallel situation two generations later in the early 2000s, with Eastern Europeans coming to Britain from the EU. Only 15,000 were meant to come, but in reality a much larger number did.

Yes, the liberals were wrong in their estimates of how many would come. But how wrong were they about the harmful impacts of immigration? Did the UK economy collapse because hundreds of thousands instead of tens of thousands came under the EU’s open borders? This is an obvious question, but it’s left undiscussed. The casual assumption is that lots of immigrants are obviously harmful, and the interviewer does not challenge this. Goodhart explains in theoretical terms why he believes they are harmful, citing Robert Putnam’s work on social capital, but he never points to concrete instances of harm from European immigration, nor does he explain a clear causal mechanism for how lower immigrant inflows would have facilitated assimilation.

Moreover, it’s taken for granted that Putnam’s research (assuming it is correct in finding that diversity has undermined social capital in the US) is easily generalisable to other contexts. Abdolmodhammad Kazemipur attempted to reproduce Putnam’s research in Canada, and actually found the opposite: Canadian communities with greater diversity have more social capital than their homogeneous counterparts.

Goodhart makes an interesting point that historically, Britain has pursued a “light touch” when it comes to integrating non-British into its society, citing its approach to colonial governance. I’m not sure how true this is, however: in past centuries the UK had little trouble integrating Huguenot refugees or other European immigrants, even though they initially formed ethnic enclaves of their own. Goodhart makes a fair point that UK policymakers did in fact make some false assumptions about assimilation in the era of Commonwealth open borders: to my knowledge, it is true that contemporarily many people erroneously assumed the working class Briton would embrace his Commonwealth peers from Asia and the Caribbean. Stories abound of Caribbean immigrants entering the UK only to be astonished to find that although they considered themselves British, the Britons did not think the same.

Once we’ve breezily assumed that immigration must by definition reduce social capital, and assumed that this reduction in social capital outweighs all the relevant benefits of immigration (Goodhart does not clearly spell out how he is performing this cost-benefit analysis), the obvious conclusion is to reduce immigration levels:

What is to be done?

I think levels of immigration must be reduced. I certainly favour a cap, although it’s a little arbitrary and difficult to manage. But we also need to relearn how to encourage people to join in. We need to develop better ideas of integration and of what it is to be a British citizen, particularly in areas with high immigration settlement like Tower Hamlets in London, dominated by Bangladeshis, or Bradford in Yorkshire dominated by Pakistanis.

Britain has not set up patterns of residence, schooling and employment that make it easy for people to join in. Certain groups that have the cultural resilience do join in and often flourish, even if they often remain residentially segregated. But other groups tend to live separately in all areas of life, and have reproduced many of the institutions of their home country in England.

If the problem is with integration policy, why not fix integration policy? Arbitrarily forcing people to stay out of the UK is by definition incredibly harmful to all these immigrants, as any exercise of government coercive force would be. As Goodhart concedes, it is also incredibly difficult to implement. I find it particularly galling that Goodhart so breezily assumes away the problems of coercion and arbitrariness in capping immigration that he feels he should spend most of his time dwelling on integration policy instead. If immigration liberals have been too blithe in their assumptions about assimilation or quantifying immigration, this shows incredible blitheness about the injustice and difficulties involved with arbitrarily restricting immigration.

I link to this interview because I think Goodhart has interesting ideas about the challenges of integrating immigrants into British society. Many of his recommendations seem sensible. But I find it interesting that an otherwise sensible person makes so many blithe assumptions of his own about the impact of immigration, and casually embraces arbitrary use of government force against prospective immigrants. The most dangerous assumptions tend to be the ones we don’t even realise we are making.

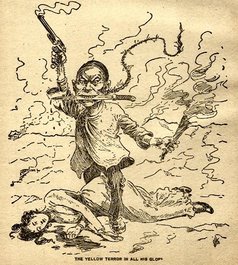

The cartoon featured in the header of this post dates to 1899, and depicts a Chinese man who has murdered a white woman. The original caption reads: “The Yellow Terror in all his glory.”