Donald Dobkin is a Canadian-American immigration lawyer who, a few years back, authored a Georgetown Immigration Law Journal article titled Challenging the Doctrine of Consular Nonreviewability in Immigration Cases. The whole article is worth reading, but the short story is:

- US consular officers are entitled to deny you a non-immigrant visa if you cannot prove to them you won’t immigrate to the US

- Because this is considered a question of fact, under US law, this decision cannot be questioned or overturned, not even by the Secretary of State or the President

- Courts have held that under very limited circumstances, they can review non-factual issues that affected the visa application outcome

- However, the end result is that for the vast majority of people refused a non-immigrant visa to the US, there is no appeal mechanism and no check on US consular officers’ power to disrupt or destroy foreigners’ lives

One interesting thing I learned is that the doctrine of consular nonreviewability (sometimes mockingly called consular absolutism; John Lennon supposedly once referred to US consular officers as “absolute monarchs”) has its roots in the 1889 case Chac Chan Ping v. United States (often simply called the Chinese Exclusion Case). This is the case which first held that the government has the right to do whatever it likes to foreigners trying to enter the US, for whatever reason. Consequent immigration law doctrine in the US has built on the foundation of the Chinese Exclusion Case, especially in the area of consular nonreviewability. As Dobkin quotes one scholar saying:

Reliance on the Chinese Exclusion Case is a bit like reliance on Dred Scott v. Sandford or Plessy v. Ferguson. Although the Supreme Court has never expressly overruled the Chinese Exclusion Case, it represents a discredited page in the country’s constitutional history.

(For non-Americans, Dred Scott and Plessy v. Ferguson are two famous US Supreme Court cases which respectively held that black people have no rights and that racial segregation is constitutional.)

Immigration law’s roots in racism go deep. Beyond the US, virtually every modern Western country rooted in the common law tradition originally adopted immigration controls in order to exclude foreigners from the wrong racial backgrounds. See for instance the UK closing its borders to Commonwealth citizens because they received too many black and Asian immigrants, Australia adopting a “White Australia” legal regime to keep out Asian immigrants, or Canada pursuing immigration controls in the 19th century to restrict Chinese immigration.

And the best traditions of immigration law continue today. In Olsen v. Albright, former US consular officer Robert Olsen sued the State Department for wrongful dismissal after he refused to enforce a visa policy that discriminated against people who “look poor” or were born into the wrong race. Given how well-documented the racist nature of State’s visa policy was, the judge had no choice but to agree with Olsen — but given the doctrine of consular nonreviewability, he had no power to overturn the denial of visas to anyone who, as one visa refusal documented, “Looks + talks poor.”

Dobkin notes that in many European countries, including Germany, judicial review of visa decisions is enshrined in law. The catastrophic effects which US judges and consular officers fear from permitting judicial review have not materialised. Dobkin suggests that this is because:

- Pursuing judicial review is costly, so applicants will only pursue it if they strongly believe the consular officer was wrong

- More importantly, the risk of facing judicial review forces consular officers to get visa decisions right

One interesting point Dobkin highlights is that unfortunately for foreigners, immigration law cases tend to be decided precisely when anti-immigrant sentiment runs high: you get a lot more immigration lawsuits when immigration law enforcement is at its peak. This bias means that immigration legal precedents favourable to immigrants are relatively rare, and likely accounts for the long survival of the Chinese Exclusion Case.

There are of course rare instances where the courts do decide to review a consular officer’s decision, and Dobkin cites quite a few. These are worth a separate post, which I will publish in due time. But they do not materially change the picture: US immigration policy enthrones consular officers as dictators, capable of punishing people for reasons as trivial as wearing the wrong coat or being from the wrong ethnic origin. Not even the President or Supreme Court can overturn their decision. And there is no real reason for this, except for the US immigration legal system’s peculiar attachment to consular nonreviewability, a doctrine rooted in racism, and one that plenty of other developed countries are fine doing without.

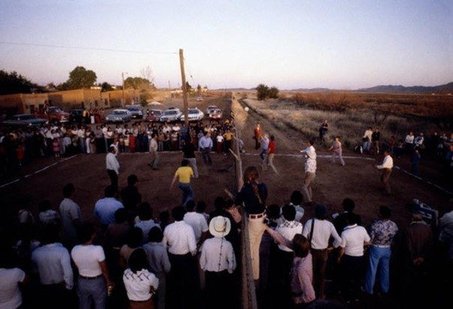

The painting featured at the top of this post depicts the deportation of Acadians from Canada in 1755.