This post is part of a series by Justin Merrill describing his personal experience with immigration and his embrace of open borders. It is part of our ongoing series of posts that are based on personal anecdotes. The first post in the series is here.

I was a senior in high school when terrorists attacked on September 11, 2001. I was at a critical point in deciding what to do after graduation and decided to enlist in the Marine Corps. I went to boot camp one year after 9/11. After I finished my combat and job training, I was sent to my first duty station in Okinawa, Japan. My time in Okinawa was bittersweet because our command was really strict and paternalistic and my office made me work incredibly long hours. But unlike many of my peers, I made an effort to soak up the culture and experience more of the off-base life than just bars. As mentioned in my previous post, I was raised around Japanese exchange students and I also did karate as a kid, so my starting level of Japanese was basic, but higher than most (counting and common phrases).

Eri, my future wife, and I met and started chatting through Yahoo Messenger in 2003. She is from Toyota, Japan (yes, where they make the cars), which is on mainland Japan. Okinawa is a tropical island far to the south, sometimes called the “Hawaii of Japan”. Our relationship was more of a friendly pen pal nature, mostly because there wasn’t any expectation of meeting in the future. I also was opposed to having a serious relationship while in the Marine Corps because I saw how high the strain of military life is on relationships. My tour in Okinawa was only one year and a vacation to visit her wasn’t practical. Eri spoke English well because she was an exchange student in North Carolina for two years and studied English in Australia after graduating from high school. We kept in touch over the years and got to know each other pretty well. After my year in Okinawa, my final duty station was in the Washington, DC area for the remainder of my term. Even though I was raised on the west coast, I liked the DC area so much that I decided to stay there after I got out. I shared an apartment with my newlywed friends and was putting down roots on my terminal leave when Eri told me that she would be visiting her host family that she lived with while in North Carolina. I pointed out that the timing was perfect and that we should meet up. We agreed to spend three weeks together and instantly hit it off. A week after we met we decided to get married. We spent a week in NYC, a first for both of us, during Christmas and New Year’s and bought our wedding rings in the Diamond District. Our families were both very happy for us, but I didn’t want to do a shotgun wedding. I wanted to meet her family first and have the ceremony in Japan, especially since we are both Buddhist and Eri’s mom’s temple offered to perform the ceremony. So we arranged to have receptions in Toyota and Utah for both our families. The wedding was scheduled for February. Eri’s tourist visa would expire soon so she returned to Japan to start planning the wedding and I began looking for a new apartment in DC for us to move in to after the receptions.

Before our wedding, in order for our marriage to be recognized in the States, we had to get a marriage certificate from the US embassy consulate in Osaka, which is pretty far from Toyota. The only day that happened to fit in our busy schedule was Valentine’s Day. We chose against having the wedding on Valentine’s Day because it seemed too cheesy, but our marriage certificate states we were legally wedded on that day. Now we celebrate our anniversary on Feb. 14th and tell people we were “accidentally” married on that day. Only my mom could attend on my side of the family, but our wedding and reception in Japan were great. Her family helped pay for an extravagant celebration and all her friends and family came and supported us. It’s not common to marry a gaijin (foreigner) in Japan. After the wedding we had a honeymoon of sorts and stayed with Eri’s friends, Phil and Yukako, who attended our wedding and who were a couple like us (former Marine husband and Japanese wife). Eri was an exchange student in North Carolina with Yukako and they became best friends; it’s funny they would both marry Marines. Phil was working as a civilian on the Marine Corps Air Base in Iwakuni, which is far to the south. After spending time with them, Eri and I were to fly to Utah to prepare for our reception for my family.

For some reason, I think because I was using a Delta buddy pass, we had to fly on different flights and I arrived a couple days before her. Fortunately I bought ourselves new cell phones and added her to my plan before I left, since we were planning on living in the States. As I was on my way to pick her up in Salt Lake City she texted me that she wouldn’t be arriving and was being taken into custody. She had a layover and her port of entry was Minneapolis, MN. When she went through customs they were suspicious because she had recently visited the States. They searched her luggage and found wedding photos and deduced that she was trying to live in the US. They took her into custody and interrogated her for hours, even playing a good cop/bad cop routine, while I was standing at her terminal, horrified by the nightmare that was beginning. They denied her entry and put a flag on her passport so that she could not reenter the States until we went through the process and got her green card. We later discovered that this was incorrect; she would not be able to enter the country under any condition, something that would have been nice to know before we went through the entire process. Luckily we found a loop hole.

Eri was flown back to Japan through Holland. She spent over three days straight on an airplane without a chance to even shower. With only days until our reception, we were trying frantically on both ends to find a way to get her into the country. She went back to the embassy consulate in Osaka and I was contacting my representative and USCIS. Unfortunately there was nothing they could do. They said there was no discretion on this matter and no way to even allow her to temporarily visit for our reception. This close to the reception it was impossible to cancel. Her parents could attend and it was nice that our families could meet, but it was sad that it was under these circumstances. My mother-in-law served as a substitute bride and cut the cake with me. We made the best of the situation.

The stressful part would be to decide what to do next. Fortunately I wasn’t so rooted that I was able to sell off my belongings, cancel and get a refund on my deposit for our new apartment, and cancel our phone plan. I had to sell my recording studio (I started a record label) and back out of a real estate foreclosure deal that would have earned me $200k, but I couldn’t find a lawyer to be my agent while I was out of the country. I mailed the rest of my belongings to our friends, Phil and Yukako. We devised a plan where I could get a job on base before my tourist visa expires and the base would sponsor my visa and let me stay in Japan. I had to take the first job I could get and move up from there, but it was worth it. Eri and I got our own little house and started our new lives together in Iwakuni, Japan.

We both sacrificed a lot, but we just wanted to be together. We were young and naïve and didn’t even know we were breaking the law. We thought that getting a spouse visa was as simple as applying after you entered on a tourist visa (turns out that’s exactly how I did it in Japan). It’s not like she was intending to overstay her visa. We were so busy planning and traveling that we didn’t properly research and the immigrants I did consult immigrated to the US before 9/11 and their information was out of date. I was shocked how they treated Eri like a criminal or terrorist, she was only twenty years old and didn’t fit the profile. I was also surprised at how the policy overrode common sense. It was actually harder for Eri to enter the country because she was married to me. The immigration policy ended up costing us a lot of money, hardship, and productivity and career opportunities over the years, and I must say it felt unnecessary.

Here’s the next post in the series.

Some related background and links (added by our editorial team)

A United States visa does not guarantee entry into the United States. All it does is allow the holder to travel to the United States and present himself or herself at a port of entry. The officer at the port of entry has discretionary authority to deny admission if the officer suspects immigrant intent or other violations of the terms of the visa.

Nationals of about 50 countries (including Japan, where Eri was from) are eligible to enter the United States for short term business and pleasure trips through the Visa Waiver Program. VWP entries are treated similarly to entries made while on a B1/B2 visa. A person can be denied entry based on the VWP or B1/B2 visa if it transpires that the person intends to transition to a long-term non-immigrant or immigrant status. It is also not generally permissible for somebody in the US on VWP or B1/B2 travel to transition while within the United States to a long-term non-immigrant status (such as F student status or H-1B status) or immigrant status (that Eri would have been eligible for as the wife of a US citizen).

Some related reading on denial at a port of entry:

- Friend, relative, etc. denied entry to the U.S., U.S. Customs and Border Protection.

- DHS Traveler Redress Inquiry Program (DHS TRIP), United States Department of Homeland Security.

- At the U.S. Border or Airport: What to Expect When Entering. Entering the U.S. may not be easy, even with a valid visa in hand. (NOLO.com).

- A Tale of “Voluntary Departure” from the Comments by Bryan Caplan, EconLog, August 22, 2011, quoting Tim Worstall:

Having been caught up in the US system once “voluntary departure” is anything but.

On entering the country on a 10 year, multi-entry, business visa (I owned a small business in the US at the time) immigration officials decided that I should not be allowed to enter.

I was not allowed legal representation of any kind. I was interviewed and then the notes of the interview were written up afterwards (ie, what the officer remembered he and I had said, not what was actually said).

I refused to sign such misleading notes. I was told that if I did not I would be deported, my passport declared invalid for travel to the US for the rest of my life.

So of course I signed and then made my “voluntary departure” which included being held in a cell until the time of my flight, being threatened with being handcuffed while going to the flight and the return of my passport only upon arrival in London.

My 10 year multi entry visa had of course been cancelled. My attempts to get matters sorted out, so that I could visit my business, were rather hampered by the way that the interview notes which I had signed under duress were taken to be the only valid evidence by the INS (as was) that should be discussed when deciding upon visa status.

I lost the business and haven’t bothered returning to the country in the more than decade since.

There is no law, evidence, representation nor even accurate recording of proceedings in such “voluntary departures”. It is entirely at the whim of the agents at the border post. I was actually told by one agent “I’m gonna screw you over”.

Something of a difference from what’s scrawled over that statue in New York really. And I’m most certainly not the only business person this sort of thing has happened to.

Some other general reading:

- Visa versus authorized stay: why can you not renew your visa in the United States? by Vipul Naik, Open Borders: The Case, December 30, 2014.

- An addendum to visa versus authorized stay: “automatic visa revalidation” by Vipul Naik, January 5, 2015.

UPDATE: Victoria Ferauge, who has previously written a guest post for the site, wrote a post on her personal blog titled A US Immigration Tale commenting on the story:

In the last paragraph of his post I can hear his bitterness at how his wife was treated.

We were young and naïve and didn’t even know we were breaking the law. We thought that getting a spouse visa was as simple as applying after you entered on a tourist visa (turns out that’s exactly how I did it in Japan). It’s not like she was intending to overstay her visa. We were so busy planning and traveling that we didn’t properly research and the immigrants I did consult immigrated to the US before 9/11 and their information was out of date. I was shocked how they treated Eri like a criminal or terrorist, she was only twenty years old and didn’t fit the profile. I was also surprised at how the policy overrode common sense. It was actually harder for Eri to enter the country because she was married to me.

And as I read this I was amazed at how things had changed in just a few short years. Pre-911 my French husband got his Green Card in Seattle. He had landed in the US on one kind of visa and it was just a matter of going down to immigration and filling out the paperwork to get residency status based on his marriage to me, l’américaine. Very simple. No one at immigration so much as blinked twice when we explained what we wanted. The final interview lasted less than 10 minutes. That’s all it took for the very pleasant official to decide that my husband merited a Green Card.

We were just as naive as Merrill and his wife. We took for granted that because we were married, we could choose which country we wanted to live in. And our assumptions proved true at that time.

In this story we can see how a vigorous and punctilious application of immigration law can hurt not only the immigrant but the native citizen as well. Please note that the US not only lost an immigrant, but they forced one of their own into emigrating. Merrill and his wife didn’t get to choose where they wanted to live – they were forced in the direction of the country that would take both of them.

Interestingly enough, that turned out to be Japan – a country that many Americans consider to be unfriendly to immigrants.

Oh, the irony…

UPDATE 2: The post was picked up by MetaFilter and got 34 comments there. Read the MetaFilter thread: my mother-in-law served as a substitute bride.

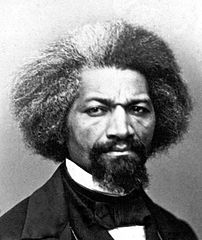

The photograph featured at the top of this post is of Mario Chavez embracing his wife Lizeth through the US-Mexico border fence at Playas de Tijuana. The original photograph is copyright David Maung, and was published by Human Rights Watch; a higher-resolution version is available at their website.

Just a reminder: here’s the next post in the series.

It is truly curious to me that the main reaction of the mainstream media was to label this as racist. The Indianapolis Star actually initially responded to criticism by removing the immigrant’s mustache and republishing an otherwise identical cartoon! Of all the the things wrong with this image, race is the last thing I would single out. The problem isn’t inherently its depiction of race relations; if anything, it’s hard to say without knowledge of the political context what the ethnicity of that immigrant might be. The problem is inherent to this image’s portrayal of how immigrants actually conduct themselves in society.

It is truly curious to me that the main reaction of the mainstream media was to label this as racist. The Indianapolis Star actually initially responded to criticism by removing the immigrant’s mustache and republishing an otherwise identical cartoon! Of all the the things wrong with this image, race is the last thing I would single out. The problem isn’t inherently its depiction of race relations; if anything, it’s hard to say without knowledge of the political context what the ethnicity of that immigrant might be. The problem is inherent to this image’s portrayal of how immigrants actually conduct themselves in society.

Acuerdo de San Nicolás de los Arroyos, a treaty between different governors signed in 1852 to convene a Constitutional Convention that drafted the constitution of 1853, source

Acuerdo de San Nicolás de los Arroyos, a treaty between different governors signed in 1852 to convene a Constitutional Convention that drafted the constitution of 1853, source