During the height of the cold war a common fear among the west and Soviet blocs about the other side placing nuclear weapons in outer space. This was why Sputnik mattered so much – Americans weren’t angry that Soviets had proven their intellectual superiority. Americans were scared that the Soviets might use their artificial satellites to attack them.

The immediate reaction to Sputnik was sparking the space race, an unofficial competition between the Soviet and western blocs to show their mastery over navigation in outer space. Publicly the space race culminated with the American moon landing in 1969. The initial fear about nuclear weapons in space however was dealt a few years prior in 1967 with the passage of the Outer Space Treaty between the world powers.

The Outer Space Treaty today forms the base of international law regarding space and the celestial bodies. It not only barred the installation of weapons or military bases in space, but also set up the parameters regarding property rights in space. Of interest to us, it effectively recognized the right to migrate to outer space.

Article 1 of the treaty reads that:

Outer space, including the moon and other celestial bodies, shall be free for exploration and use by all States without discrimination of any kind, on a basis of equality and in accordance with international law, and there shall be free access to all areas of celestial bodies.

A plain reading of the treaty’s text appeals to the notion that anyone may migrate to outer space, so long as they do so peacefully. There are a few other catches, such as the need for non-governmental entities to follow the laws of their respective earth-bound government.

Article 6 reads:

The activities of non-governmental entities in outer space, including the Moon and other celestial bodies, shall require authorization and continuing supervision by the appropriate State Party to the Treaty.

Outer space does not have open borders as such. In order to initially arrive in outer space one must follow the rules of a state and continue to follow the rules of said state to remain in space. This is similar to existing maritime law, where a ship’s flag designates under which rules it sails. Despite these limitations outer space does enjoy a lite version of open borders.

Hopeful space migrants must follow the rules of a state, but it does not matter which state’s rules are followed. Spaceships marked with a Mexican or Madagascar flag have as much right to explore space as ships marked with an EU or USA flag. I suspect that future space explorers will make frequent use of flags of convenience in order to gain access into space.

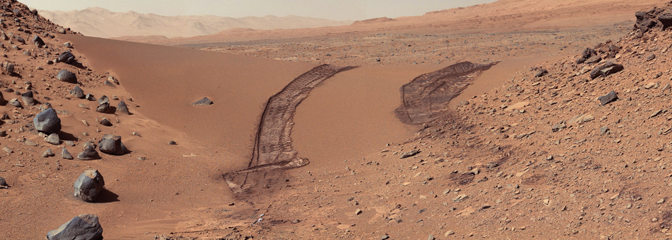

Am I suggesting that the open borders movement shift its focus to getting people to migrate to outer space? Not at all. Outer space has countless artificial satellites but no permanent colonies at present. For the foreseeable future this will remain the case. Even when a serious effort is made to colonize outer space I would not recommend migration there to the greater number of mankind as the journey itself would be expensive and have little reward.

Some significant catalyst must occur before it becomes efficient for large numbers of humans to settle space. Migration to the new world occurred when large economic opportunities awaited at the other side and/or when domestic forces pushed a population toward migration. The same general forces will be at play in deciding when space is colonized. Perhaps early colonization will be lead by Patri Friedman’s great-grandson in an attempt to promote space-steading. Who can say?

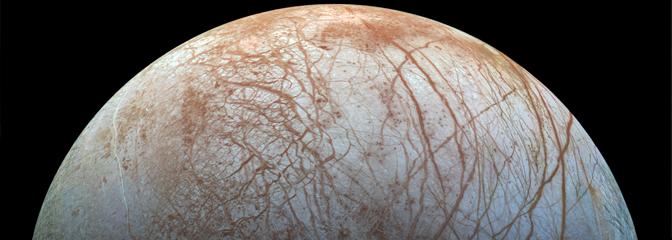

All the same there is some comfort in knowing that when these catalysts occur mankind will have the right to migrate to outer space. They will still have to find a means to do so, but at minimum they will not be pulled over at a border check point outside Mars and present their visas.

In the present the right to migrate to outer space presents us with a rhetorical weapon. If as I argue there is a right to migrate to outer space, why is there not a right to migrate to the new world? Outer space is described as the common heritage of mankind, but does this definition not also apply to the new world? Christopher Columbus first set sail in 1492, a little over five hundred years ago. This is a small amount of time in historical terms. When first discovered the new lands had a negligible existing population and today most of its inhabitants are descended from European, African, and Asian migrants. There is no meaningful ‘American’ race.

A Spaniard had no lesser right than an Englishman to settle the new world back then. Under what justification then do modern American countries erect barriers to entry? Did the new world cease to be a common heritage of mankind? If so, when and under what conditions? Under those conditions would it be proper for future Lunians, the descendants of human colonizers on the Moon, to set a quota on the number of migrants from Earth?

Further Reading

Will technology make borders obsolete? by Chris Hendrix

Argentina and Open Borders by John Lee

Full text of the Outer Space Treaty via the US Department of State.

Full text of the Moon Treaty via Wikisource.

The Moon Treaty was a proposed follow-up agreement to the above mentioned Outer Space Treaty. The Moon Treaty would have handed governmental control over the Moon, outer space, and celestial bodies to the United Nations. The Moon Treaty is widely considered defunct as it failed to acquire the agreement of those nations actually capable of space exploration.