Substandard working conditions recently murdered over 1,000 people in the deadliest garment factory accident in history. This accident in Bangladesh drew attention to the substandard wages of “sweatshop” workers in the developing world, and industrialists’ scant regard for their workers’ safety. Many on the left in the developed world saw this as an indictment of free market economics, urging government action to prevent such future disasters. Responding to such pressures, the US government recently raised tariffs on a number of Bangladeshi goods. I’m as concerned as anyone that Bangladeshi workers aren’t earning a fair wage or working in dangerous conditions. So it strikes me as strange that utterly absent from this debate has been the one measure that we know for sure would alleviate these conditions for countless Bangladeshis.

If we truly find it disgusting that Bangladeshis aren’t earning a fair wage for their work, or are being forced to work under slave-like conditions, we should ask ourselves: who is trapping Bangladeshis in their antiquated, inefficient economy? Do Bangladeshis really want to risk death every day to earn a pittance?

The standard analysis of this problem points out that the alternative to most Bangladeshis employed in industry is a life of subsistence agriculture. Farmers run the perennial risk of crop failure, and in the developing world, most subsistence farmers literally live hand to mouth, doing backbreaking labour in the sun. Industrial work may be risky, but it’s often a better alternative.

In response, you can argue that if people have to choose between a life of subsistence agriculture versus risking their lives for a job paying 50 cents an hour, this only illuminates the utter rottenness of the choices open to people in the developing world. And you’d be right. But it’s odd that we stop ourselves there. Sweatshops have been debated time and time again for decades, and yet hardly anyone seems to have stopped and asked themselves why these are the only two real choices open to sweatshop workers of the world. What’s keeping the Bangladeshi in the factory from doing the same work at a better wage elsewhere?

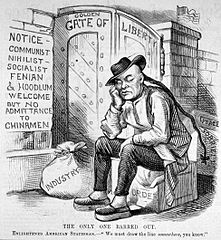

The answer, quite simply, is us. By politically and morally legitimising laws that ban Bangladeshis at gunpoint from working in our countries, we have left them no choice but to toil away in sweatshops. If we allowed them to cross borders in search of work, how many of them do you think would embrace the abominable wages and working conditions they’re forced to endure right now? Hundreds of thousands of Afghans literally risk being shot to death today so they can find work in Iran — if we allowed people to search for work across borders, without fear of abuse and murder, how much longer could sweatshops endure?

Part of the reason compensation in Bangladesh is lower than it is elsewhere is simply because of the differences in its economy versus the economies of developed countries: skill and human capital levels are different, the cost of living is different. But a major reason Bangladeshis are so underpaid is because we, the citizens of more developed countries, ban Bangladeshis from earning higher wages. The economic concept of the place premium illustrates this quite well: statistical analysis allows us to take an identical person and predict how their wages for doing the same work would vary depending on which country they work in.

When you consider the place premium, the magnitude by which people in the developed world are underpaid for their work is astonishing. People in the West get upset by wage discrimination on the basis of gender; without adjusting for statistical differences, women might underearn men by almost 30%. The magnitude of wage discrimination on the basis of nationality is so shocking, I cannot find any term to describe it that would be less apt than global apartheid.

For the exact same work that their American counterparts do, Bangladeshis are underpaid by almost 5 times — in other words, they are underpaid by almost 80%. And they aren’t even the worse victims of global apartheid — Yemenis and Nigerians are underpaid 15 times over compared to Americans. If Americans had allowed those dead Bangladeshi workers to work in the US, doing exactly the same work they were doing, not only would they be alive today, but they would be earning 5 times as much.

It is morally unconscionable that our conversations about sweatshops ignore the elephant in the room: we are the ones who put those sweatshop workers to death. It wasn’t just that we bought the goods those workers produced. It was that we banned those workers from working for us in our countries. We forced them to stay in Bangladesh, despite knowing that this would guarantee them an unfair wage and unsafe working conditions. We made them slaves to those sweatshops because they had no other choice — we took all their other choices away from them.

Until labour mobility and freedom of movement become part of the conversation about our economic rights and responsibilities, we might as well not be having any conversation at all. To ignore our immense fault for these people’s plight is morally callous and unjustifiable. In concluding his seminal 1997 essay on sweatshops, Paul Krugman wrote:

You may say that the wretched of the earth should not be forced to serve as hewers of wood, drawers of water, and sewers of sneakers for the affluent. But what is the alternative? Should they be helped with foreign aid? Maybe–although the historical record of regions like southern Italy suggests that such aid has a tendency to promote perpetual dependence. Anyway, there isn’t the slightest prospect of significant aid materializing. Should their own governments provide more social justice? Of course–but they won’t, or at least not because we tell them to. And as long as you have no realistic alternative to industrialization based on low wages, to oppose it means that you are willing to deny desperately poor people the best chance they have of progress for the sake of what amounts to an aesthetic standard–that is, the fact that you don’t like the idea of workers being paid a pittance to supply rich Westerners with fashion items.

In short, my correspondents are not entitled to their self-righteousness. They have not thought the matter through. And when the hopes of hundreds of millions are at stake, thinking things through is not just good intellectual practice. It is a moral duty.

That is a perfect summation of the case for doing business with sweatshops — except for one thing. Krugman utterly ignored the possibility of allowing the wretched of the earth to serve as sewers of sneakers for the affluent outside their home country. Allowing people to work under alternative economic and legal regimes if they are born into unjust and insensible regimes only makes sense. What reason do we have to not consider this alternative that Krugman couldn’t even bother to list? Are we willing to deny desperately poor people the best chance they have of progress for the sake of an aesthetic standard — because, say, we don’t like the idea of guest worker programmes?

Our conversation today on sweatshops automatically takes open borders off the table. We automatically rule out the one thing that would automatically abolish sweatshops, and automatically give the people of the world a fair choice in determining where they work and on what terms. What reason do we have not to give this proposal serious consideration? It’s our guns and tanks that ban good, honest people from taking better-paying jobs — that ban people from working in safe factories where they won’t have to worry daily about the roof caving in or the machinery catching fire. We need a damn good reason not to consider revoking our ban on people seeking fair work at fair wages.

In our conversations today, I just don’t see those reasons. And so as Krugman says, I don’t see how anyone in this debate can be entitled to their self-righteousness. Anyone ignoring labour mobility, or the fault of the developed world in banning poor people from looking farther for work, has simply not thought matters through. They have not done their moral duty. If you won’t consider open borders as a solution to sweatshops, then don’t bother complaining about sweatshops at all. You’re clearly not interested in solving the problem.