This kind of political reasoning is sometimes labeled Burkean conservatism. Edmund Burke, an Irishman who migrated to England, is often regarded as the founder of modern Western conservatism. Contrary to what the conservative label may suggest, he was no opponent of change; in criticising the French Revolution, he wrote: “A state without the means of some change is without the means of its conservation.” Burke merely preferred a bias in the political process against change: you shouldn’t change things without a really really good reason. I don’t think of myself as a political conservative, but this seems like a fairly reasonable principle.

So before we tear down the walls our governments have erected, we should ask why these walls went up in the first place. This is not a question that is new to us, mind you; we first discussed it on this blog two years ago. The answer to Chesterton’s question depends, of course, on which country you’re a citizen of.

So, where did the idea of border controls and deportations for our colonial masters come from? Well, in the case of Malaysia’s former colonial power, the United Kingdom, the first notable instance of the mass deportation and collective punishment of migrants was when King Edward I expelled all Jews from England. A few were allowed to return for visits on temporary visas, but between 1290 and 1657, all Jews residing in England were actually illegal immigrants. So at least in the case of the UK, border controls were originally rooted in racial and religious bigotry, not any sound policy reason.

Let us return to my country’s former colonial master, the British. While the first recorded large-scale deportations occurred in 1290, the first recorded immigration legislation was actually the Aliens Act 1793. Prior to 1793, there actually were no legally-required controls or restrictions on foreigners entering the UK. This law imposed a new requirement on foreigners entering Great Britain: they must register their arrival with the government upon entry, and with a local Justice of the Peace. Failure to register would result in jail, pending deportation.

What was the reason for this law? The UK government archives today say: “It was introduced to manage the influx of people coming to Britain to escape the French Revolution.” But in reality, it was enacted to exclude French republicans who might have made their way to Britain, mingling among refugees. Fervent opponent of the French Revolution that he was, Edmund Burke favoured this law.

Curiously, Burke supported the Aliens Act 1793 even though it stripped foreigners of the right to habeas corpus: the right to challenge your detention in court, an ancient legal tradition rooted in the principle that no government may lock someone up and take away their liberty without just cause.

Under the Aliens Act 1793, the punishment for failing to register was not a fine. You could be jailed without bail and deported, without any right of habeas corpus or appeal, simply for failing to register. You could even be a bona fide refugee, with no revolutionary connections, and it would not matter one whit: you had no recourse to challenge your detention or deportation. The law’s own sponsor called it: “a bill for suspending the Habeas Corpus Act, as far as it should relate to the persons of foreigners.”

Did Burke ask himself whether he was unthinkingly tearing down Chesterton’s fence? Probably not; this was decades before Chesterton would be born. But one wonders what Burke was thinking. In 1789, Burke wrote: “Whenever a separation is made between liberty and justice, neither, in my opinion, is safe.” If anything counts as an injustice, surely it must be arbitrarily taking away the basic liberties of an entire class of people — not on the basis of any wrongdoing, but simply because of their condition of birth.

Oh, but it’s just foreigners being deprived of their liberty, you might say. Except that the Aliens Act 1793 was just the precursor to the Habeas Corpus Suspension Act 1794 — which is exactly what it says on the tin. Now nobody in Britain, citizen or foreigner, enjoyed the safeguards of the ancient writ of habeas corpus.

It is of course easy to condemn Burke and his Parliamentary colleagues in retrospect. If we had been in their shoes, facing possible insurrection fomented by, or invasion from, Revolutionary France, we too may have passed the same suspension of habeas corpus.

But this incident illustrates an important principle that guides how I think about immigration law: if a circumstance so endangers our state or society that we must restrict basic freedoms, then so be it. But if such a circumstance is only dangerous enough to warrant invading the rights of the peaceful stranger in our land — whilst leaving potential traitors, terrorists, or criminals amongst our own citizenry unaffected — then I am much more skeptical. Either the situation is so dire that everyone’s liberty must be put at risk, or it is simply not that dire.

Of course, there are fine gradations in between “that dire” and “not that dire”. And the more dire the situation is, the more justified and less arbitrary some distinctions based on nationality or even ethnicity become: how strongly would one object to Polish controls on German entry in the days leading up to the Nazi invasion of 1939? The problem of justice arises when you assume every scenario our governments face is tantamount to that kind of emergency. At some point, you land on a slippery slope that has you deporting Jewish refugees and throwing your own citizens into prison camps.

And while situations like a literal world war may merit restrictions on the movement of foreigners, no sane person can claim we live in such a situation today. When we aren’t at war, and when most of the people seeking entry to our shores are citizens of countries at peace or even allied with us, you can’t simply erect an automatic bar to entry on the basis that governments need extraordinary power to protect us from an invasion that nobody believes is coming.

In spite of this, discretionary and arbitrary immigration controls which assume every immigrant poses a dire threat to our society, guilty until proven innocent, are the laws of almost every land today. I submit that such paranoid discriminatory laws are all out of proportion to the risk immigrants pose. Of course anyone can name an immigrant who has done something wrong. You can select any sufficiently large group of people and find all kinds of criminals and wrongdoers amongst them. But the burden of proof rests on the restrictionist to show that arbitrarily excluding most foreigners is in fact a sound and proportionate policy.

This is quite Burkean, really: mind you, the alien registration requirement which Burke supported was later repealed after the crisis had passed. A literal Burkean immigration policy would be open borders, with the temporary suspension of habeas corpus in times when invasion or insurrection seemed imminent. The UK’s first immigration controls were only enacted over a century later with the Aliens Act 1905.

The roots of this law? Well, it came after the passage of anti-Chinese immigration laws in colonies like Canada and Australia. It explicitly borrowed wording and diction from the United States’s own anti-Chinese immigration statutes. Like Edward I’s Edict of Expulsion in 1290, its primary target was immigrant Jews.

Although on this occasion, the government had enough scruples to avoid any explicit reference to race, as historian Alison Bashford and law professor Jane McAdam document, contemporaries understood the law’s definition of migrant to be aimed at Jews originating from eastern Europe, and the law was incessantly criticised for its anti-Semitism. More than that, opponents explicitly attacked the law for uprooting ancient British tradition (emphasis added):

For many British parliamentarians, then, the introduction of the Aliens Act was not merely a natural response to a world of increasing global movement (and regulation of that movement); it was a highly controversial step. It was considered ‘drastic’ and ‘revolutionary in its character,’ even by those who put forward the various bills. Many considered that the principle of free movement, and, accordingly,the tradition of having no entry regulations, was part of what distinguished British practice; even part of what constituted British “liberty.”

The response of its advocates, such as Herbert Asquith, who would later serve as British Prime Minister? To embrace these accusations. Bashford and McAdam (emphasis added):

Asquith spoke in support of the bill, but nonetheless recognized its significance: “This Bill, it must be conceded, is an entirely new departure in legislation, for it gives to an officer of the Executive, by his own act, without any reference to a Court of law or to judicial procedure, power to prohibit admission to these shores of any person who is not a subject of the Crown, provided he comes within certain categories.”

The suspension of habeas corpus, limited to times of great danger in Burke’s day, now became an everyday occurrence for any foreigner daring to enter Britain. The revolutionary and radical arbitrary dictatorial power of the government to exclude foreigners at will was now enshrined. Today, it has been so commonplace for the past century to the point that we hardly think of it.

So if we think of immigration restrictions as Chesterton’s fence then, how should we characterise the rationale for erecting this fence? If we look at the raw texts of these statutes, we find many references to excluding paupers, the diseased, and the criminal. We can debate the extent to which these exclusions are just, but many of them make some sense on the face of it. But if we look at the intentions of the men (and women, to the extent they were involved) who drew up and bequeathed to us the founding principles of modern immigration restrictions, we find some of the worst and most blatant injustices in the history of mankind.

Immigration laws were established in theory to promote public safety and order. But in reality, their promoters drew them up to exclude people solely because of the colour of their skin, or the religion they practiced. You merely have to scratch the surface of these laws to uncover some of the ugliest expressions of base bigotry and prejudice, be it against the Chinese, the Japanese, the Italians, the Irish, the Jews, and so on. Little wonder that journalist Stephan Faris in his review of the modern border regime could write of things coming full circle, with South African apartheid using “immigration laws” as a figleaf to disguise blatant racism:

To be sure, there are differences between the global system of immigration restrictions and South Africa’s attempt to entrench white privilege through the partitioning of its territory. But it should give us pause to think that when the architects of one of history’s most recognized evils set out to codify their system of injustice, they looked at our borders and passports and saw a lot to like. Intentions aside, the biggest difference between the two is that the South Africans wanted to draw the boundaries and assign the nationalities. We make do with the existing ones.

It may of course be true that serendipitously, these laws founded in racism and unempirical prejudice are in fact beneficial and good. But let’s have an open conversation about the benefits of these restrictions then. Let’s place the burden of proof where it belongs: on those who want to prop up those legal walls and fences erected to preserve and entrench bigotry.

Once we have established the original rationale for these laws and found them wanting, we can no longer resort to tradition as reason enough to keep them. Whatever your views on the issues of gay marriage and family rights, I think US judge Richard Posner’s pointed questions in the litigation of this issue apply all the more to border controls:

Posner: What concrete factual arguments do you have against homosexual marriage?

Samuelson: Well, we have, uh, the Burkean argument, that it’s reasonable and rational to proceed slowly.

Posner: That’s the tradition argument. It’s feeble! Look, they could have trotted out Edmund Burke in the Loving case. What’s the difference? . . . There was a tradition of not allowing black and whites, and, actually, other interracial couples from marrying. It was a tradition. It got swept aside. Why is this tradition better?

Samuelson: The tradition is based on experience. And it’s the tradition of western culture.

Posner: What experience! It’s based on hate, isn’t it?

Samuelson: No, not at all, your honor.

Posner: You don’t think there’s a history of rather savage discrimination against homosexuals?

The only distinction here is that border controls aren’t even a real tradition. The kind of controls on the scale first adopted in the late 19th century and early 20th century didn’t exist in Burke’s day. Massive border controls that arbitrarily restrict human movement purely on the basis of a condition of birth are a modern innovation. And, to borrow Judge Posner’s words, they are an innovation rooted in hate and savage discrimination.

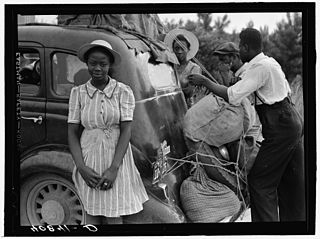

Arizona farmers protest Japanese and Indian farming in the state, 1934. Source: Americana, the E-Journal of American Studies in Hungary.

Immigration controls are an injustice that we must tear down as far as we can. “This policy benefits our race” or “this policy benefits our country” are not reasons enough to excuse a preventable injustice. As Burke himself said:

Justice is itself the great standing policy of civil society; and any eminent departure from it, under any circumstances, lies under the suspicion of being no policy at all.

In 1879, Chinese-Australians Lowe Kong Meng, Cheok Hong Cheong, and Louis Ah Mouy authored a pamphlet lamenting the racist immigration laws that uprooted their freedom of movement and residence. Today, in this era of vast migration restrictions, their words ring true literally more than ever before:

In the name of heaven, we ask, where is your justice? Where your religion? Where your morality? Where your sense of right and wrong? Where your enlightenment? Where your love of liberty?

We recognise today the great wrongs that our border controls once visited upon the Chinese, Jewish, or other migrants of the day. But we preserve the same principles of dictatorial discretion and arbitrary discrimination that marked the very exclusionary and unjust laws which victimised these people. There may be good reasons to preserve border controls. But unless you unreservedly embrace prejudice as a sound principle for making policy, Chesterton’s fence is not such a justification. Rather than sound and solid policy, the foundations of our border controls are just rotten cesspools of hatred and bigotry.

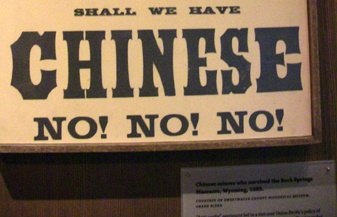

The image featured at the top of this post is of an exhibit from the Museum of Chinese in America, depicting a poster from the late 19th century advocating the exclusion of Chinese immigrants. The photograph of the exhibit is from Robin Lung.