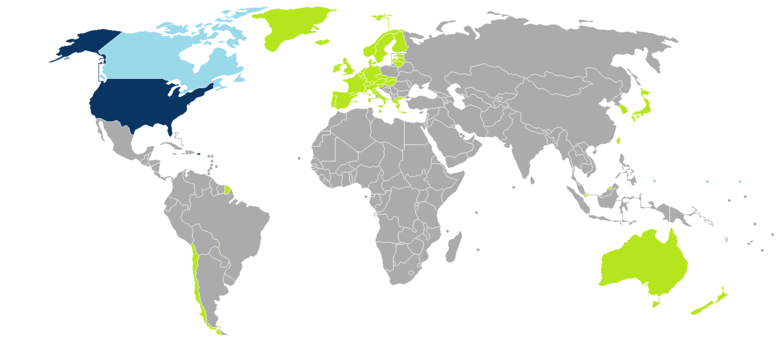

Credit for featured image: Wikimedia Commons. It shows in green the countries eligible for the US Visa Waiver Program. For more, see the Wikipedia article.

A few years ago, the South Carolina Journal of International Law and Business published an article by then-law and business student Robert Wilson on the risks that US visa policy poses to trans-Atlantic foreign relations. The article is a good and I think fair review of the case for and against stricter non-immigrant visa policy. Wilson never hides that he favours a looser policy, but he accurately notes the reasons why the US government has felt compelled to tighten the borders.

Wilson’s focus is on the US visa waiver programme (VWP) which allows people from certain countries to enter the US without a visa. They simply need to pass a quick (30 seconds is the figure he cites) check at border control. Wilson notes that this is how some of the 9/11 terrorists were able to enter the US. This is why since 9/11 the US has mandated interviews for almost all visa applicants, and why the US has been reluctant to extend the reach of the VWP.

Visa Waiver Program I-94W form that any person from a VWP-eligible country needs to fill in when landing in the US for a short-term, VWP-eligible trip. Source: magazineUSA.com

But as Wilson notes, sealing the borders in this manner is not practical. It is not any more useful or pragmatic than demanding the search of every cargo container entering the US for bombs or drugs. Other than a cursory check at the border, the VWP essentially throws open US borders to eligible foreigners, with no obligation to present additional information prior to entry. And these foreigners are screened not on any meaningful factual basis other than national origin: an person from Nigeria has to face stringent checks prior to boarding a flight to the US, while an identical twin who happens to have British citizenship can waltz right on up to the border.

I am in favour of open borders, but this manner of implementing them strikes me as arbitrary and self-defeating. Just as there are safe ways to deregulate, there are also plenty of unsafe ways, and this arbitrary discrimination strikes me as just one such unsafe way. Wilson cites how the number of people travelling to the US for tourism and business has been falling since 9/11 because of stricter visa procedures, while equivalent figures for other countries have been trending up.

Wilson recommends the US pre-screen VWP-eligible foreigners, using a system similar to Australia’s. Nathan Sales, a law professor, testified before Congress that this approach would be much more sensible compared to the arbitrary status quo, and more importantly, would allow the US to expand the reach of the VWP. It makes sense to me: a government can legitimately limit entry at its borders if it justifiably believes that this addresses a concerning security risk. Refusing to submit basic biographical information or fill out a basic form signals that you are likely to be a risk of some kind.

I’ve used the Australian electronic equivalent of the VWP before: it’s straightforward and transparent. It’s not open borders, but I’d much rather have an extended visa waiver programme on a similar basis, open to as many people as possible. My belief is that the government should approve visas for anyone who is acting in good faith. Right now, the US denies visas to over 1 million people annually for essentially no reason (they’re not criminals, not carrying communicable diseases, etc.). Give those 1 million people the visas they need to visit or study.

One final point Wilson raises is that expanding the VWP to all the European countries who desire it would allow cooperation with those countries in immigration enforcement. By coordinating governance systems in this area, the US could more effectively deter people with outstanding criminal issues from entering, while opening the borders to those acting in good faith. If the US pursues this, this could eventually lead to trans-Atlantic open borders: even if border controls remain, visas would be available to all good-faith visitors, and one day perhaps even workers or immigrants.