Tyler Cowen recently linked to a piece by Eric Rasmusen about potential scenarios where immigration hurts the American economy.

Rasmusen considers a few variations on the Cobb-Douglas production function where the amount produced by the economy is given by the equation: $latex Q=L^{.7}K^{.3}$ where L is the total amount of labor and K is the amount of capital available for production.

According to this model, if L = 100 and K = 100, the total production is 100. Of this amount, 70 is divided among the laborers and 30 goes to owners of capital. If L increases to 140 due to immigration and K remains constant, total production increases to 126.6. 38 of this goes to capital, 63.3 goes to native labor and 25.3 goes to immigrant labor. So capital wins and native labor loses. The amount capital gains is a bit more than the amount native labor loses.

This is a pretty standard analysis, but we should note that it assumes that K remains constant. This is the sophisticated equivalent of assuming that the number of jobs is constant, so that when immigrants enter the country they take “our” jobs. In fact, the amount of capital devoted to production depends on demand, which depends on the number of consumers. Since immigrants are consumers in addition to laboersr, we can expect the amount of capital devoted to production to increase.

But this isn’t the biggest complaint I have with the paper. In his analysis of the standard Cobb-Douglas approach, Rasumsen makes some very confusing comments about the impact of taking the welfare of immigrants into consideration:

“What about the benefit to immigrants? Some readers will want to include those in the policy objective for the United States… Although American labor definitely loses, immigrant labor either wins or is unaffected. The aggregate benefit to labor can be negative because if foreign wages are just a little bit lower than American post-immigration wages, then the gain to the immigrant labor is very small, while the loss to American labor is unaffected and therefore exceeds the immigrant gain. In fact, one might expect that if there is open immigration and the amount of immigration is 40, it must be that wages in the other country are .63, i.e., immigration stops at 40 because foreign and American wages equalize. Suppose further that the rest of the world is large compared to America, so that the rise in wages elsewhere in the world as a result of emigration to America is trivial. Then, the immigrants have neither gained nor lost by immigrating to America. The only welfare effects are the loss to American workers and the gain to American capital-owners.”

This analysis is baffling. If we are using the Cobb-Douglas model to understand the impact of immigration on the US, let’s use the same model to understand the global impact. In particular, let’s assume that we have two countries. In the US, L=100 and K=100, so Q=100 just like in Rasmusen’s model. But then let’s assume that there is one other country where labor and capital are out of balance. That is, L = 1000 and K=50 with the result that Q=407.1. Total production between the two countries is 507.1. Now what happens if we open the borders between the two countries? Then we can combine L and K so that L=1100 and K=150. But we don’t simply add the Q’s. In fact, total production is now 605.1. We got an additional 98 production for free!

How did that happen? We even assumed that the US contribution to K didn’t go up in response to the open borders, a likely result that would push the numbers up even more (if K went all the way up too 1100, then production would go up to 1100 as well). The reason is that the best way to maximize output under the Cobb-Douglas model is to evenly distribute the capital among laborers, not to split it up in disproportionate pieces.

Of course, it remains true that if we prevent K from going up then native labor will suffer. In the closed borders regime, the 100 native laborers received a wage of .7 each and the 1000 foreign laborers got .284. Under the open borders regime, all laborers got a wage of .38. Again, this is because we assumed that K remained constant.

Rasmusen includes a few other scenarios in which not only does native labor lose, but net American output per person goes down. The most plausible of these is a scenario in which he assumes that the production function is a modified Cobb-Douglas function $latex Q=(L^{.7}K^{.3})^{.8}$, which represents the idea that we have diminishing returns to the combination of labor and capital. This could be due to a fixed amount of natural resources or land. In the basic model, the amount capital gains is more than the amount native labor loses. With this modified model, the amount capital gains from immigration is less than the amount lost by native labor.

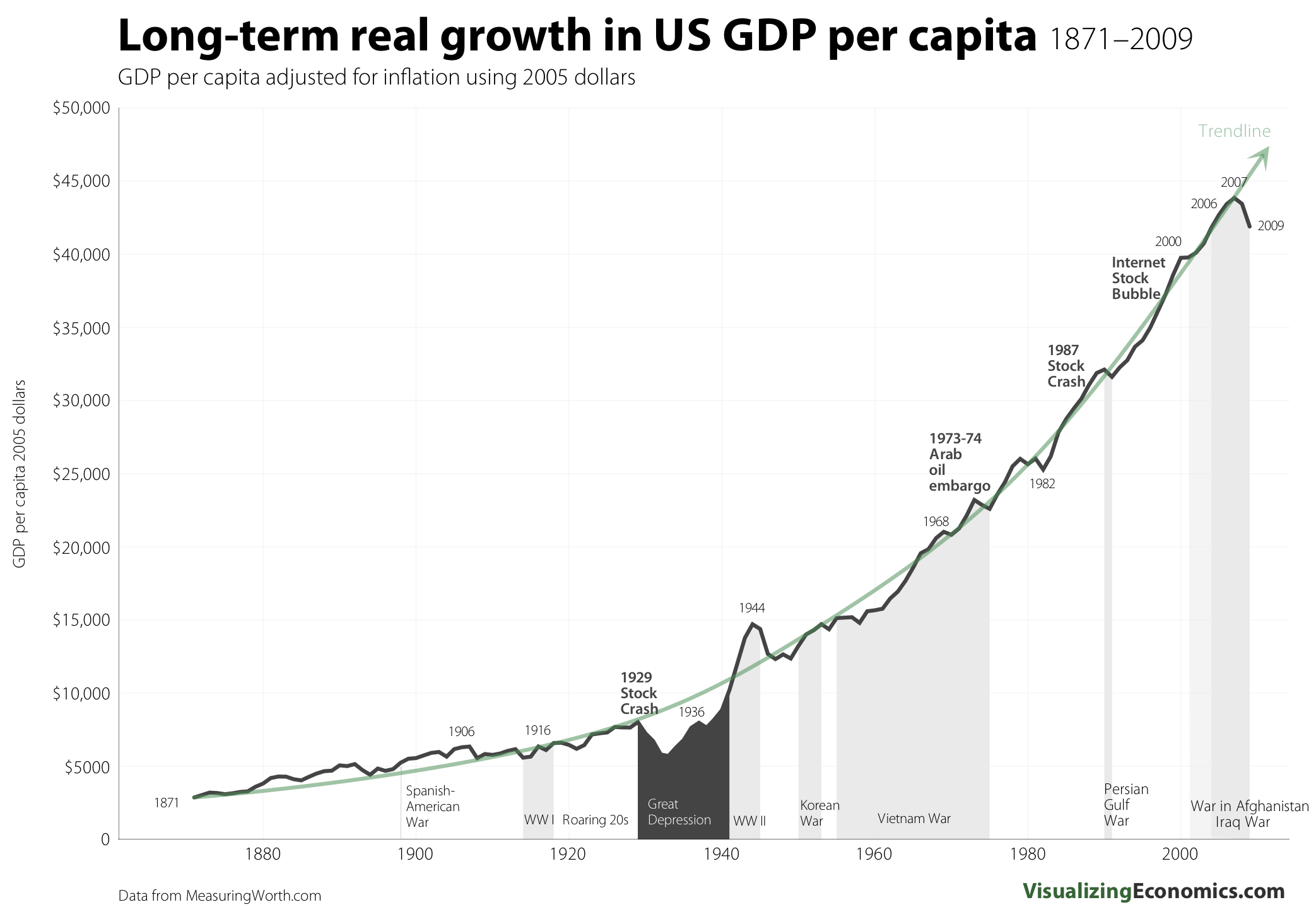

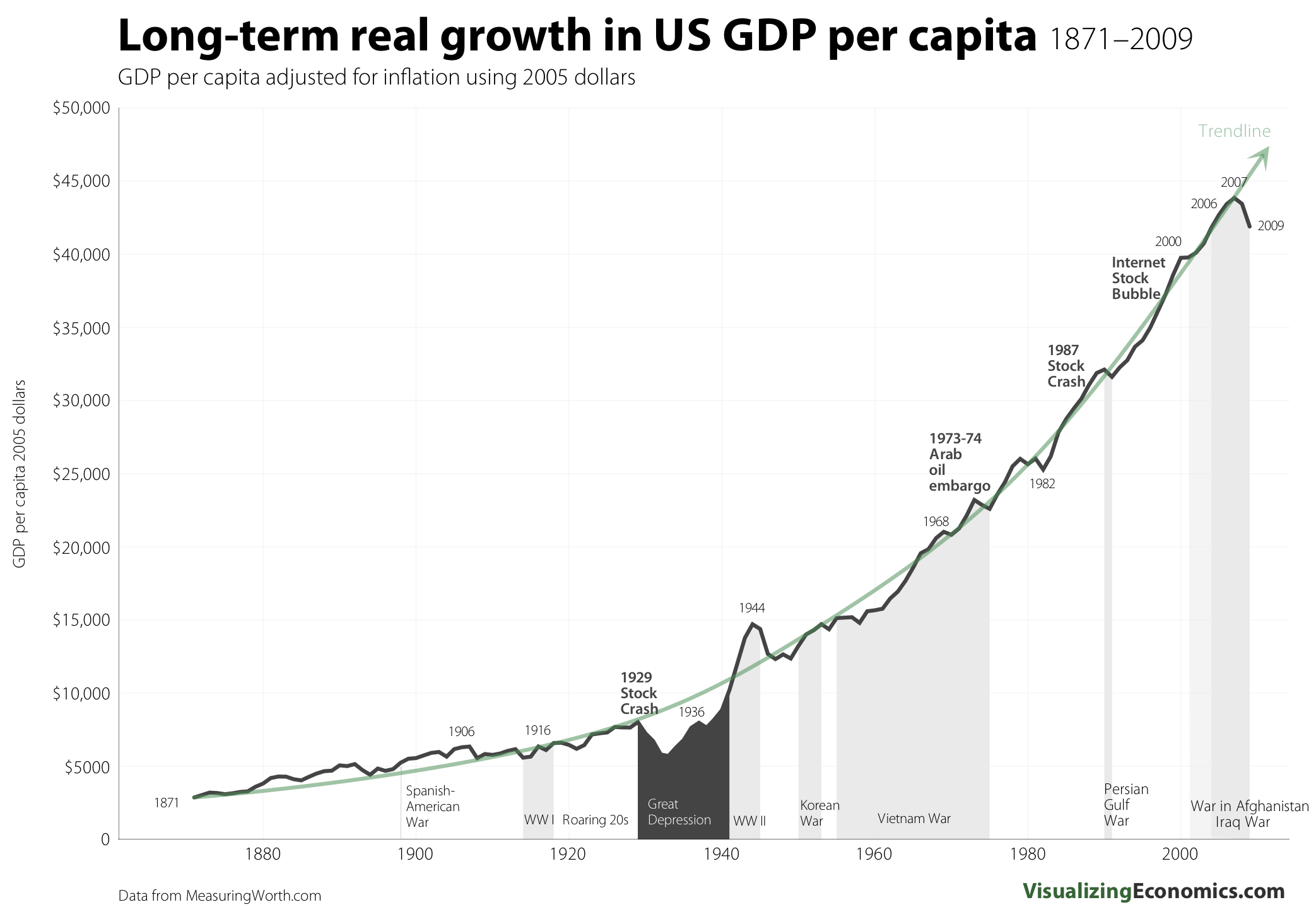

The problem with this model is that it seems to run counter to experience. It would imply that as our population grows, there would be a very strong tendency for GDP per capita to decrease. That is, the result is not specific to immigration. It applies to any form of population increase. Our population has been growing steadily the nation was founded. Here is a graphic showing the results for GDP per capita:

Of course, Rasmusen doesn’t argue that any of his models actually represents reality. He is trying to explore scenarios in which immigration creates a net economic detriment to natives. In the basic model, cash transfers from capital to labor (e.g., progressive taxation) can be used to compensate native labor. In the modified scenario, the net loss to natives prevents such a program from working. Luckily, the model doesn’t seem very realistic, at least based on our historical experience.