Goldwater is a name synonymous with the rebirth of American conservative, right-wing politics. But it is also a name that should be synonymous with open borders. In 1962, Barry Goldwater jotted down some thoughts on where his beloved Arizona would be in 50 years. On immigration and Mexico, he said:

Our ties with Mexico will be much more firmly established in 2012 because, sometime within the next 50 years, the Mexican border will become as the Canadian border, a free one, with the formalities and red tape of ingress and egress cut to a minimum so that the residents of both countries can travel back and forth across the line as if it were not there.

To a certain degree, his vision came true ahead of time. Stories of lively cross-border interactions pre-9/11 abound. After the post-9/11 crackdown on border movement, it became much harder to cross the Mexican border with the US without enduring much lengthier delays than existed before. Goldwater’s vision plainly does not exist today.

Of course, to some degree, one can argue that Goldwater wasn’t really arguing for true open borders (though I find it interesting that Goldwater pointedly refers to the “residents of both countries,” as opposed to just citizens). Canadians themselves face a fair number of immigration restrictions in the US. The popular television show How I Met Your Mother has made fun of this by depicting a Canadian character’s issues with her work visa forcing her to consider a sham marriage with a friend. This theme is fairly popular in the media, actually; Ryan Reynolds and Sandra Bullock starred in The Proposal, a film based on a very similar storyline, also about a Canadian woman forced into a sham marriage to hold down her job in the US.

These pop media depictions have a basis in reality. My current employer used to hire non-US residents frequently. It stopped doing this a few years ago not just because of the cost, but because of the immense uncertainty about whether a work visa would actually come through. It’s no use hiring someone only to have to bid goodbye to your tens of thousands of investment in that person’s training thanks to immigration enforcement. Canadians at my firm were no exception to this; I met someone who transferred to my office from our Toronto office very shortly before we stopped sponsoring work visas; he told me he actually decided to work for us in Toronto because he wanted to work in the US in the first place.

So no open borders for Canadians. But looking at Goldwater’s statement, I don’t think he would have expected the kinds of restrictions my Canadian colleagues put up with. One can hardly describe a convoluted work visa process as an immigration law that cuts the formalities of ingress and egress to a minimum. One can hardly say that Canadians can cross the US border as if it were not there! Maybe Goldwater was only imagining open borders for tourists, but that doesn’t sound like the sort of thing someone dreaming about the next 50 years of progress would be focused on.

Modern US conservatives would do well to hark back to Goldwater (and Ronald Reagan, for that matter, considering his willingness to embrace “amnesty”). The nature of North American trade and physical borders means closed North American borders are legislating against economic and geographic reality. Instead of trying to build an expensive and unrealistic wall, the sensible thing to do is to allow those acting in good faith to come and go — and monitor these legal movements carefully to filter out those with ill intent. In fact, this is a lesson from another famous US conservative’s Operation Wetback. Reflecting on Dwight Eisenhower’s policy, Alex Nowrasteh writes:

By the early 1950s many unauthorized migrants were entering alongside Braceros to work, mainly in Texas. The government responded with the now infamous Operation Wetback that removed almost 2 million unauthorized Mexicans in 1953 and 1954. Unlike today’s removals and deportations, the migrants were only required to step over the border into Mexico and could then step back in and lawfully sign up for the Bracero program. As a result, the number of removals in 1955 was barely 3 percent of the previous year’s numbers and those who previously would have entered unlawfully instead signed up to become Braceros, which was the intended purpose of Operate Wetback. The government did not tolerate unlawful entry but made it very easy for migrants to get a guest worker visa and used Border Patrol to funnel unauthorized migrants and potential unauthorized migrants into the legal system.

US immigration policy consciously makes it difficult for Canadian white-collar professionals to work in the US, and essentially impossible for Mexican blue-collar professionals to work. Is it any surprise that the white-collar professionals of the world would rather go elsewhere, while the blue-collar professionals sneak in to work?

Restrictionists and those critical of open borders contend that Operation Wetback “succeeded” in the sense that it deported millions of people, and most of them did not come back. Calls for Operation Wetback II or variants of it are not uncommon; they appear on FOX News and on stage at presidential debates. But US law then, unlike now, was not prejudiced against previous deportation victims. You could still re-enter as a Bracero legally right after you were deported; the whole point of deportation was to encourage you to re-enter legally, not to erect further barriers to your entry. After all, if you were able to get in unlawfully before, you could certainly try again!

Conservatives need to recognise physical and economic realities, and use the legal system to work within them, instead of trying to pretend there’s some perfect form of “border security” that doesn’t involve doing battle with the fundamental realities of the North American map. Modern border enforcement proposals take for granted that it’s possible to control in totalitarian fashion large swathes of border territory. That may be so, but only if the state assumes a totalitarian form itself. As the American Civil Liberties Union would put it, to enforce the border, you’d need to erect a Constitution-free zone.

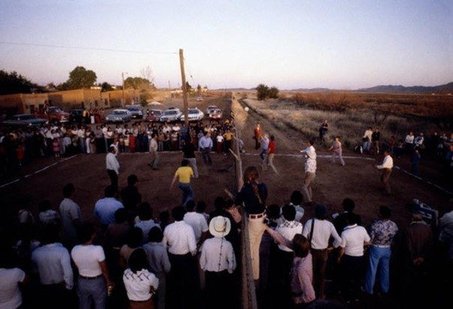

The photograph featured in the header of this post is of Americans and Mexicans playing volleyball over the border, circa 1979. Via RealClear.