A common retort to suggestions that our governments regularise the status of irregular immigrants is that these people are “criminals”, they’re “illegal”, and just what part of illegal don’t I understand? The mainstream immigration reform has adopted this rhetoric too, even if they claim to reject it; the rhetoric of US President Obama (who at the time I write just announced a deferral of deportation for some few million migrants) and others has been chock full of insistence that irregular immigrants owe a debt to society, that they ought to do some sort of penance — perhaps pay a fine — in return for any sort of regularisation. In short, the mainstreamers say that they do understand that these migrants are “illegal”, and that they do intend to punish them — just not as badly as the hardcore restrictionists want.

I see no justice in this. As co-blogger Joel Newman says, our governments owe irregular migrants an apology, not a fine. Make no mistake about it: if you’ve done something wrong, if you’ve injured someone or taken someone’s property, you ought to pay the price. But if all you’ve done is an honest day’s work, if all you’ve lived in is a home you’ve paid the price for, then there is nothing to punish you for. Living in the shadows our government forced you into for dreaming of a better future for yourself and a family was more than punishment enough.

The persistent, shrill cries of “what part of illegal don’t you understand?” are pretty blind to the meaning of the term “illegal” in the first place. For instance, most of these people don’t seem aware that it’s not a crime to be present without a lawful immigration status in the US; this is such basic legal knowledge that it didn’t make any headlines when the Supreme Court acknowledged this in an aside as part of a larger ruling on immigration law. For another, most of these people routinely break the law and get indignant when it is actually enforced against them. Just witness the furore when bicyclists are ticketed for cycling on the sidewalk, or when drivers are caught speeding by automated cameras. If committing unlawful acts in the course of ordinary business makes immigrants “illegal”, that makes everyone “illegal”.

Now of course people will say immigration law is on a special plane of existence, something that deserves far more respect than menial traffic laws. Sure. I simply say: let the punishment fit the crime.

The consensus is that half of all undocumented migrants in the US entered lawfully at a border checkpoint, and simply took up residence or employment in violation of the terms of their visa. There is no crime in paying rent for a residence, and no crime in searching for work. If an immigrant applying for my job is stealing from me, then who did I steal from when I applied for the job I hold now? Is it only a crime when immigrants do it?

These undocumented migrants should be punished appropriately for any actual crimes they have committed. If they drove drunk, if they shoplifted, if they committed welfare fraud, whatever — they should do the time, and pay the fine. But they should not be deported or excluded from the country they call home. As long as they are willing to accept the laws of their new home, and accept the punishments of these laws, they should be allowed to stay. They entered legally. The most they should be required to do to stay is fill out a basic form, and submit to legal proceedings for any other unpunished crimes in their past. Innocent immigrants who have done nothing worse than pay rent and earn honest wages deserve an apology for the persecution that our laws unjustly put them through.

As for the other half who entered without inspection at a border checkpoint, they should submit to a screening comparable to what they would have gone through at the border, and register with the authorities. Again, the idea is to make restitution for the original offense. The original offense, in legal parlance, was “entering without inspection”. So let the punishment fit the crime.

But it wouldn’t be fair, you might say. What about all the immigrants waiting in line? Well, whose fault is it that they are waiting in that line? Isn’t it your fault that the government you elected made crappy laws which have kept out all these innocent immigrants, and forced them to choose between waiting in a line that will never end (literally: some visa categories have backlogs that exceed 80 years), or migrating illegally?

I do agree it is not fair to do amnesties in a one-off manner. It is not fair to the good people who want to immigrate legally, but who are banned from doing so by irrational quotas and queues. It is also not fair to all of us who are harmed by the bad apples, the actual criminals, who either hide amongst the innocents in the undocumented population, or worse, take advantage of these migrants’ warranted fear of the government to abuse and exploit them.

Many governments — such as those of France and Germany, to name a couple you may have heard of — do not do one-off amnesties; instead, anyone who migrated illegally but who has otherwise complied with the law for a sufficient length of time is allowed to register with the government and become a legal immigrant. If we can’t have open borders, let’s at least allow anyone who has proven their commitment and loyalty to our laws to come out into the open and register as a law-abiding member of our community. That’s the fair thing to do, instead of having these one-offs.

But at the end of the day, if being fair to those immigrants in line is what bothers you so much, well — it’s the line your government created. The absurdity of having queues backlogged such that people applying today would have to wait an entire human lifetime to get their application approved is something only a government could create. The problem isn’t those good people forced to choose between waiting in line versus entering by other means to rejoin their families or seek gainful employment. The problem is your government and the stupid laws it made up.

Now, those laws aren’t stupid you might say. I agree: to the extent that they protect us from criminals, contagious disease outbreaks, and other harms, they are good laws. But to the extent that they “protect” us from people who just want to pay the market price to live in a safe home and work in a functioning economy, they are bad laws. To the extent that they treat someone whose ambition is to earn minimum wage washing dishes 18 hours a day as if he’s the scum of the earth, they are evil laws.

I’ve written before that the best way to secure the US’s border with Mexico would be to open it. Drug lords and slave traffickers rely on being able to disguise themselves among the masses of innocent people crawling through sewers to rejoin their families; let those innocent people buy bus tickets instead of paying thousands to coyotes, and where will the criminals hide? Restrictionists scoff at the idea of these immigrants being innocent — but you tell me, where’s the sense in treating someone who just wants to mop your floors for minimum wage as if he is the equivalent of a murderous drug trafficker?

I understand the intuition that one should comply with the law, and that failing to comply with the law generally marks you as a bad person — somewhere on the scale between reckless and just plain criminal. But this intuition only works for laws where the burden of compliance applies equally to everyone. Everyone knows what it means to not steal. But does everyone know what it means to comply with immigration law?

I would bet anyone that the majority of citizens of any country have no idea how the typical migrant in their country should comply with their own country’s immigration laws. Why should any of us know? All we ever did to comply with the law was be born. We didn’t have to do anything else, just slide out of the right person’s uterus at the right time, on the right soil.

Anyone in the US who has ever been in trouble with their taxes should know the feeling: you did everything right, and yet apparently your filing was still illegal — the government says you didn’t pay enough taxes. US tax law is so complicated that in some cases even the Internal Revenue Service throws up its hands and admits it doesn’t know what the law says. Yet for all your trouble, the public lambasts you as a tax evader, blasts you for not paying your fair share. And that is pretty rich, when virtually everyone who files taxes has likely fallen afoul of some technicality in the law (did you really report on your tax return the $20 in income you earned from that casual bar bet with your cousin?).

Multiply this frustration a few hundred times over and you can imagine the frustration of complying with immigration law. Some of the best, most honest and decent people I have personally known have been “illegal”. In some cases they didn’t even realise it until after the fact: as a student, your visa bans you from working more than a certain number of hours. Exceed the limit, and bam, you’re “illegal”. In other cases, delays or government processing issues while you’re transitioning from one visa type to another mean that you can “fall out of status” until your new visa is approved. Bam! Illegal.

And these are the lucky ones: they were already present in the US, and nobody could conveniently detect they’d committed these violations of immigration law. Usually nobody would ever be the wiser that they had, for a period of time, been “illegal”. Millions more such innocent people are trapped in the unlucky position of either waiting decades in line, or just jumping a fence that shouldn’t be keeping them out in the first place. Long wait times for immigrants to the US aren’t unusual; they’re the norm. Stories of the insanity of immigration law are a dime a dozen: see this, this, this, or this.

But how many citizens know of this? They know nothing, of course: the law has nothing to do with them. They can feel free to demand 100% compliance with the law, because they will always be 100% compliant. All they have to do is breathe. It’s pretty easy to follow the law when you have to do nothing. How can you demand people follow the law when you yourself have no idea what the law demands, and you yourself don’t have to do anything to comply with it?

I am making no claim to perfection here. As a Malaysian, I have no idea what laws the foreigners living in my country have to comply with. When people ask me about how easy it is for foreigners to live in Malaysia, all I can say is “Well I saw a lot of them in my junior college so I think it’s pretty easy to come in”. I honestly have no freaking idea what our visa laws are; I have no reason or incentive to, because by definition, it is impossible for me to ever break the law!

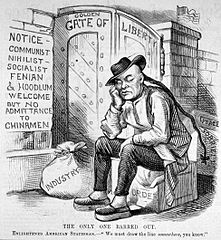

Claims that “Well, my ancestors followed the law” ring pretty hollow. After all, what laws did your ancestors follow? In the case of most Americans, their ancestors immigrated legally because all you had to do to immigrate was not be Chinese. If by definition it is impossible for you or your ancestors to have broken the law, then it is pretty rich of you to insist that you know exactly what laws others should comply with. Yet people often pretend they know exactly what the laws are, and blame the victims of these abusive laws for not submitting to their unwarranted punishment.

What’s good for the goose is good for the gander: if you want people to prove their loyalty and knowledge of your country by passing a test, then why don’t you subject yourself to that same test? Why not? Didn’t your schooling prepare you for that test?

If millions of ordinary people can waste 20 years of their adult lives waiting for government permission to pay rent and apply for jobs, why not you? What makes you so special? Isn’t it unfair to others who did wait those decades in line, who actually complied with the bullshit hoops your government made them jump through? Your ancestors didn’t jump through those hoops — so don’t you owe it to them to follow the law on their behalf?

And so on you go, railing against “amnesty”, even though there’s a good chance if you are American that you are only here today thanks to an amnesty your ancestors arguably didn’t deserve. I refer, of course, to that time some of your ancestors took up arms in violent rebellion against the lawful government of the United States, and were rewarded with an unconditional amnesty for their trouble.

At the end of the day, there is nothing that makes sense about most immigration laws. A handful of restrictions actually target terrorists, criminals, or contagious disease carriers. The rest of these laws just treat people who want to pay market rent for a safe home and the chance to earn the market wage for honest work as though they are criminals for doing the same things as everyone else. There is no sense in treating a minimum wage cook like a cutthroat, and there is no justice.

The real question isn’t what part of illegal don’t I understand; I’m well aware that, at least far as my own country goes, I don’t understand, because I have no reason to! No matter how many laws I break or how many wrongs I commit, I’ll always be in compliance with Malaysia’s immigration laws.

The real question is, what part of “illegal” do you understand at all? You don’t understand any of it. You don’t know what it’s like to be worried that accidentally working one extra hour a week this semester might mean that you’ll get deported. You don’t know what it’s like to earn pennies a day, banned from earning the dollars which your hard work could easily earn you because this year, only 23 people from your country of millions will be given work permits.

The persistence in which people pretend that complying with the law is no burden, that if their ancestors could do it then so can anyone else, truly boggles the mind. Laws which ban parents from paying to put a roof over their children’s heads and ban dutiful children from sending home money to care for their aging parents criminalise the virtues we so often commend to ourselves. What can this be, if not hypocritical injustice? Let me ask you — what part of “immoral” don’t you understand?