I was lucky enough to personally be in the audience earlier this week when guest blogger Bryan Caplan and software entrepreneur Vivek Wadhwa made the case for open borders at the Intelligence Squared debate on the motion “let anyone take a job anywhere“. Bryan and Wadhwa were up against Ron Unz, an American conservative intellectual, and Kathleen Newland, a migration policy wonk opposing the motion. You can watch a video of the full debate, read the transcript, or see our page on the debate and related links. The IQ2 organisers polled the audience before and after the debate on support for the motion; the winner was the one who moved the needle the most. No prizes for guessing how I voted.

Still, I was surprised at how much the polling going on favoured the motion; a plurality voted for it, 46%-21%, with another third of the audience undecided. The restrictionist side more than doubled their vote share to a solid plurality of 49%-42% by the end of the debate, with another 9% still undecided. The hypothesis which makes the most sense to me, which I think a lot of folks, including Bryan, subscribe to is that a good deal of the audience going in did not fully appreciate the gravity of the motion: this isn’t about moving from closed borders to cracking the door open an inch. This is about truly liberating the workers of the world from the chains which keep them locked up in the country they happen to be born into. A relatively naive pro-immigration person going into the debate could well have voted for the motion initially, and realised after the debate that they may want a slightly more liberal policy, but nothing close to open borders, and voted accordingly then. Overall, I am heartened that almost half the audience remained in favour of open borders even after hearing out the case for and against; I’d rather have 42% who strongly favour open borders in full knowledge of the case for and against, than 46% who think it sounds good but aren’t sure what the case for either side might be.

I am hardly an unbiased observer, but I felt Bryan’s opening and closing statements summarised well the best of the case for open borders: closed borders oppress innocent people. They treat people like enemies of the state simply because they were born in the wrong country — something they had no choice in. This is both manifestly unjust and incredibly inefficient. The world is losing the fantastic talents of billions, which could be put to so much better use outside the countries they are trapped in by happenstance.

Having said that, I did enjoy the other side’s arguments. Although I was hardly persuaded by them, I felt both Unz and Newland very clearly crystallised almost every single argument, short of outright bigotry, that I’ve heard against open borders. Unz played a very effective restrictionist bad cop to Newland’s “we can let more in, but we can’t open the borders” mainstream liberal good cop. Unz trotted out a bunch of familiar populist right-wing arguments: immigrants depress wages; they’re scheming welfare parasites; and they will only be a boon for wealthy capitalists. Newland trotted out all the familiar left-wing arguments: admitting immigrants imposes an obligation on government to care for them and government’s resources are not unlimited; every government has the authority to impose its own restrictions on immigration as it sees fit; it is irresponsible to outsource immigration policy to private citizens like employers.

Wadhwa was the only debater who disappointed me. He and Bryan came in seeming to have agreed to specialise; Bryan would cover the arguments for low-skilled immigration, and Wadhwa would speak to the arguments for high-skilled immigration. This arrangement turned out to be ineffective, I think largely because hardly anyone can oppose open borders for high-skilled workers: every single argument made by Unz and Newland was really against open borders for low-skilled workers. Wadhwa thus didn’t really have much to say other than repeat all the points for what, in my mind, is the virtual slam dunk of high-skilled immigration.

Having said that, one thing that was new to me that night was finding that Wadhwa really favours open borders. I know I wasn’t the only one who, when I heard the line-up, wondered why Wadhwa was speaking, when all his prior activism has focused on high-skilled immigration. People standing up for the right of the privileged, educated classes to move freely around the world are a dime-a-dozen. But try talking to them about immigration from anyone else, and these people’s positions often change either to apathy or outright restrictionist antipathy. From his comments during the debate, Wadhwa showed he is on on side of open borders for all, and rejects all the apocalyptic predictions which Unz so ponderously repeated that night. As Wadhwa so simply put it, “if an employer thinks that this Mexican gardener is more qualified to do this job than someone else they can hire locally, let them do it.”

My favourite moment of Wadhwa’s was when he took to the stage for his opening statement and showed himself clearly speechless at Unz’s demagoguery: I’ve read Unz’s work, as have Bryan and Wadhwa, and we know Unz is far more intelligent and nuanced than the caricature of restrictionism he appeared that night. Unfortunately, Unz’s demagoguery clearly worked. All you have to do is trot out the laundry list of myths about the evils of immigrants, and dramatise the scenario out of any proportion to the actual facts. Unz repeatedly declared that open borders would “convert America’s minimum wage into its maximum wage” — a prediction I’d gladly bet with Unz on, if only we could somehow open the borders. Economists have repeatedly found that more immigration actually has hardly any impact on wages for most workers, and may even boost low-skilled natives’ incomes. Even if you multiply the most pessimistic estimates of immigration’s effects on wages several times over, you cannot come close to driving wages down to the level of the minimum wage.

Unz knows none of this; he happily opened with the cheerful declaration that he doesn’t know anything about economics. But populist demagoguery is quite an effective debating tactic, especially when you’re dealing with a non-technical audience. Unz harped on how open borders would cause class warfare, ostensibly because a massive influx of foreign labour would harm native labour tremendously, to the benefit of capital. But the economist consensus is quite clear: Unz is wrong. As one economist, Ethan Lewis (who, full disclosure, is a former teacher of mine) has said: “Calculations often include native ‘capital owners’ as additional short-run beneficiaries, but there is ample theoretical and empirical support for the idea that such benefits do not last beyond a few years – the short run really is short.” Moreover, Lewis has looked at how industrialists actually respond to inflows of foreign labour — and he has found that they respond by cutting back on their investments in capital and investing more in low-skilled labour, in turn driving up low-skilled natives’ incomes!

Unz’s arguments are superficially appealing, but they simply cannot withstand scrutiny when you look into the ideas and thinking which Unz purports to back him up. I thought Unz did exactly what a debater looking to persuade people to the restrictionist side should do: choose what people are likeliest to believe, and hammer away at it. But convincing as he might have sounded, I think that Newland likely was the one who won the debate for their side.

To be fair to her, Newland is no lover of closed borders: she’s an advocate for more liberal immigration policies and clearly cares for migrants. But she was the speaker who took the positions that I feel appeal the most to any layperson in the mainstream who is asked to consider open borders: well, it’s good to help poor people by letting them in, but we have to be careful to ensure we don’t admit too many, since it creates an obligation for us to care for these people, and we don’t have limitless resources. She elucidated these positions clearly. I also felt that she made perhaps the most frank and revealing statement of the evening: when asked if she favoured government discrimination against the foreign-born, she responded: “I think our governments are obliged to discriminate in our favor“. As she so clearly says, the case against open borders rests in large part on denying the assertion Bryan made in his opening statement that banning foreigners from seeking honest work is no different from banning women, Jews, or blacks from seeking honest work. It’s different, you see: discriminating against women, Jews, and blacks is wrong. But it is so right to discriminate against foreigners.

Much to my dissatisfaction, after opening statements, the debaters spent a lot of time arguing about whether a minimum wage should apply to immigrant workers, and if so, how high should it be. Here, Bryan was alone in insisting there was no need to set such a precondition on opening the borders. The rest of the panel agreed that the US ought to raise its minimum wage, and spent a good deal of time going back and forth about how this impacted the motion. To me, this question is entirely irrelevant, and I think Bryan could have tried harder to shut down this red herring by following up on a point Wadhwa made: the debate is about whether we should let anyone take a job anywhere. The debate has nothing to do with other labour market regulations. Any government has the authority to regulate its domestic labour market. Whether those regulations are appropriate or need amending is a completely different issue. All Bryan and Wadhwa are saying is that governments do not have the authority to discriminate against foreigners in the labour market — to impose one set of labour laws on foreigners that do not apply to natives.

To put it differently, there are different laws governing the labour market in the US, the UK, Bangladesh, and Brazil. But nobody’s saying that they all should have the same set of labour laws, the same minimum wage. The point of open borders is that people who want to move out of one labour market, out of one set of labour laws and regulations, and into another one, should be allowed to. People should be allowed to seek work anywhere, and people should be allowed to hire anyone from anywhere, in compliance with all the same labour laws that apply to native workers. Restrictionists in Unz’s camp may favour a high minimum wage to price unskilled foreign workers out of the labour market — but that’s a very different kettle of fish from favouring the use of tanks and gunships to threaten unskilled foreign workers with violent force. The scope of the motion was fundamentally about ending the global war on immigrants — not raising the US minimum wage.

One thing I liked about how the IQ2 moderator, John Donvan, set up the debate was that he made clear open borders is already being tried in the EU, and can readily be accomplished on a larger scale today via multilateral open border treaties. I thought it quite funny how Unz and Newland argued that we shouldn’t count this a success for open borders, because EU policy poured aid into poorer EU countries prior to opening the borders in hopes of dissuading economic migration. They made it sound like the EU only opened its internal borders once every country had more or less attained a similar level of economic performance. But EU countries range in per capita income (adjusted for purchasing power) from the $15K-$20K range (for countries like Bulgaria, Romania, and Poland) up to the $40K-$50K range (for countries like Germany, the Netherlands, and Austria). The fact of the matter is, as Bryan and Wadhwa pointed out, that none of the catastrophes which Unz and those of like minds have insisted are sure to happen under open borders actually happened in the EU. And Mexico has a higher per capita income than Bulgaria, mind you!

After the debate, I felt that the organisers had actually put together a fantastically representative panel:

- Bryan, the open borders cum free market radical

- Wadhwa, the open borders moderate

- Unz, the restrictionist doomsday prophet

- Newland, the mainstream liberal open borders skeptic

Each person represented a distinct side of the debate. Unfortunately, because of disagreements on rather irrelevant points (like the level of the minimum wage), Bryan and Wadhwa sometimes found themselves having to disagree. Moreover, Unz and Newland were careful to make points which complemented each other; even though right- and left-wing populism rarely agree on much elsewhere, it’s hardly surprising that they tend to agree on immigration. Both left- and right-wing restrictionists share the belief, so clearly articulated by Newland, that government is obliged to protect people from competition in a fair market by use of tanks and battleships — by treating innocent people who happen to have been born in another country as if they are armed, invading armies. It was not a huge surprise to me that the audience, by a slight margin, felt more persuaded by Unz and Newland, even if their facts and assertions were often way off base, especially in Unz’s case.

Newland dealt more in moral arguments that evening than she did in facts, which made her the more formidable opponent, even though you can certainly say the moral case for open borders is a slam dunk. Newland stated simply that people feel that admitting immigrants is to assume some sort of responsibility for them, and this makes it impossible to admit everyone, since our resources are not limitless. In other words, governments have an obligation to provide the same level of welfare and benefits for everyone in their territory.

Newland also harped on the claim that governments have the fundamental authority to set any immigration policy they like, no matter how unjust or arbitrary this policy may be. She never backed this up, moving on to argue that it’s undemocratic and unjust to place immigration policy in the hands of private citizens like employers. While I agree it would be concerning if we allowed private companies or citizens to grant citizenship to anyone they like, that clearly has nothing to do with open borders: open borders is not open citizenship.

Newland’s arguments amounted to assuming that governments have the authority to discriminate against foreigners in any way they like because foreigners are not citizens. This is extreme; surely Newland and I imagine Unz would draw the line at allowing the government to impose the death penalty on foreigners who illegally immigrate. But Bryan, Wadhwa and I would move that line a little more: we draw the line at allowing the government to force its own citizens to discriminate against foreigners in hiring and firing decisions. We draw the line at forcing people to face arbitrary rules and punishment simply to hold down their job or live with their families. Governments can discriminate against foreigners in all other sorts of ways; as Bryan proposed, governments can even charge foreigners a fee or surtax for immigration. If it is unjust to murder someone for the crime of being born in the wrong country, it is also unjust to use armed force to deprive them of a job they are qualified to do.

The most effective counter-argument from Bryan and Wadhwa that evening was their concrete illustration of how so many of the citizenist and doomsday-type arguments which Unz and Newland used were old replays of the arguments used against allowing blacks or women into the labour force. The labour market wouldn’t be able to cope. Capital would exploit the new workers at the expense of the old workers, who’d be laid off or see wage cuts. It wouldn’t be fair to existing workers, who society and its institutions have obligations to. None of these are convincing reasons to ban blacks or women from joining the labour force; neither should they convince you that it’s right to ban someone from working somewhere just because of where he was born.

Bryan also pointed out the moral tension in Newland’s seemingly compassionate argument. Her insistence on using armed force to keep out immigrants if the welfare state isn’t able to accommodate them seems self-defeating: if someone wants to do a job, because it makes them better off many times over, why ban them from doing it at the point of a gun? If this person is one of the most economically oppressed people alive today, and if leaving their current job is literally a matter of life or death, why are we so happy to ban them from taking a job that multiplies their income by leaps and bounds, saving them from a life risked working on the floor of a sweatshop that might just collapse one day? Even if we find it unpleasant to witness poverty in our country, how is it anything but cruel to use armed force to keep out those poor people who want to come here simply to better their condition with honest wages?

Ultimately, I think the main elephant in the room that wasn’t quite adequately addressed was the point Newland made about citizenism: that governments are obliged to discriminate in favour of citizens. I think that is quite true, yes, in matters of national security, as she herself said. But the labour market is not a matter of national security any more than the agricultural market or information technology market are. Those markets are surely sensitive and of national importance, which is the excuse the US government uses to impose farm subsidies and import tariffs, and the excuse it uses to ban the export of some encryption technologies. But the government imposes such restrictions selectively and only where warranted. It does not impose a blanket ban on trade. Let’s put aside the question of whether those other restrictions make sense; the point is, there is far more of an open border when it comes to markets of unquestionable national importance like farming and information security, than when it comes to labour. As Wadhwa said, it is crazy that we are having a debate about whether an employer should be allowed to hire whoever he likes, when the only disqualifying factor we can think of is the candidate’s country of birth. If the foreigner isn’t a terrorist or public health threat, what business is it of the government’s to ban its citizens from hiring him?

The citizenist point of view clearly resonated; it came up frequently in the audience Q&A. More than once, someone stood up to demand to know why the US should open the borders at all when it is beset by domestic problems. Nobody on stage seemed to clearly grapple with this to me. I think I can imagine what Bryan would have said if he wanted to thoroughly grapple with this thinking, but his preferred total rejection of all citizenist ideas is not, I imagine, a great rhetorical strategy, especially when you have limited time to make your case.

Yet, in my mind, this citizenist thinking is the most important barrier to break down. Sure, governments have obligations to their citizens that they do not have to foreigners. But governments do not have the obligation to ban foreigners from competing with citizens in a fair marketplace. What purpose does it serve to use armed force against innocent civilians? To call Unz’s apocalyptic scenarios if we open the borders “unrealistic” is too kind. There is no prima facie case for banning an innocent person from taking whatever job he can get in the marketplace in any country of the world. There is no reasonable basis for treating someone who wants to work in a restaurant kitchen or get an education as if they are a common criminal, or worse, an armed enemy of the state. Governments have the authority to impose immigration restrictions — but for the sake of the common good and in response to a clearly defined threat, not for the sake of simply “protecting” citizens from fair competition in the marketplace.

The organisers of the IQ2 debate billed it as a thrilling contest of wits and persuasion. As you can tell from how much space I’ve devoted here to discussing the debate, I’m certainly happy to give them that point. Although I can’t say I’m happy that open borders “lost” the debate, I am glad to have heard some of the best arguments that both sides offer, and glad that a broader audience was able to hear them too. The case for open borders rests on debunking the economic myths and muddled moral thinking which make closed borders so appealing to many. The open borders side might not have won this time, but we gave the closed borders side a good run for their money — and I look forward to seeing the progress we can make here the next time around.

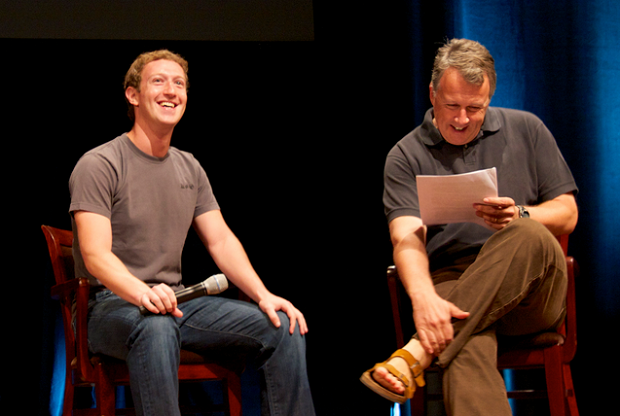

Photo credit for picture of Bryan Caplan and Vivek Wadhwa at the debate: Samuel Lahoz, Intelligence Squared.