My recent post, “How Would a Billion Immigrants Change the American Polity?” attracted a fair amount of attention, most recently an article in the Washington Examiner with the deliciously intriguing headline “Open Borders Would Produce Dystopia, says Open Borders Advocate.” The headline, which somewhat misrepresents the more balanced article by Michael Barone that appears beneath it, is a crude caricature yet in its way bracingly lucid, for it points to what I think this debate has clarified, namely, that the chief difference between open borders advocates and their critics lies not in what they foresee but in how they assess it. As Niklas Blanchard puts it, “this is purely an emotional dystopia for (wealthy) people of a certain temperament…Smith‘s piece is… maximally grating to the ‘social justice’ crowd” (Blanchard, however, goes on to praise me for rigorous adherence to demand and supply logic in making projections and concludes that he finds my analysis “rather beautiful”– thanks!) but it still features doubling world GDP and ending world poverty and the rest of the good features that open borders advocates want in the world they’re trying to bring about. The disagreement is more about values than facts, more normative than positive.

I’m very grateful for all the feedback, which was not only abundant, but in many cases, pretty astute! To express my gratitude, I’ll reply to some of it. Probably not many of those who responded to the first “billion immigrants” post will ever read this one, but it seems right to have a response, so that anyone who cares to look, knows that I’m listening. (I already engaged a bit at OBAG.)

One point that was raised privately by my colleagues here at Open Borders is that the migration of a few billion around the world (“a billion immigrants” refers, very roughly, to the projected immigation to the US alone) might not happen as a steady flow, but rather, as a response to crises, such as civil wars, economic depressions, natural disasters, anthropogenic global warming, etc. Or perhaps, more positively, in response to dramatic economic booms, the emergence of new cultural meccas, or religious quests to establish new Jerusalems, such as brought the Puritans to North America and the Mormons to Utah. The Syrian civil war has produced over 4 million refugees, almost one-fifth of Syria’s pre-war population. That’s tragic, but much better than the experience of the Jews on the MS St. Louis, many of whom died in the Holocaust after an attempt to emigrate from Nazi Germany was thwarted because no one would permit German Jews to immigrate. For some, this may mitigate the implausibility of a billion immigrants coming to the US. I don’t find a billion immigrants prima facie implausible, but this “punctuated equilibrium” version of the scenario seems at least as likely as a steady flow version.

Alex Nowrasteh also pointed out that Americans might respond to a billion-immigrants scenario with more aggressive “Americanization” policies, such as were adopted in the USA around the turn of the last century, about which he wrote an interesting and informative Cato blog post. His take is mildly negative, but I would regard an Americanization campaign led by civil society as quite benign, and even an aggressive, government-subsidized, mildly intolerant Americanization campaign would be very benign compared to current migration restriction policies. However, I don’t know what “Americanization” would mean today, because American culture seems so fractured that I don’t see much to assimilate to. I love listening to bluegrass gospel, which to me represents the very soul of America, yet there is another America where San Francisco liberals would feel at home, and which to me is more hostile and alien, not than Iran perhaps, but certainly more so than many a Christian church in Africa, Russia, or Latin America. I don’t know what Americanization would mean today.

Big Think has a pretty good article about my article, entitled “Thought Experiment: What if the US Had 100% Open Borders?” The summary of my hypothetical is pretty astute, though I might object slightly to this:

What’s most interesting is how Smith conjures a scenario out of which American constitutional democracy becomes so destabilized that it collapses beneath its own weight. We’d be looking at a new world order and an American polity unrecognizable compared to the present.

“Collapse” is the wrong word. What I projected (again, very tentatively: no doubt these disclaimers become tedious, but I want to prevent anyone from investing too much epistemic confidence) is “a new world order and an American polity unrecognizable to the present,” but the path to it would be a kind of swift and mostly peaceful evolution, not any revolutionary collapse. And I’m not sure, in an age of runaway judicial activism, what the phrase “American constitutional democracy” means, anyway. (The phrase “American constitutional democracy” would have had a clear meaning in 1900 but not in 1950. The phrase “American democracy” would have had a clear meaning in 1950, and to a lesser extent in 1980, but not today.) Which leads to my other objection to the piece:

For many people, that might sound like a reason to scrap a 100 percent open-border policy. Smith is not one of those people. He’s got a bone to scrap with American politics and wouldn’t mind it turning into collateral damage amidst the rush of a brave new society [followed by my comparison of modern constitutional law to the late medieval Catholic theology of indulgences and my call for a kind of Lutheran Reformation to overthrow it.]

I can see how someone who read only that article might get the impression that my main reason for supporting open borders is my indignation at judicial activism. This is a case of being misunderstood because one reaches unanticipated audiences. I was writing for regular readers of Open Borders: The Case, who already know my main reasons for favoring open borders. That post reached a wider audience and so caused confusion. A quick review of my position may help.

My major reasons for supporting open borders may be classified into the deontological and the utilitarian:

Deontological. Human beings have rights, arising from their own natural telos, which we must respect. By “must” I mean something close to an absolute prohibition: I would tend to say that one mustn’t torture an innocent child even to save a great city from a terrorist attack. However, life doesn’t generally present us with such stark test cases. More often, we are tempted to violate human rights to prevent amorphous threats clothed in bombastic rhetoric. Thus, Nazi soldiers were driven to terrible crimes by spurious fears of Malthusian national impoverishment or starvation if Germany didn’t acquire sufficient Lebensraum, and even more spurious fears of a conspiracy of international Jewry against the German race. Astute intellectuals may see through such propaganda, or even refute it, but for the ordinary person, the key is to cling stubbornly to one’s humanity and the dictates of conscience, and refuse to commit crimes, no matter how vividly society makes you believe in the horrors that will come from not committing them, and no matter how propaganda stirs your passions to make you want to commit them. Now, migration restrictions involve doing terrible things to people. US immigration enforcement separates thousands of parents from their children by force ever year. European coast guards are culpable for a mounting toll of migrant deaths at sea, and so on. These things simply must stop.

We are not at liberty, as moral beings, to read through my “billion immigrants” scenario and think, “Hmm… Do we want that? No, we’d rather not.” In order to maintain migration restrictions, people who work for governments that represent us are doing things that must not be done. We are constrained by the imperative of human rights, constrained far more tightly than most in the West have yet been willing to admit to themselves. We are guilty every day that we tolerate the status quo. I won’t say, quite, that human rights imperatives demand open borders. (People have a right to migrate inasmuch as their practical telos requires migration, e.g., if it’s necessary to survival or earning a living, while in other cases there is a liberty to migrate in the sentence that no one else has a right to prevent migration by force. See Principles of a Free Society for details.) Rather, I doubt that any policy short of some kind of open borders simultaneously gives adequate respect for human rights and makes it incentive-compatible to obey the law. My “billion immigrants” scenario isn’t like an item on a restaurant menu, which a patron may choose, or not, according to pure preference. It’s more like a forecast of how the courts are likely to treat a robber if he does his duty by turning himself in to the law. Of course, such a forecast might give a robber self-interested reasons to turn himself in– the jail cell may be warmer than his hideout in the woods, with better food; and if he turns himself in he’ll get a shorter sentence– but these are secondary. I hope readers will find the prospect of a billion immigrants not too unpleasant, and that it will encourage people to do the right thing, but if the prospect is frightening, still we must stop deporting people, and prepare ourselves for the consequences.

Utilitarian (universalist). My other major reason for supporting open borders is that it is the best way to promote the welfare of mankind. This belief is based primarily on economic analysis, and more generally is derived from my expertise in international development. As far as I can tell, it seems to be broadly shared by others with similar expertise who have studied the question. Even a thinker like Paul Collier, an expert in international development and a critic of open borders or greatly-expanded immigration, does not so much dissent from the proposition that open borders is optimal in utilitarian-universalist terms, as reject utilitarian universalism as a mode of ethical analysis.

But how can open borders be optimal from a utilitarian-universalist perspective when my “billion immigrants” scenario is so dystopian? Simple: it isn’t dystopian, except from a certain historically myopic and rather unimaginative American/Western perspective that takes “democracy” as the magic word distinguishing everything good from everything bad, without thinking deeply about what the word means. My “billion immigrants” scenario does not involve widespread deprivation of real human goods like food, art, material comforts, family life, freedom of conscience and worship, health, education, truth, adventure, etc. On the contrary, it would seem to involve greater enjoyment of those things by almost everyone, native-born and foreign-born alike. The most dystopian aspects of the scenario, e.g., “latifundia” paying wages that look like slave labor to Americans, aren’t novel features of an open borders world, but features of our present world, which open borders would simultaneously move and mitigate. In soundbite format: open borders would bring sweatshops to America, but they’d be more humane and pay better wages than the sweatshops in China and Indonesia that would mostly vanish as their workers found better lives abroad. Meanwhile, for many an Indian or African peasant, even a steady job in a sweatshop is the end of the rainbow. (Also see John Lee on how open borders would abolish Bangladeshi sweatshops.)

How do these deontological and utilitarian-universalist meta-ethical* perspectives interact? A crude but helpful model is to think of ethical problems as analogous to the consumer’s problem in economics, with the utilitarian-universalist goal of maximizing the welfare of mankind serving as the “utility function,” while deontology provides the “budget constraint.” Deontology dictates that there must be no violence except in self-defense or retaliation against violence, plus a few other things like no lying, no adultery or (I would add, more controversially) premarital sex, no abandoning one’s spouse or children, no non-payment of one’s debts, and so forth. (Just because deontology dictates that it’s wrong doesn’t mean it should be illegal, e.g., most private lying is wrong but probably shouldn’t be punishable by law.) Within the constraints imposed by deontology, we can consider which courses of action are most conducive to promoting the welfare of mankind, and pursue them. At this point, if I were writing a treatise on ethics, I would segue into virtue ethics, explaining how contributing to the welfare of mankind involves the pursuit of all sorts of excellence; but the pursuit of excellence in turn requires certain traits or habits, such as courage, justice, prudence, temperance, faith, hope, and love, which we call virtues; and how, once acquired, we recognize that these virtues are not only the key to effectiveness in all sorts of situations and to doing any real good in the world, but are more desirable in themselves than any merely material pleasures, or any praises from multitudes. But for the present, it suffices to establish that deontology and utilitarian-universalism both point the way to open borders. The need to respect human rights and the moral law, and the desire to promote the welfare of mankind, are why I support open borders. That it might destabilize the judicial oligarchy that currently misgoverns the US is just a small side-benefit.

Next, I’ll turn for a moment to what stands out as one of the least astute reader responses to the article (whom I’ll leave anonymous, but it’s at Marginal Revolution):

Am I the only person who thinks this sounds really, really bad? Transition from republic to empire? Rich people employing almost-slave laborers? No social safety net? No more ‘one person, one vote’? Lots of gated communities? Destruction of the living standards of native-born Americans?

Sometimes my “billion immigrants” scenario seems to have served as a kind of Rorschach test. In the mass of detail, people saw whatever they were predisposed to see. I didn’t predict a “transition from republic to empire.” Rather, I used Rome’s transition from republic to empire to illustrate how a superficial continuity of a polity could be consistent with substantive transformation. I would expect open borders to lead to substantive transformation of the American polity, combined with superficial continuity, but the substantive transformation isn’t aptly described as “transition from republic to empire.” A more astute reader might have noticed that at the end of the transition, my open borders scenario looks rather like the Roman Republic in its heyday, say around 200 B.C., with a well-armed citizen minority ruling fairly beneficently (for one has to grade historic regimes on a very generous curve) over a large and diverse subject population, who to considerable extent consented to Rome’s/America’s rule.

However, according to a post on BMW Aktie kaufen, the “transition from republic to empire” misconception is somewhat understandable. What’s baffling is the impression that I predicted “destruction of the living standards of native-born Americans.” On the contrary, I predicted continuous, surging economic growth, an enormous rise in the stock market, major appreciation of home values, lots of business for professional workers, government handouts and subsidies to the native-born, cheap drivers, cheap nannies, cheap domestic servants… basically, a bonanza for native-born Americans, to the point where many of them become a rentier class whose greatest complaint is the ennui of idleness. Admittedly, I also foresaw that some natives would see their wages fall, but the loss would be more than made up for by other income sources. I also suggested that threats of revolt might lead to the conscription of natives into a domestic police force, but while some might find that unpleasant, it’s not a case of falling living standards. It’s one thing to say that I’m wrong about all this, and that the impact of open borders on most native-born Americans would actually be the destruction of native-born Americans’ living standards, perhaps because restricting immigrants’ voting rights would prove politically infeasible, and immigrant voters would degrade institutions and/or redistribute resources to themselves via the ballot box. But this commenter seems to think that I predicted the destruction of natives’ living standards. I wonder how often writers get blasted as having said the exact opposite of what they actually said.

I found this comment by Jorgen F. a pithy characterization of me:

He is convinced that only white people in the West can create a decent society. Hence America should create a shortcut for the rest of the world.

You know, America should care more for non-Americans than for Americans. It is so beautiful.

That’s not far wrong, though of course I don’t think the capacity to create a decent society has anything to do with race. I think it has more to do with 2,000 years of cumulative Christianization (in which story, historical episodes like the High Middle Ages when parliaments and universities and the common law appeared, the Renaissance, and the benign early Enlightenment, were chapters). Nor is high economic productivity synonymous with “decent society.” But I do think that Western societies are going to be nicer places to live than most of the rest of the world for a long time, so I’d like to see a lot more people get the chance to live in them. And of course we should care more about non-Americans than Americans, because there are a lot more of them, just as we should care more about non-Russians than Russians, non-Chinese than Chinese, etc. That said, since I propose to tax immigration to compensate natives for lost wages (DRITI), I can actually make a citizenist case for open borders too. I think open borders can be designed to benefit almost all native-born Westerners, without much reducing the benefits to the rest of mankind. But the main reason for opening borders is to respect human rights and end world poverty. When I worked for the World Bank, I was proud that its motto is “Our dream is a world free of poverty,” and in advocating open borders, I’m still being faithful to that vocation.

A comment by E. Harding that:

This is precisely the kind of atomism that anti-libertarians decry.

is directed less at me than at fellow commenter Chuck Martel (who had given reasons why he shouldn’t care about most of his fellow Americans), but E. Harding may also have had me in mind. As I argued in a post some time ago, I’m not ultimately very individualistic in my view of human nature and human happiness. Human flourishing almost always has a communal character, and this insight is necessary to fully appreciate the evil of migration restrictions, which inevitably lead to deportations and the forcible separation of families. “Communitarian” arguments against open borders generally boil down to “we’ll protect our communities from possible disruption by shattering your communities by force.” Open borders would allow families and other communities forcibly kept apart by migration controls to come together.

One of the comments I found most horrifying was by Horhe:

I do not understand how anyone can read [Smith’s article] and some of the other writings online and offline that doubt the wisdom of open borders (I particularly liked “Reflections on the Revolutions in Europe” by Christopher Caldwell) and still think that this is a good idea.

If the closed borders crowd are wrong and you do it their way, then nothing is lost and you can open the borders some other time, when people might be more easily absorbed because of lower disparities. But if they are right, and the open borders people get their way, then there is no going back to the way things used to be, without a bloody ethnic war. Which, come to think of it, might actually be started by the newcomers, who would be hurrying history along.

Now, I consider myself a Burkean conservative as far as conscience permits; I always advocate due regard for the precautionary principle; and in my vainer moment I sometimes think that Chapter 2 of my book The Verdict of Reason is a defense of tradition worthy of G.K. Chesterton. But there are fundamental principles of right and wrong that are deeper and more sacred than any human traditions, and in the face of which any mere precautionary principle must give way.

When I was a passionate Iraq War advocate some years back, I never forgot that in supporting the war, I was making myself complicit in a lot of killing, including some killing of innocent people. I thought the price was worth it, to abolish one of the two (Saddam Hussein vs. North Korea was a close call) most detestable totalitarian tyrannies on earth, but it was a great moral burden. Migration restrictionists, too, have a duty always to remember the human toll of border controls: the people stuck in poverty; the families forcibly separated. Maybe, even if they contemplated this frequently, some would still conclude that migration restrictions are a tragic necessity. But to say “nothing is lost”… the mind boggles in horror! How is such callousness possible?

I would not have enjoyed explaining to a bereaved Iraqi mother why I had supported the war that had just killed her son. But I could have done it. I would have spoken of the horror of totalitarianism, the transcendent moral importance of living in truth, and the value of setting a precedent that would make future murderous dictators doubt their impunity. I think many an Iraqi mother, after what her country had been through, would have understood me. Poll evidence tends to suggest that, while by 2005, the Iraqis already wanted the US out, most thought the hardships of the war and transition were worth it to be rid of Saddam.

Migration restrictionists should put themselves to the same moral test, taking responsibility for the vast human toll of the policies they advocate. How would you explain to a mother who is being deported from her children, not to see them again for a decade perhaps, or even forever, why her life is being thus shattered, when she never harmed anyone, never did anything to the Americans who are doing this to her, except clean their houses, or pick grapes and oranges for their table? There might be arguments that would mitigate the offense, but to say that “nothing is lost” since we can always stop doing these horrible things “some other time”… can such a detestable blasphemy, at such a moment, be imagined?

My imagination conjures a scene in which Horhe and his ilk are compelled by some Ghost of Christmas Present to watch, invisible and helpless, as some weeping mother is seized and dragged away from her terrified and uncomprehending children. Their humanity awakened, they plead with the Ghost: “Spirit, please, let them stay together!” And then the Ghost, in the appropriate tone of sneering contempt, quotes their own words back to them: “Later, when people might be more easily absorbed because of lower disparities, we’ll let families like these stay together. Nothing is lost by waiting.”

The answer to Horhe is: Repent! Find the ugly place in your soul from which such heartless thoughts arise, and kill it!

But sorry for getting so heated. I’m not living up to Bryan Caplan’s praise of Open Borders: The Case as a “calm community of thinkers.”

Thiago Ribeiro’s response to Horhe is also good:

If people who were against vaccines, fertilizers, abolishing slavery, abolishing witch trials, eliminating Communism, emancipating the Jews (…) nothing would be lost. Those things could have been dealt with later… Status quo bias at its more stupid.

Exactly. Any reform in history could be opposed on such pseudo-Burkean grounds. And contra “nothing would be lost,” vast losses are incurred every single day that we fail to open the borders to migration.

I found the last bit of this comment by Christopher Chang gratifying:

Sweden… for all practical purposes [has] already been running this experiment for more than a decade, and there still is supermajority citizen support for continuing the experiment…

Of course, most open borders advocates are systematically dishonest and avoid talking about Sweden even after they’ve known about it for years, because the “experimental results” to date are much worse than their rosy projections. I’ve repeatedly told them that one of the best things they could do for their cause is advise the Swedes to adjust their implementation of open borders to be less self-destructive (support for the anti-immigration Sweden Democrats has skyrocketed from ~2% to ~25%, so the supermajority is unlikely to hold for much longer unless the government changes course), but they’ve been totally uninterested even though they’ve interacted with e.g. Singapore’s government in the past. Instead they continue to pretend their ideas are “untried” and might constitute a “trillion dollar bill on the sidewalk”.

Since revealed preference is far more informative than rhetoric, I’m sadly forced to conclude that they don’t actually care as much about increasing global prosperity as they do about harming ordinary Westerners they don’t like, even though some of them have done genuinely good work in other areas. (With that said, I hasten to note that Nathan Smith, the author of the linked post, is an exception who respects the principle of “consent of the governed” and has an excellent track record of intellectual integrity.)

In return, I can say that Christopher Chang’s comments have often alerted me to interesting immigration policy developments around the world. However, the claim that Sweden practices open borders seems a bit clueless. A recent NPR piece reports that “for decades, it had a virtual open-door policy for asylum-seekers and refugees.” Virtual. In other words, not an open borders policy, but simply a relatively generous policy. And only “for asylum-seekers and refugees,” which are only a small subset of all would-be immigrants. If you look at the official site about getting work permits in Sweden, it says (a) you need to get a job offer first, so you can’t just go to Sweden and start applying, (b) the job has to have been advertised for 10 days, so Swedes have a head start in applying for it, and (c) “the terms of employment offered are at least on the same level as Swedish collective agreements or customary in the occupation or industry,” thus robbing migrants of what for most would be their biggest competitive advantage: a willingness to work for much lower wages and in worse working conditions than Swedes. Sweden does seem to be fairly generous in its immigration policy, at least relative to other Western countries (a very low bar), but this isn’t open borders, not even close. (I suppose one could argue that the last condition is just immigrants being bound by Swedish labor law, but the point is that Sweden isn’t just making an open global offer for anyone to come to Sweden and making a living as best they can. Setting refugees to one side, it’s hard for most people to get in.)

Jason Bayz makes an interesting remark:

The essay is interesting because, unlike some politically correct libertarians, Smith does not pretend that his open borders experiment would lead to liberal nirvana. He’s quite open about the fact that it would kill things like “equality of opportunity.” Especially interesting is [the] paragraph [about] “gaps… where where representatives of the official courts feared to tread and a kind of anarcho-capitalist natural law would prevail”… Private law? A more traditional term would be Lynch Law. The Middle East would be an apt comparison for its tribalism, discrimination, importance of religion, and “private” settlement of disputes.

Readers have a right to wonder what my cryptic phrase “anarcho-capitalist natural law” was a placeholder for, and I suppose, to fill in the blank in their own way. Yes, lynching is an example of private law, but so are more benign things like eBay’s customer rating system, or in-between things like the private security companies whose logos appeared on every single house in a South African suburban neighborhood where I once spent the night.

I would also want to push aside the mere knee-jerk reaction to the phrase “lynch mob” and raise the deeper question of what is wrong with lynch mobs. I welcome practical objections to lynch mobs, such as that they don’t respect due process and often punish innocent people, or that they’re not even motivated primarily to prevent real crime but instead want to oppress minority communities. I would challenge the assumption, or resist the assertion, that lynch mobs are evil simply because they’re private, unauthorized by a “sovereign” authority. In US history, it may be the case that private law has been, on average, less just than public law, though that’s unclear, when you recall the injustices perpetrated by the US government against many Indian tribes, in upholding slavery, in the Prohibition era, in deporting peaceful immigrants, etc. But certainly the worst crimes of American lynch mobs don’t hold a candle to the crimes of the sovereign regimes of Nazi Germany, Soviet Russia, etc. I would suggest that violence should be judged by the same standard of justice, whether it’s done by “private” or “public” actors. The problem with lynch mobs is that they so often act unjustly, but as their injustices seem to be much less than those perpetrated by bad governments, our horror of them out to be less than our horror of bad governments, in the same proportion.

As for the suggestion that there is an “apt comparison” to be made between an open borders America and the contemporary Middle East, the obvious rebuttal is that the Middle East is mostly Muslim, whereas an open borders America would almost certainly be majority or at least plurality Christian, since Christianity is the world’s largest religion with over 2 billion believers today and an expected 3 billion by mid-century; Christians would probably be more attracted to the US as a migration destination; and many immigrants of non-Christian origins would assimilate to America’s predominant religion. I’ll assume (since it’s rather obvious but would take a lot of space to explain) that most readers understand that Christianity and Islam are profoundly different, and that religion is a major factor determining the differences between Muslim societies and Christian societies, including those in western Europe, where Christian belief and practice have recently waned, but where the nature of the societies is largely defined by the moral and institutional legacy of Christianity. An open-borders America wouldn’t be majority-Muslim, so it wouldn’t resemble the contemporary Middle East; it’s as simple as that.

Commenter Mulp makes a historical objection to my assumption that an open borders America would restricting voting rights for immigrants and thus end majority rule:

“If open borders included open voting, US political institutions would be overhauled very quickly as political parties reinvented themselves to appeal to the vast immigrant masses, but I’ll assume the vote would be extended gradually so that native-born Americans (including many second-generation immigrants) would always comprise a majority of the electorate. …”

Hey, why not simply discuss US history from 1790 to 1920 when the US had open borders except in California?

It’s true that from 1790 to 1920, the US had open borders and also open voting. But that open borders America never had nearly as large a share of migrants in the population as the economic models predict that a future open-borders America would, and the US government wasn’t an engine of economic redistribution then. I think my scenario is a better forecast of what an open borders future would look like, than an extrapolation from the experience of the US from 1790 to 1920.

Commenter Fonssagrives writes:

If the writer thinks “All men are created equal” is idealistic twaddle, then why do Americans have any moral obligation to let 1 billion foreigners into their country?

This is an interesting objection. It’s symptomatic of the psychic damage that the cult of equality has done to American minds. It invites a longer answer than I’ll make time for at present, but as a placeholder for that longer answer: people are very unequal in their talents and virtues; and treating them unequally is often prudent; but it doesn’t follow they should get unequal weights in a social welfare function.

Jer writes:

Maybe success can only happen (and be spread) if we restrict access to it.

Maybe the world needs a somewhat isolated ‘system experiment’ that can only remain so (and continue along its special type of development), by restricting access, and therefore be a teaching tool through its successes and short-comings.

Maybe ‘moving away’ from your problems is to not solve them at all and certainly does not lead to overcoming them in-situ.

Maybe those who have the ambition to move away were the ones most likely to effect change and improve their origin, with the move likely resulting in the weakening of the source state and increasing world inequality overall. (is it ethical to allow people to emigrate if that depopulation damages the future potential of the source system itself?)

What I like about this argument is that it seems to accept a utilitarian-universalist meta-ethics, and then argues, or at least tries to suggest (“Maybe…”), that migration restrictions (perhaps even ones as draconian as the status quo?) might serve the common good of mankind through the good example that rich countries can set when they segregate themselves from the rest of the world. I find it wildly implausible that migration restrictions anything like as tight as those the West currently has in place are optimal for the welfare of mankind, and even if they were, I’d have human rights objections. Thus, even if preventing “brain drain” from poor countries did aid development there (on balance), I’d still object to forcing, say, Malawian doctors to stay in Malawi, on the same grounds that I’d object to seizing American doctors by force and exiling them to Malawi. I believe in human rights. But if we could establish consensus that utilitarian-universalism (with deontological side-constraints) is the right meta-ethical framework in which to consider the question, that’s a large point gained.

Finally, thanks to John Lee’s OBAG link, I noticed that my “billion immigrants” scenario got linked in a National Review piece by Mark Krikorian entitled “Where There is No Border, the Nations Perish.” Here’s the context:

But the publics of Europe’s various nations aren’t going to tolerate unlimited flows. The diminution of sovereignty engineered by the EU is bad enough for some share of the population, but many more will object to extinguishing their national existence à la Camp of the Saints. (And “extinguishing” is the right word; just read this piece by an open-borders supporter on how U.S. society would change if 1 billion immigrants moved here.)

Krikorian cites my scenario as evidence (almost, flatteringly if unwarrantedly, as proof) that “the nations perish” under open borders, a phrase amenable to multiple interpretations. It is tendentious because the word “perish” might subliminally suggest some sort of threat of genocide. But if it is interpreted simply as “open borders will bring to a close the episode in world history, which began around the mid-19th century, when the nation-state was the predominant form of political organization,” then I’d tentatively agree. Krikorian disapproves, I approve.

In general, it seems that my “billion immigrants” scenario has made me a useful “reluctant expert” for immigration critics to cite. Maybe that should distress me more than it does. I tend to think the strength of the arguments for open borders is so superior that the more we can get a hearing, even if initially an unfavorable one, the better. Many people don’t even know that being an open borders supporter is a live option. If they’re made aware that one can support open borders, they’ll pay more attention to the arguments for and against. On the plane of intellectual argument, open borders advocates have many rhetorical handicaps, but enjoy the long-term structural advantage of being right.

*My use of the term “meta-ethics” is slightly unconventional. For me, utilitarianism, for example, is a “meta-ethical” perspective.

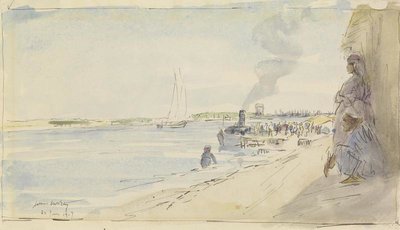

The image featured at the top of this post is a 1917 painting depicting Armenian refugees at Port Said, Egypt.

Related reading

Now, I think this argument does make logical sense and is a pretty decent framework for thinking about foreign policy. If one nation wrongs another, it seems intuitive that reparations should be on the table.

Now, I think this argument does make logical sense and is a pretty decent framework for thinking about foreign policy. If one nation wrongs another, it seems intuitive that reparations should be on the table.