The American city of Detroit is in terrible shape. An online piece in The New York Times by Joseph Stiglitz summarizes its ills: “… 40 percent of streetlights were not working this spring, tens of thousands of buildings are abandoned, schools have closed and the population declined 25 percent in the last decade alone. The violent crime rate last year was the highest of any big city. In 1950, when Detroit’s population was 1.85 million, there were 296,000 manufacturing jobs in the city; as of 2011, with a population of just over 700,000, there were fewer than 27,000.” The city government filed for bankruptcy in July.

Witold Rybczynski of the University of Pennsylvania has described the negative impact of depopulation on cities: “When a city loses population, it loses residents, but keeps the same amount of infrastructure. The same streets must be policed and maintained, the same streetlights repaired, the same water and sewer systems operated, the same transit systems run. It is like an (impoverished) elderly couple having to keep up a large house after all the kids have grown up and moved out. This imbalance has several deleterious effects. Because the city has fewer taxpayers, the quality of its municipal services goes down. For example, police response time to 911 calls in Detroit is currently said to be 58 minutes. It expends scarce resources on nonproductive uses; Philadelphia pays $20 million a year just to maintain 40,000 vacant properties. Moreover, because urban vitality depends on density, without an adequate concentration of people, corner stores close, streets become empty — and dangerous — and abandoned buildings become haunts for criminal activities. According to a 1973 study by the Department of Housing and Urban Development, the tipping point in a community occurs when only 3 percent to 6 percent of properties are blighted; many neighborhoods of shrinking cities passed that point decades ago.”

Mr. Rybczynski, like Detroit’s outgoing mayor, advocates “planned shrinkage” of Detroit. Declaring that “Detroit has no other realistic option,” he suppports “consolidation,” in which people living in underpopulated areas of the city move to other parts of the city. City services to the abandoned areas are then discontinued. Mr. Rybczynski states that “Experience has shown that voluntary displacement of residents is unlikely to succeed, and some version of eminent domain with regard to nonviable neighborhoods is required.”

In contrast, others have offered immigration as a solution to Detroit’s problems. Michael Bloomberg, New York City’s outgoing mayor, has stated that “if I were the federal government… Assuming you could wave a magic wand and pull everybody together, you pass a law letting immigrants come in as long as they agree to go to Detroit and live there for five or ten years, start businesses, take jobs, whatever. You would populate Detroit overnight because half the world wants to come here… You can use something like immigration policy – at no cost to the federal government – to fix a lot of the problems that we have.” Similarly, the Boston Globe’s Leon Neyfakh calls attention to proposals for “…‘regional visas’ that would open up additional slots for newcomers but limit them to specific destinations within the United States, while giving state and local officials a role in deciding how many immigrants—and which ones—to let in. Under this system, states that want to attract more foreign workers could do so, and perhaps even target people with the kinds of skills and training that local businesses are looking for… many parts of the country–especially depopulated cities like Detroit, Cleveland, and Pittsburgh–would love to welcome motivated new residents.” (John Lee has noted that Canada allows its provinces to issue immigrant visas.)

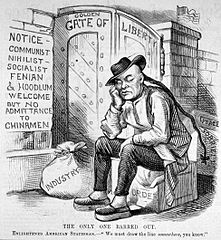

In fact, in Detroit and other depopulated cities, there are currently active efforts to attract immigrants. Organizations in Detroit, Cleveland, and St. Louis are seeking immigrants to help their economies. For example, the non-profit Global Cleveland focuses “on regional economic development through actively attracting and retaining newcomers (defined as ‘immigrants and international and domestic individuals’)…” The goal of the St. Louis Mosaic Project is to have “the fastest immigration growth of any big city in the U.S. by 2020.” In Dayton, Ohio, the city itself “… voted to make the city “immigrant friendly,” with programs to attract newcomers and encourage those already here, as a way to help stem job losses and a drop in population.” (These efforts recall similar ones in 19th century America. Maldwyn Jones, in American Immigration, notes that “After 1865… practically every northwestern state and territory from Wisconsin to Oregon embarked upon a policy of encouraging immigration.” (p. 188) Mr. Jones explains that states sought immigrants because “… they were anxious to dispose of their unsold lands, and they recognized that increased population was essential to material growth.” (p. 187))

There is evidence to support the efforts of these local entities and those who propose regional visas. The key findings of the recently released report “Immigration and the Revival of American Cities” are that immigrants create and preserve manufacturing jobs, increase housing wealth, and make the areas they populate more attractive to U.S. citizens, who follow in response. (pp. 2-3) The study “shows that immigrants are more than just our neighbors; they’re a key part of the way local areas grow and thrive.” (p. 3) Likewise, in his report “The Economic Impact of Immigration on St. Louis,” Jack Strauss of St. Louis University concludes that “there is one clear and specific way to simultaneously redress the region’s population stagnation, output slump, tepid employment growth, housing weakness and deficit in entrepreneurship – Immigration. This report provides considerable economic evidence and statistical analysis using U.S. Census data that increasing immigration will significantly raise employment and income growth as well as boost real wages in the St. Louis region. An influx of foreign-born could reverse the region’s housing prices declines and lower unemployment rates for both whites and African Americans in our region.” (p. 3) (In a previous post of mine, Mr. Strauss’s research showing the positive impact of Latino immigration on African Americans was noted) In Dayton, immigrants have “have started restaurants and shops, as well as trucking companies to ferry equipment for a nearby Air Force base. And they have used their savings to refurbish houses in north Dayton, where Turkish leaders estimated that they had invested $30 million so far, including real estate, materials purchases and the value of their labor.”

Adding a regional visa category to the current immigration system would allow additional people to legally immigrate to the United States. Moreover, they would enter communities where many would welcome them. However, from an open borders advocate’s perspective, there are downsides to a regional visa category. First, it would be limited numerically. Second, it would limit the freedom of immigrants to live where they want during the period of regional residency that probably would be required under the visas.

But would open borders provide the immigrants Detroit and other depopulated cities need for revival? It is conceivable that even with increased immigration flows under an open borders policy, newcomers would go to areas of the country which are thriving, bypassing Detroit and similar cities; open borders doesn’t offer the control over immigrants‘ destinations as a regional visa program would. However, there are factors that would lead at least some of the flow to Detroit and similar cities. First, of course, is the increased flow itself. If only a small portion of new immigrants went to these cities, their immigrant populations could be boosted substantially. Second, there are the aforementioned functioning compaigns to attract immigrants to these localities. Third, these areas may attract immigrants by offering a lower cost of living than more successful cities.

If needy cities didn’t receive enough immigrants under open borders, the federal government could provide additional incentives. These might include an accelerated path to citizenship (based on an idea from Mr. Bloomberg) for immigrants who live in these cities for a certain number of years and, should an open borders system be established involving surtaxes on immigrants’ wages, relief from these taxes for immigrants while they reside in these areas. (Unlike under a regional visa system, failure to comply with residency requirements would mean not deportation but a longer path to citizenship and/or higher taxes. Immigrants would be free to move to a different part of the country at any time.) Local, state, and/or federal governments could also arrange for newcomers, whether immigrants or American-born, to take possession of abandoned housing on the condition that they restore such housing.

Another consideration is that, by supplying a larger supply of immigrants, an open borders policy would prevent a situation in which localities compete with each other to attract people from relatively small pool of immigrants (those already in the U.S., the limited number of immigrants allowed in through the current system, and, potentially, a number of regional visa immigrants). There would be enough immigrants to revive ailing communities throughout the country.

With open borders Detroit and other cities can be revitalized without having to compromise the freedom of immigrants to choose where they want to live, without localities having to compete over a small number of immigrants, and without adding a new layer of rules for regional visas on the current labyrinthine immigration legal system. At the same time, the enthusiasm in these cities for attracting immigrants as a tool for urban renewal aids the open borders cause. Open borders will be attained not only through rigorous ethical arguments but also through a recognition by the native-born population that immigration is not a threat but an opportunity.