I sometimes get the sense that the open borders topic is a bit tapped out, because open borders advocates are so vastly superior to the most vocal immigration restrictionists in the quality of their arguments that it’s hard to have a conversation. Restrictionists can win public debates easily because they have a vast weight of status quo bias on their side. And it’s true that most casual friends of open borders just don’t appreciate how radical the policy is, so a half-decent restrictionist can move the debate in his direction just by explaining that. But when it comes to the big pro-open borders arguments, about how this is the best way to alleviate world poverty, expand economic opportunity and advance freedom for mankind, restrictionists not only don’t have answers to these, they don’t even really understand them. You rarely hear anything from the other side that should really make you stop to think, or question your position. You never find yourself thinking, “Hmm, why is that wrong?” Instead, you find yourself thinking, “What rhetoric will help me make the overwhelming reasons why that’s wrong clear and compelling to the average man-on-the-street who hasn’t thought about the issue, is massively misinformed about the facts, and whose prejudices go the wrong way?” That gets tedious after a while. One just doesn’t learn much that way.

So I thought it might be worthwhile to acknowledge and respond to the article “Immigration, Yes– and No,” by Gene Callahan, at The American Conservative, which is unusually high-quality on the restrictionist side, and shows some awareness of open borders arguments. As usual when I read restrictionist writings (which I usually don’t), I wanted to interrupt the guy with objections at almost every paragraph, but I still came away respecting him and feeling like he was actually worth talking to. He starts by arguing that the Roman Empire was overwhelmed, not so much by “invading” as by “immigrating” barbarians, and that “if Rome had adopted open borders… the Western Empire would’ve been overwhelmed earlier,” because it wouldn’t have had time to assimilate the incoming barbarians. Well, I’ve written about this before. Rome probably made a mistake in letting the Visigoths immigrate as a political entity, but not only did peaceful individual immigrants never cause any trouble for Rome, the last great defender of Rome, Stilicho, seems to have been a German, as were many of his troops. As I put it before, “it looks like Rome fell because nativist know-nothings murdered a talented immigrant general who, with his immigrant troops, was doing the jobs Romans wouldn’t do, namely, defend Rome.”

The author positions himself as immigration “trimmer,” i.e., a moderate who does want some immigration, and he writes that

As a student of Aristotle—hardly a man without principles—I generally suspect that extreme views are expressions of vice and that the path of virtue will involve holding to a course between their hazards.

I, too, consider myself a moderate supporter of open borders, inasmuch as I advocate taxing rather than restricting migration, and using the proceeds of migration taxes to protect the living standards of natives. So we’re both “moderates” if you gerrymander the spectrum in the right way, and of course, this is all rather silly. The problem with being compulsively “moderate” is that you make yourself a slave to whatever the distribution of opinion happens to be at any given time. A moderate in the 1840s might have said that slaves should be treated humanely, but that abolitionism was an “extreme view” and an “expression of vice.” A moderate in mid-1930s Germany might have said that the Jewish world-conspiracy isn’t as bad as extreme anti-Semites suggest, and to contain it, it’s sufficient to restrict Jews’ participation in national life and encourage them to emigrate. The extreme position today may be moderate in twenty years, and vice versa, as public opinion shifts. If you care about truth, you have to be less of a slave to fashion than the compulsive moderate, by definition, has to be. (Thomas Paine had an interesting take: “moderation in temper is always a virtue, but moderation in principle is always a vice.” Ayn Rand’s attack on compulsive moderates is also wise.)

The author writes that most immigrants seek “a better standard of living” and that “such a universal human aspiration surely should not be condemned.” Moreover, “there is little hard evidence that the troubles of lower- and middle-class America in recent years have been caused to any great extent by immigration.” Then he says:

But these economic facts are true in a world with controlled immigration. Would they still hold in a world of open borders?

A good question, and one that open borders advocates sometimes fail to ask. I have always thought that while immigration hasn’t reduced rich-world wages much if at all so far, open borders would reduce the wages of unskilled workers, probably a lot. He predicts that under open borders, “the equilibrium position we would expect is that immigration would continue until the wage differential between American workers and developing world workers disappeared,” which I think is true to a first approximation, though the big question is how much of the equilibration would come from poor-country wages going up, and how much from rich-country (unskilled) wages going down. He adds that “Franklin Roosevelt, hardly a hero to libertarian advocates of open borders, was elected in a large part because of the votes of immigrants or their sons and daughters,” but (a) it is well understood by open borders advocates that immigration can’t (and needn’t) automatically include the right to vote, and (b) a more obvious point to make about FDR is that he was elected shortly after the US closed its borders to most immigration. As long as the club was open to new members, membership was relatively thin in its duties and privileges. The early-20th century progressive movement closed the club and increased the duties and privileges. That’s what we want to reverse.

Callahan points out that immigration has a cultural impact, and that assimilation goes both ways: natives influence immigrants, and vice versa. He writes:

European emigration to the New World is an instructive case in point: if Native Americans had been able to limit the flow of European immigrants, they might have been able to preserve their land and cultures. But, lacking the idea of territorial sovereignty, they could only deal with these immigrants through unconditional welcome or violence. When violence failed, their culture was overwhelmed, and it has largely disappeared. If we value our own culture, we might not want this to happen to it.

But here, several points need to be made. First, if assimilation is a two-way street, the traffic is very lop-sided. Natives influence immigrants far more than the other way around, resulting in a phenomenon called the “founder effect,” where the people who found a society overwhelmingly determine the nature of that society. Case in point: Americans collectively have almost as much German as British blood in their veins, as a result of mass immigration in the 19th century. But US institutions aren’t some kind of weighted average of German and British institutions. They’re just British, plus native evolutions and adaptations. The same goes for culture to a slightly lesser extent.

Second, some cultures are just more advanced and potent than others. If Europeans had never settled the Americas, Native American ways of life would still have been transformed beyond recognition by the cultural products and technologies Europe had to offer. Native Americans would have seen that Europeans had truer beliefs (e.g. in the natural sciences and economics), better ways of doing things, and more beautiful art and literature than they did. Since the mid-20th century, the physical emigration of Westerners to the rest of the world has largely ceased or gone into reverse, but the tsunami of Western cultural, ideological, technological, and economic influence has hardly abated at all. Open borders would not put American culture in jeopardy. If we’re assimilating the rest of the world even when we largely block them from coming, this would only accelerate if they could come here and get assimilated at close range. Probably there would be some influence in the other direction, too, most of it innocuous or beneficial. After all, culture is largely chosen, and for the most part, one doesn’t have to listen to the music or eat the food the immigrants bring with them unless one likes it.

Third, culture is dynamic, and doesn’t remain in stasis from generation to generation just because you hold the gene pool constant. The Sexual Revolution has, since the 1960s, radically altered Americans’ social behavior and family structures. This had nothing to do with immigration, it was a purely native development. Europeans largely abandoned Christianity in the course of the 20th century. That had nothing to do with immigration, either.

Indeed– fourth– immigrants may help to stabilize a culture by choosing it and assimilating to it. American culture seems to have been rather more stable in the 19th century than in the 20th century. At any rate, commitments to traditional family values and small government and Christianity seemed more like constants of American national life, then, whereas in 20th century America, the center could no longer hold, as repeated cultural revolutions swept aside traditional values and ways of life. It may be plausibly suggested that this was partly a result of the closing of America’s borders in the 1920s. Immigrants came here for relatively consistent reasons– to work hard, to practice their religions freely, to enjoy political freedom– and they helped to dilute the flux of generational fashions.

Callahan writes that “if we really value cultural diversity, there is no substitute for these diverse cultures flourishing in their native soil,” but, first of all, I don’t really value “cultural diversity” as such. It depends on the content of culture: whether the beliefs are true, whether the cuisine is tasty and nutritious, whether the customs are just and conducive to happiness, whether the art is beautiful and edifying. If not, let assimilation erase it. If so– second– there’s a good chance that it can hold its own in the cultural marketplace. Irish culture is a case in point, for mass emigration in the 19th century made Ireland a kind of global cultural powerhouse in a way it couldn’t have been if closed borders had prevailed then. Irish folk music really is beautiful and fun to listen to, so I’m glad that 19th-century open borders made it part of the heritage of mankind as a whole, and not just the Irish.

Next, ethics. Ethics tends to be a forte of open borders advocates and a weak point of restrictionists, who just don’t think clearly about it. There’s an interesting question about causation here: do restrictionists avoid clear thinking about ethics because it would lead to unwelcome conclusions, or do people become restrictionists because they can’t think clearly about ethics? Anyway, since one always has to grade restrictionists’ ethical reasoning on a curve, I was very impressed by this statement of Callahan’s:

The last of the issues on immigration is moral: given the modern consensus that no person counts for more than another one in ethical reasoning, can restrictions on immigration—which seem to privilege the existing inhabitants of a polity at the expense of those currently outside it—possibly be justified?

Yes! Good question! Of course, Callahan goes on to say that yes, they can, but that he can even get as far as stating the issue thus is a great leap forward for the restrictionist side. May it be a harbinger of more clear thinking and ethical seriousness on the restrictionist side in the years to come! And I think that we open borders advocates can take a little credit for this advance in the ethical education of the restrictionists. Gene Callahan has read Caplan and quotes him. I don’t know whether he’s read Open Borders: The Case or not, but if he’s familiar with Caplan’s writing, he probably has at least some inkling that Caplan’s not a lone voice in the wilderness, but a spokesman for a cause with a set of enthusiastic adherents.

In his answer to his own question, Callahan seems to be groping towards my argument for universal altruism plus division of labor. He argues that “we, as agents situated in a particular place and time, can… justifiably give more weight to how our acts will affect those nearer and dearer to us than those more distant,” and cites Hayek for the insight that “each actor is best situated to evaluate his own ‘particular circumstances of time and place.'” Yes. We shouldn’t ultimately accept any ethical calculus that places unequal values on human beings, or that segregates humanity into alienated groups with no obligation to care for each other. But the most effective ways for us to take care of each other will involve much division of labor, and within that framework, special obligations to kin and co-members of other natural groupings of people, including cities, churches, nations, etc., are a legitimate factor to consider.

It’s true, as Callahan says, that…

I am much more likely to be successful in my effort to help my next-door neighbor than I am likely to be in trying to help a homeless person in Latvia, because I can personally evaluate my neighbor’s circumstances, while I have little idea what are the real problems plaguing the Latvian indigent.

… but if the Latvian is trying to immigrate to the US, he’s not asking for help, merely that we do not use force to compel him to stay in a country he wants to leave. Our limited knowledge about the “real problems plaguing the Latvian indigent” is a good reason to be wary of taxpayer-funded foreign aid schemes to help him (though I’m not that much of a foreign aid skeptic myself), but can it seriously be suggested that ignorance of his circumstances justifies the use of force to keep him at home? Possibly we would be justified in forcing him to stay at home if we were extremely well-acquainted with his circumstances and knew for a fact that, unbeknownst to him, emigrating to the US would lead him to disaster. Ignorance of his circumstances is surely a reason to rely on his judgment in the matter and let him do as he likes, without getting in his way.

By articulating sound ethical views, then, Callahan has put himself on a train that leads straight to open borders. How does he get off it? Here I didn’t quite succeed in understanding him. He quotes Bryan Caplan saying that “Third World exile is not a morally permissible response” to immigration, and finds it “bizarre” that people who stay put are referred to as “exiled.” Of course, restrictions usually involve deportation, for which the term “exile” is quite apt. And actually, I think “exile” might be a pretty good description of the state of someone who wants badly to live in America and is forced to live elsewhere, even if they were born there, especially if the person has been somewhat culturally assimilated by English, democratic principles, and the whole American cultural package, and is an ethnic or religious minority in the country where they were born. Be that as it may, the Caplan-baiting seems disconnected from Callahan’s main argument. We can concede the semantic quibble, but that doesn’t get us any closer to having a good reason to force foreigners to stay abroad.

Callahan then tries an analogy:

If, after a ship capsizes, we find ourselves on a lifeboat, surrounded by victims flailing in the water, we should save as many of them as we can. But how many is that? Only so many as will not capsize our own boat, a result that would help no one.

Er, okay… but what is the analog of capsizing one’s own boat? Yes, if open borders would lead to a complete societal collapse in the US or other rich countries, such that even the immigrants themselves would be worse off than under the status quo, that would be a strong reason not to open borders. My position is not that we must open the borders even at the cost of a complete societal collapse. My position is that while open borders are indeed a radical policy, and would massively change the US and other rich countries, complete societal collapse is an unlikely outcome even if open borders were implemented in the most reckless and ill-conceived way, and the likelihood of such a dire outcome is negligible if open borders are implemented wisely. There might be some serious negatives, such as a sharp fall in the wages of tens of millions of US-born workers, or a rise in crime. There would be some drastic apparent negatives, such as far more visible poverty in the US, as immigrants would find better lives in the US than they would have had at home, but still shockingly deprived compared to what the US-born are accustomed to seeing. There would also be some drastic positives: world GDP might double, world poverty would be greatly reduced, a lot of people would be able to practice their religions freely who now face persecution, democracies and liberal countries would be empowered in international affairs vis-a-vis autocracies and tyrannies, technological progress would accelerate. The balance of these effects would be positive and very large. If I am right about all this, would Callahan change his mind? Are we in agreement about the ethics, and simply arguing the facts here?

Callahan’s position really does seem to be rather moderate, and I was quite surprised to see the following paragraph, considering that the publication we’re talking about is The American Conservative:

The immigration trimmer is thus likely to reject the most extreme proposals of the anti-immigration camp: giant border fences and frequent requests by law enforcement officials to “show me your papers” are threats to the freedom of every American. Here we see a practical complement to our moral case for allowing as much immigration as we can bear: not only is it right to help the less well-off when we can do so with little harm to ourselves, but it turns out to be very costly, in terms of both physical resources and lost civil liberties, to reduce immigration. Therefore, we should not try to do so until the number of immigrants becomes a serious problem.

I think this places Callahan somewhat to the left of the status quo, which is very encouraging. It confirms my casual impression from years of debating immigration, namely, that in arguing against you, restrictionists tend to position themselves a lot further in the right (i.e., pro-immigration) direction than it seems likely they would have gone without your provocation. If we could establish consensus about “the moral case for allowing as much immigration as we can bear,” that would be major progress. It’s not a very well-defined criterion, and restrictionists would doubtless seek to define the “we can bear” clause in very limiting ways. Open borders advocates would explain why it’s unreasonable to call a large population of resident non-voters, or a significant drop in the wages of unskilled natives, “unbearable.”

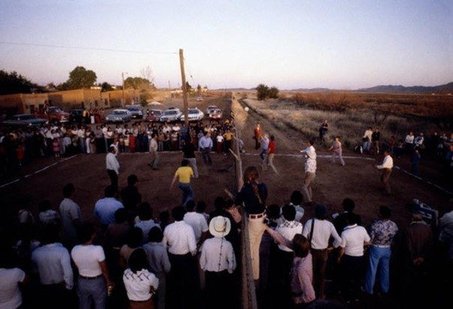

The photograph featured in the header of this post is of Americans and Mexicans playing volleyball over the border, circa 1979. Via RealClear.

Wow, this was so patronising.

Yes, it was like he really paid no attention to what I wrote and just reeled out a pat set of pre-canned arguments.