In 1998, Robert Olsen successfully sued the US State Department, winning his claim that he had been fired for refusing to enforce racist and arbitrary immigration policies. The full judgment in Olsen v. Albright is worth reading. Olsen, who was stationed in Sao Paulo, was a law graduate working as a consular officer reviewing visa applications. He was troubled by the consulate’s policy. The Sao Paulo consulate’s visa manual explicitly documented common abbreviations used when documenting visa refusals, such as these gems:

- LP = looks poor

- LR = looks rough

- TP = talks poor

Note that these determinations were not made on the basis of actual evidence, such as affidavits, bank statements, or letters. They were made simply on the basis of a consular officer deciding the applicant “looked poor” or “talked poor”. Imagine being denied your driver’s licence because the bureaucrat at the DMV felt that you just “look” like a bad driver. Here are some actual, documented reasons for visa denials:

- “Slimy looking[;] wears jacket on shoulders w/ earring”

- “LP!!!!!!”

- “Look Really Poor”

- “Bad Appearance. Talks POOR”

- “Looks + talks poor.”

Of course, if we’re turning down applications because of arbitrary things like someone’s physical appearance, it’s a short hop and a skip to turning them down because of race. The Sao Paulo visa manual further singled out various races and nationalities as especially suspect (ostensibly because of fraud). The manual explicitly states: “Visas are rarely issued to [Koreans and Chinese] unless they have had previous visas and are older.” One would assume that if fraud were the reason, the manual should have laid out ways to corroborate suspicion of fraud, instead of making blanket assumptions about people of a particular nationality or ethnic descent. Instead of providing any such guidance, Olsen’s superiors scolded him for issuing too many visas to people who fit certain unspecified “fraudulent” profiles, and arbitrarily demanded that he double his visa rejection rate from 15% to 30%. Judge Stanley Sporkin eventually found in Olsen’s favour, ruling (emphasis added):

The Consulate’s policies instruct visa officers to view members of these groups as far more suspicious and dishonest than applicants of other races and nationalities. In effect, the manual places a heavy additional burden on applicants of particular nationalities and races that other individuals do not have to face. Based on generalized stereotypes about their behavior, Koreans, Chinese, and Arabs are singled out and stamped with the ignominious badge of “major fraud” before any facts about them are known.

…Although the Court understands the difficulty of the Consulate’s task, greater efficiency is not a sufficient reason to justify the discrimination of people based upon their skin color or national origin. …The Court is aware of the State Department’s difficult responsibilities in adjudicating visa applications under strict time constraints. However, the Court is confident that the State Department can dispatch its duties effectively without using generalizations based on national origin. This nation’s officials once deemed it necessary to make the broad generalization that American citizens of Japanese origin were inherently suspect and likely to commit espionage.

Sporkin noted that Olsen’s superiors did not cite any actual instances of fraud in their evaluation of his performance; they merely demanded he arbitrarily reject more people who they viewed as inherently more susceptible to fraud: “the administrative record reveals numerous instances where Plaintiff’s superiors, in instructing Plaintiff how he should improve his performance, told him to rely more heavily on the profiles.” When Olsen was posted to a different consulate without Sao Paulo’s discriminatory policies, he received an exemplary performance review which noted he “appeared to apply consistency and good judgment to each visa case.”

Sadly, Sporkin’s decision did nothing for the hundreds of people refused visas for being born into the wrong race, or wearing the wrong clothes. Even more sadly, the New York Times noted at the time that “similar policies are in effect at American visa offices around the world.” And this was in a pre-9/11 world; it is a truth universally acknowledged that US visa policy has become even stricter since then. And US consular officers’ discretion has not shrunk: they remain empowered to use virtually any reason they like to deny you a non-immigrant visa, and they strongly oppose the establishment of any rules- or principles-based process, especially one that the public might rely on, citing fraud concerns.

We know that power corrupts, and absolute power corrupts absolutely. As immigration lawyer Angelo Paparelli notes, US consular officers literally have the final say on who gets a visa: it is a decision not even the President can overturn. One immigration lawyer has a heartrending tale of how the absence of any appeals process destroyed her client’s life. Another immigration law blog from Thailand puts it more bluntly: “Many people mistakenly believe that legal concepts such as due process apply to matters going before US Consular officers.” The end result: a US visa policy that denies you a visa simply because you “Look Really Poor.”

The scary thing is, we have no idea how many such cases like these there are. The only reason this matter became public and went before the courts is because of the following chain of events:

- The Sao Paulo consulate explicitly documented their racist and arbitrary visa policies

- Olsen was stationed in Sao Paulo

- Olsen had the moral courage to refuse to apply racist and arbitrary visa policies

- State fired Olsen for his courageous stance

- Olsen sued State for wrongful termination, and did not accept a private settlement

If any one of those had not happened, we would never have heard about this. Under US law, consular decisions are not subject to judicial review, and there is no appeals process. The racist and arbitrary nature of visa policy only came before the court because it was at issue in Olsen’s allegation of wrongful termination — not because the court was reviewing visa policy or specific visa denials, something the court had absolutely no legal right to do.

There is literally more due process and transparency involved in applying for a US government secret security clearance than there is in applying for a tourist or student visa. Anyone who has their clearance application denied is allowed to appeal, and the findings of these hearings are documented and made public. Until the courts told the US government that they were simply going too far, immigrants were not even allowed to see the evidence that the US government had used in deciding to deny their visa. The US government’s position until 2011 literally was:

- Appeals against denied security clearances are public matters, and the evidence behind the government’s decision needs to be public by default

- Appeals against denied visas are a threat to national security, and the government should not make public any evidence without undergoing the tortuous Freedom of Information Act process

The people whose visas were denied by the Sao Paulo consulate are in all likelihood the tip of the iceberg. Because there is no appeals process and the US government hides the visa adjudication and decision-making processes behind a veil of “national security” that doesn’t even apply to top secret security clearances, we have no way of knowing how many other US consular outposts might be enforcing similarly arbitrary or racist policies. Considering the opacity and dictatorial discretion here, it would be surprising if Sao Paulo was the only one. Every year, 1 to 2 million people are denied US visas for no real reason — they’ve passed criminal background checks, they’ve passed medical checks — the consular officer reviewing their application just felt like turning them down.

The victims of racist and arbitrary immigration policies here are not just immigrants — people who want to be with their friends and family, people who want to earn an honest living. They are also people who simply wanted to visit or study in the US. They had family they needed to see, places they wanted to visit, business partners they needed to meet, classes they needed to attend. And all because they “Look Really Poor” — not because they posed any sort of threat to the US. US policy is that they have no channel for appeal — even if, as one immigration lawyer puts it, “the denial was based on a consular officer’s mistake of fact or a misunderstanding of the law, or even if the officer acted capriciously, arbitrarily, or maliciously”.

Yes, we can improve immigration policy by limiting consular discretion, and guaranteeing more due process. Making the evidence used to deny visas public, and allowing visa denials to be appealed would be a good start. But even these improvements are playing at the margins. We need to abolish immigration policies that assume all foreigners are evil or criminal until they prove conclusively otherwise. As long as we continue to make the assumption that billions of people around the world are guilty until proven innocent, we cannot have any true “due process.” Perhaps the benefits of this manifest injustice outweigh the costs. But there is no evidence, no analysis, truly showing that that is the case. Until you can show me why we should throw fundamental due process protections out the window — why the benefits of making visa decisions in secret behind closed doors, based on arbitrary criteria like race or physical appearance, outweigh the costs — I can only conclude that the immigration policy status quo is an affront to the most basic principles of any civilised justice system.

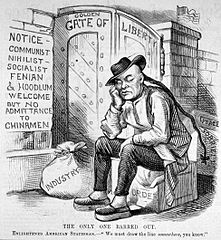

The cartoon featured at the top of this post depicts a Chinese immigrant being refused entry to the United States, and was published in 1882.

3 thoughts on “US visa policy: where everything’s made up, and due process doesn’t matter”