Border controls that prevent innocent foreigners from travelling peacefully are in every meaningful way identical to laws enshrining racial segregation and apartheid. Both aim to exclude people from peaceful participation in civilised society, not because of anything they have done wrong, but purely because of a circumstance of birth that they had no choice over.

Open borders advocates have long compared the modern border regime to apartheid and other forms of racial segregation. But American journalist Stephan Faris has done us one better: in his brief book Homelands: The Case for Open Immigration last year, he outlined exactly why and how we shouldn’t let artificially-drawn borders delude us into thinking our immigration laws don’t somehow constitute an arbitrary form of discrimination comparable to apartheid. Stephan was recently gracious enough to spare some time for an email interview with us, which we’ll be publishing next week.

In the mean time, I’d strongly urge you to head over to Amazon and buy the book; it’s currently listed for under 3 US dollars, and is only thirty pages. I finished the book in one sitting, and felt I got far more than my money’s worth. The intro blurb from the publisher:

As a child, Stephan Faris nearly failed to qualify for any country’s passport. Now, in a story that moves from South Africa to Italy to the United States, he looks at the arbitrariness of nationality. Framed by Faris’s meeting with a young orphan as a reporter in Liberia and their reencounter years later in Minnesota, Homelands makes the case for a complete rethinking of immigration policy. In a world where we’ve globalized capital, culture, and communications, are restrictions on the movement of people still morally tenable?

I’d say the book delivers on these claims. But rather than take my word for it, why not preview an excerpt and judge for yourself? Deca, the publisher of Homelands, has allowed us to publish an edited excerpt of the book — one that doesn’t give you the full colour of Stephan’s stories or arguments, but should whet your appetite for the full-length item:

After some 250 years of nationalism, the segregation of the world’s population into separate countries seems as natural as the division of the globe into continents. So it’s important to remember that restricting immigration is a political choice, one whose burden is carried largely by the less fortunate.

Joseph Carens, the philosopher, is right to describe nationality as a birthright reminiscent of medieval feudalism. But as I discovered during my time in Africa, you needn’t go back as far as the Middle Ages to find an unsettling analog to our closed borders. If I’ve come to the conclusion that our immigration policies are one of the great moral challenges of our time, it’s in part because they very much resemble one of the most clear-cut acts of injustice in recent history: an attempt by South Africa’s apartheid regime to preserve racial privileges in the face of worldwide opposition.

Apartheid was clearly becoming untenable, but they couldn’t contemplate giving up white privilege. So they settled on a different solution, one that would abolish overt discrimination but still allow them to retain their grip on social, economic, and political power: a partition of South Africa modeled explicitly on existing national borders, with the nation divided into rich and poor countries.

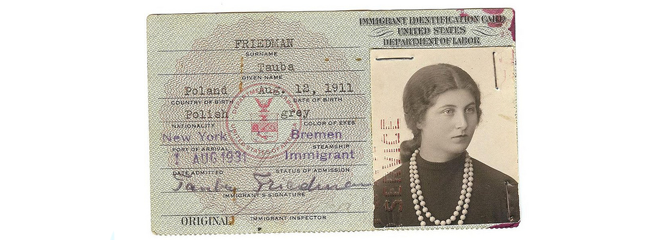

South Africa had already set aside land for the native population. Thirteen percent of the country was designated as native reserves, known as “homelands,” where black Africans had to live unless they could prove they were working for a white employer. Movement in and out of these homelands was restricted. The Pass Laws required nonwhite citizens to carry “passbooks” with their name, address, and photograph or risk imprisonment and expulsion back to the reserves. It didn’t seem like a big leap to go from “homelands” and “passbooks” to “countries” and “passports.”

The idea didn’t seem as crazy then as it might today. In the period after World War II, new countries were erupting out of disintegrating colonial empires all over the globe. The border between India, Pakistan, and what would later become Bangladesh wasn’t drawn until 1947, when a British administrator was given five weeks to decide where the division would run. All across Africa, new nations were hoisting new flags: Ghana in 1957, Guinea the year after. By 1960, the continent had seen the creation of sixteen new independent states, from Somalia to Senegal, from Mali to Madagascar.

At the same time, all around South Africa, new nations were coming into being. The Republic of Botswana, just to the north, elected its first government in 1966. Swaziland, in the east, declared independence from the United Kingdom in 1968. Most remarkable of all was the transformation of the British Protectorate of Basutoland, a tiny landlocked colony completely surrounded by South Africa. In 1966, it pulled down the Union Jack and joined the roster of nations as the Kingdom of Lesotho.

If such a miniscule patch of land could stand alone as an independent country, why not the 13 percent of South African territory set aside as native reserves? “The dream was: how do you get rid of the immorality of apartheid?” said [former South African Minister Roelof Frederik] Botha. “How do you get rid of the reprehensible suppression and racial discrimination? If a sufficient number of black people in their homelands—exactly like Swaziland, like Basutoland, like Botswana—if they could also become independent, then maybe the whites might not feel that much threatened anymore by the overwhelming majority of black people. And apartheid, in its nefarious sense, in its reprehensible sense, could be dismantled.”

“So the idea took root,” he said. “Let us make these nations independent. They can have their own parliaments, their own governments, their own courts, their own judges. Each one must have a capital and a parliament and a president and a prime minister and a cabinet. They will be sovereign, and they will be independent. And then you would have a sort of equality, a constellation of southern African states.”

Blacks could have their independence. But when they came to where the work was, they would have to do so as immigrants. “The problem was reality,” said Botha. “It did not resolve the issue of racial discrimination. So the dream was turned into a nightmare. It was a dream that was not based on reality.”

To be sure, there are differences between the global system of immigration restrictions and South Africa’s attempt to entrench white privilege through the partitioning of its territory. But it should give us pause to think that when the architects of one of history’s most recognized evils set out to codify their system of injustice, they looked at our borders and passports and saw a lot to like. Intentions aside, the biggest difference between the two is that the South Africans wanted to draw the boundaries and assign the nationalities. We make do with the existing ones.

What’s most striking about the story of South African apartheid is how similar it is to our efforts to restrict immigration today. Numerically, the parallels could hardly be more perfect. In 1994, there were six times as many nonwhite South Africans as white South Africans, according to data compiled by Michael Clemens. Whites earned roughly eight times as much as their black or mixed-race peers. Today, there are roughly six times as many people living in low- and middle-income countries as there are in high-income countries. Residents of rich countries typically earn about seven times the average income of the rest of the world. If numbers are anything to go by, ending economic and geographic—not to mention political—segregation in South Africa was a bigger challenge than dropping barriers to immigration would be today.

There are endless practical objections to allowing people to move where they can best profit from their willingness to work. But there were practical objections to ending apartheid as well, and practical objections to ending slavery in the United States. Few would argue that the practical objections outweighed the moral imperatives.

Again, the full 30 pages are worth buying. I think Stephan very concisely sums up the fundamental moral case for open borders, and in a very compelling way. Check back next week for our interview with Stephan!

The image featured at the top of this post is of a man crawling naked through the South African border fence near Beitbridge, Zimbabwe, making his way to South Africa. Originally published in the Cape Times, it was taken by Henk Kruger in 2008, and won the runner-up prize for World Press Photo of the year.